Derek Warwick

NEVER LOOK BACK

- In stock, ready to ship

- Inventory on the way

CHAPTER 7

THE BIG TIME AND THE BIG DROP

Much as I loved Toleman and would have been happy to stay with the team for another season, I became aware in 1983 that other people in the paddock were watching me. Renault had been interested the previous year but had opted for Eddie Cheever, but he’d had a tricky season and I knew there was a chance I could go there for 1984. It was a huge prospect for me, to be part of such a big organisation with a massive budget behind it. I also briefly talked with Frank Williams but don’t remember that being anything serious, because by then I was well down the line with Renault.

By this time, Renault was one of the top three teams. For many years the rules had allowed 1.5-litre engines with forced induction (supercharging or turbocharging) as an alternative to the usual 3-litre normally aspirated engines, but Renault was the first to try this, starting in 1977. Like Toleman, Renault had been a laughing stock initially, because of all the problems that came with developing F1’s first-ever turbocharged engine, like overheating, blowing up, turbo failures and gearbox breakages. Because of all that, Ken Tyrrell christened Renault’s first little car, the RS01, ‘The Yellow Teapot’. Things got a little better in 1978, then Renault won for the first time in 1979, and after that the genie was out of the bottle.

I began discussions with Renault near the end of 1983 and knew that racing for a top factory team with turbo engines was the way to go. Renault was the front-runner that year and Alain Prost was always favourite to win the title, but in the end Nelson Piquet got it for Brabham. Prost won more races, four against three, and finished only two points behind after defeat at Kyalami in the final race.

Then, only two days after Kyalami, Renault fired Prost. In many ways he was made to carry the can for the team’s failure to win the title, but some suggested that there were also underlying problems in the relationship that had influenced the decision. In the weeks that followed, Renault told me they were going to have an all-new driver line-up for 1984. And during this period I learned that Toleman was chasing Ayrton Senna. He’d just won the British Formula 3 Championship and had tested with promising results for Williams, McLaren, Brabham — and Toleman. Apparently, he was quite good.

Before long, it was broadly confirmed that I would be one of Renault’s new drivers, and that Ferrari’s Patrick Tambay would be the other. So it was then a matter of agreeing terms and signing the contract. By F1 standards, I’d been earning peanuts with Toleman. In 1983 my deal was £60,000 for the year, and out of that I’d had to pay most of my expenses, and all sorts of extras like having Heinz Lechner look after my health and fitness.

The negotiations were with Gérard Larrousse, the former racing driver and double Le Mans winner who headed the Renault team. I suppose I left it to Gérard, who was a decent, likable bloke, to outline the terms because, to be honest, I had no idea. I heard rumours in the pitlane about what some drivers were earning and the kind of deals they had, but I was making it up as I went along and didn’t have a manager. All I knew was that I wanted to sign for Renault. But while Gérard might have started the negotiations, I was a good poker player and a very quick learner, so I would bat things back saying that, no, I was looking for this and that, and I wanted to be able to keep my own personal sponsors. He said he would get back to me.

In the meantime, in January I went to the Racing Car Show in London with my three mechanic mates. While we were there, Dad phoned me. We were waiting for a telex from Renault, confirming the full details of my contract.

‘Come on Dad, what?’

‘Just sit down, boy. Sit down.’

‘Never mind that, Dad, what’s going on?’

‘Boy, just sit down. You have to sit down.’

So I sat down. ‘Okay, now what?’

And that was when he said that Gérard had just sent the telex confirming the contract and the amount of money we’d discussed. It was telephone numbers, the Big Time for me. I went from earning tuppence to quite a few quid, let’s put it that way. I could see why Dad wanted me to be sitting down.

My heart was beating like a sledgehammer. ‘What about personal sponsorship?’

‘Yeah, you can have whatever you like across your chest. Wear whatever helmet you like, and you get two sponsors on it.’

I just couldn’t believe it. Gérard had agreed to everything. I already had a personal sponsorship deal with Sergio Tacchini, the Italian sportwear company, regardless of who I drove for.

Right from the start, Renault was a whole different ballgame from Toleman. The way they went about their business was so different. At Toleman I would go in and say ‘hi’ to every single person, and I knew all their names. Now, all of a sudden, I was with this massive team and trying to segregate everybody in blocks so that when I said ‘bonjour’ and shook hands, I’d remember who they were. Of course, that’s tricky when you’re in a new team and there are so many different people. And, understandably, someone would get offended if you greeted them afresh a second time, showing you hadn’t recognised them. Not the best way to get the most out of people, especially if you don’t speak their language. So, the biggest problem for me was to remember whose hands I shook and what their names were. At times I felt confronted by a blizzard of faces.

The French really taught me the etiquette of shaking hands and saying ‘good morning’ every day. I came to love that. It meant so much to everyone in the team. I’ve continued that ever since. Today at my dealership and building companies my people have to say ‘good morning’ and where possible shake hands, because it’s something they know I appreciate and like. And they like it too.

I soon fitted in quite well at Renault because of my commitment. I went to the factory in Viry-Châtillon, about 15 miles south of Paris, many, many times before I first tested the car at Paul Ricard. By going there so regularly, I really got to know the guys at the factory, as well as those in the race team. I knew I had to work hard to gain their respect and trust. Sometimes I would also help on the race cars, and they really appreciated that.

A significant task for me was engine development work in the team’s own engine facility. They had a simulator for testing the engine. It was a ground-breaking thing at the time but, looking back, unbelievably primitive. You were put in this rig outside the partially soundproofed dyno room with a window so you could see the engine on the bench. You sat in a Corbeau seat with a steering wheel, a throttle and a gearshift, and a paper circuit map in front of you. The idea was to ‘drive’ around the general outline of whichever circuit they’d chosen, such as a tight one like Monaco or the open sweeps of Paul Ricard. You had to work your way around the circuit in your head and judge when to go up and down the gears. So, imagine you were going down a long straight in sixth gear close to 200mph with a hairpin ahead. You’d have to go down the gears for the hairpin, turn in, then get the power on again as you went back up the gears, but without the steering wheel, gearshift and throttle being inter-connected with the track map. The controls were connected to the engine, which sat happily screaming away on the other side of the glass, but the rest was all in your imagination, pretending you were following the map. It was very difficult initially, but I got into the rhythm of it. They wanted me to downchange and upchange aggressively so that the engine hit the rev limiter, to give it a good workout. And the big thing, obviously, was not to miss gears, although we did try various things to stress the unit. It really was an extraordinary contraption. I wish I’d taken a photo of it.

So, when I went to Ricard to test the car for the first time, I was already part of the family. The team had its own facility there, two-thirds of the way down the long Mistral straight, with its own pitlane going in and out. That was so cool, just driving straight in and out of our private garage. Every day I spent there I had to pinch myself.

There were times when we were testing almost 24/7 at Ricard and I did so many miles there. At the end of 1984, I was still lapping at noon on Christmas Eve. I remember saying I simply had to get away to fly out of Marseilles and get home in time for Christmas, but they didn’t seem to treat Christmas the same way and kept saying, ‘Just one more run.’ In the end I had to skip off and leave them to it. But that commitment was superb and it was great to know that the Renault guys used literally every single moment.

My first experience of the V6 turbo engine was just sensational. But while it certainly had a lot of power, it also came with a version of the turbo lag that I’d experienced, so balancing the car was difficult at times. You had to compromise the perfect balance against the delay and the arrival of the power was still a bit like a switch, although a gentler switch than on the Toleman.

I also got to know Patrick Tambay during this pre-season phase. Let’s just say that we went out a few times to explore Paris, which was… educational. And fun, as you could imagine. He taught me a lot of things; manners, honesty, how to be a gentleman (maybe he failed there), all the things that make a good person even better, if you like. Years later he told me that he trusted me as a team-mate, and that had been important to him. He needed to trust people. With other drivers, maybe it hadn’t been quite the same. And, in turn, I always knew I could trust him. Sadly, after suffering from Parkinson’s in his later years, Patrick died on December 4th, 2022. I was hugely fond of him. He was one of the loveliest, most trustworthy, genuine racing drivers I ever met.

Right from the start of the season the Renault RE50 had the pace and I really should have won the first race, in Brazil, where I qualified third, my best-ever grid placing. Elio de Angelis put his Lotus-Renault on pole from Michele Alboreto’s Ferrari, but the cars I was concerned about were the McLaren-TAG Porsches, with Alain Prost fourth and Niki Lauda sixth, sandwiching Nigel Mansell in the second Lotus.

Michele burst into the lead on his Goodyears and I was second on our Michelins, although I gradually lost a bit of ground to him. Then Niki, who was also on Michelins, barged quite forcefully past me on the 10th lap, not fully positioned when he came by. Going into the left-hander at the end of the back straight, I held my line to make it awkward for him, and as he moved over he whacked my front suspension. He said later that he didn’t expect me to stay out on the wide line as long as I did, and that his car jumped a little over a bump on the entrance to the final corner as I turned in, but his right-rear wheel hit my left-front. To be honest, it didn’t feel like much of a knock, and we both carried on.

Then on the 12th lap Michele had a brake problem that caused the Ferrari to spin violently and without warning. Niki and I, running first and second, were lucky to avoid it. On lap 24 Alain caught and passed me, then took the lead from Niki on lap 38. As Lauda then slowed with electrical problems, Prost made his pitstop but was delayed by a sticking wheel nut. Suddenly I was in front and seemed to be heading for my first victory. But with 15 laps to go I started to feel a vibration in the front end, and after a while I could see that the left-front wheel wasn’t happy. There was no way I was going to come into the pits at that stage. Then on the 51st lap, with only 10 laps to go, the left-front upper wishbone broke and I spun into retirement.

The one thing I realised while leading those 12 glorious laps was how easy it is to win in a good car. I think that’s why I later loved driving sportscars, because I was always in a winning car. After all the hardship over the years while racing poor cars, it reminded me how it could be. But I wasn’t getting carried away.

In retrospect, maybe I should have given Niki more room early in the race. Although I stayed to the right of the track, perhaps I should have braked earlier and given him the space to go through the corner. I didn’t because I wanted to make it difficult for him, but that awkwardness cost me the race. Looking back, it was probably the nearest I ever came to winning a Grand Prix.

When you lead like that, it gives you confidence, and the team grows with you. Now Renault had more and more certainty that I could do the job. They believed in me. The car was good, the Michelins were very good. I had a good relationship with Michel Têtu, the chief engineer. And good old John Gentry was there as my engineer because I’d brought him from Toleman.

Despite the disappointment in Rio, we all felt things were going in the right direction. For much of the year the RE50 would remain quick. It was magnificent car. Well-engineered, a lot of downforce, a great engine.

But it’s a good job I never look back. When I didn’t win in Brazil, I still thought that my first win would come eventually. Sadly the cards never fell that way, mainly because of unreliability. That opening round in Rio was the nearest I ever came to winning a Grand Prix.

But the next two races also went pretty well.

I was pretty fired up for Kyalami because I was still reeling from the pain of Brazil. In pre-race testing there, our engine people came up with a new turbo set-up for the V6 engine. Normally we had two turbos, one per cylinder bank. But now there were four, two per side, one bigger than the other. It was horribly complicated fitting two turbos each side with all the exhausts and other pipework, but it was clever stuff. The idea was that the smaller turbos would come in early and give instant pick-up, then the larger ones would kick in for greater power higher up the rev range. I tested this in the spare car during Friday practice. It may have been clever stuff but the flipping thing had far more lag than the standard set-up, although the power when the second turbo came on strong was unbelievable, like a rocket. But the car was frankly undriveable because the lag could almost be counted in minutes, so we stuck with the conventional set-up.

Patrick and I enjoyed playing tricks on people within the team. In South Africa we stripped out team manager Jean Sage’s hotel room and set up the furniture outside next to the swimming pool. When he came in that evening, there for everyone to see was his wardrobe, table and bed, with his underwear laid out on the edge of the bed. He didn’t think it was particularly funny… but he got his own back the next day because I came back to find all my clothes actually in the swimming pool. Everybody thought of Renault being a bit starchy but Patrick and I had a lot of fun with them.

At Kyalami, Niki got the win he should have had in Brazil, and Alain was second after starting from the pitlane, indicating just how strong the McLarens were that year. But I was third, albeit a lap down, giving me my first F1 podium. But now that was expected of me, and I expected it of myself. After all, I had one of the best cars. Of course, your first podium is always special, but when you get to that stage of having a terrific car, podiums become the norm.

Early in the race I’d been impressed by the speed of the Williams on the straight with its Honda engine. Although our motor was pretty good, I couldn’t do anything about Keke Rosberg for a long time, and then my plan to run non-stop was thwarted when I needed to pit for fresh rubber on the 38th lap. I had the satisfaction of taking on and passing Michele’s Ferrari on lap 51 after running side by side all the way down the main straight to Crowthorne. He was always a hard but fair driver, but I wasn’t cowed when he tried to squeeze me and I slipped ahead, only to pick up a puncture in the right rear five laps later. That dropped me to sixth but I got my head down again and picked up a place when Jacques Laffite’s Williams retired, then repassed Michele, and finally moved up to third when poor Patrick’s metering unit broke.

As well as being my first podium, something else made it even sweeter. When I looked down at everyone standing on the track in front of it, there were all my mechanics from Toleman, looking up at me and cheering. That bond, that affection and respect, brought a huge lump to my throat.

Remember how, having waited so long for points, I scored them in the last four races in 1983? Well, after waiting for a podium, another one came along straight away, at Zolder in Belgium. And it was a bit of a surprise, to be honest, not just because it proved to be a Goodyear weekend with Michele Alboreto dominating for Ferrari, but because I’d whacked my knee karting with my daughter Marie a few days earlier, bruising it badly. Despite that, I was fastest on Friday. I really screwed everything I could out of the car on race rubber after getting baulked by traffic on my best lap on qualifying tyres. I couldn’t maintain that relative pace on Saturday, even though I actually went faster. Michele was too quick on his Goodyears and his Ferrari team-mate René Arnoux sewed up the other front-row slot. Keke Rosberg also put in a very quick lap with his Williams-Honda, leaving me fourth on the grid. But I was the fastest Michelin runner by a mile.

Michele won the start, and that was pretty much it as far as any battle for the lead was concerned. I got the better of René and ran second until my tyre stop on lap 27, when he and Keke got ahead, but I was back in second by lap 44 and stayed there for the remaining 26 laps. I spent the whole race waiting for that Ferrari #27 to break, but it didn’t. But second, just over 40 seconds behind, was still my best F1 result to that point, and Patrick down in eighth was the next closest Michelin runner. This left me second in the World Championship table, five points behind Prost. That felt pretty good. It was what I’d dreamed of since my F3 days.

I finished again at Imola, fourth and best Michelin man, as Prost won to stretch his lead over me to 11 points. After I’d nursed the RE50 home, I remember getting angry with Gérard Larrousse when he said, ‘Well done, Derek.’ I didn’t think the result was good enough, given the speed of the McLarens, and he and I ended up in a right old shouting match when I said that the whole thing was a disgrace. It worried me that he seemed to think fourth place was good enough. I was aiming for firsts.

I was fighting Nigel Mansell very hard for third at Dijon in the French GP when I went off as we were lapping Marc Surer on the 54th lap. I was right behind Nigel’s Lotus-Renault and got caught out when he braked early. I locked up and slid into and over Marc’s Arrows-Cosworth. It was quite a big one and I was momentarily knocked out. The front suspension also intruded into the monocoque, bruising my right leg. Marshals had to help me out of the car.

Patrick, meanwhile, had started from pole, led a total of 47 laps, and finished seven seconds behind Niki’s winning McLaren. While I might have wished that was me, it was a hugely encouraging display of our potential.

Things started to come a little unglued in Monaco, where I qualified fifth with Patrick sixth. It was raining at the start, and as Prost led Mansell into Ste Dévote, I made a brilliant start and grabbed third right behind them. But then René, who’d started third, slid off the right-hand kerb, hit my car and shoved me into the barrier. Seconds later, Patrick had nowhere to go and smashed into me as well. My Renault broke in half like an egg and I stepped out of the front of it. Patrick sustained a broken fibula because a lower wishbone was pushed into the cockpit just like on my car in Dijon. The worrying thing here was that we’d both crashed at relatively low speed, yet both chassis broke.

Later, I watched as Ayrton Senna passed Prost for the lead, driving the Toleman I’d abandoned, before losing a rightful win because Clerk of the Course Jacky Ickx had red-flagged the race the previous lap so that the result went back one lap. I really felt for the Toleman boys, who thoroughly deserved to have won. It seemed off that a driver who’d been known for his prowess in the rain had halted the race like that.

I was fourth in the World Championship as we headed to North America. I qualified fourth in Montreal and was running fourth behind winner Piquet and the McLarens before the underbody worked loose and forced me out after 57 of the 70 laps. I started sixth in Detroit, stopped early from fourth place for a set of harder-compound tyres, and got back up to a promising third when the gearbox deteriorated and put me out on the 41st lap.

There was a second race in the United States that year, two weeks later, in Dallas. And what a mess that was. It was quite fun being there, including a trip to South Fork, the ranch made famous by the Dallas TV series. We met members of the cast, most notably Linda Gray who played Sue-Ellen Ewing.

The track itself was a nightmare. It wasn’t a bad layout, better than Detroit, but the surface kept breaking up and there were all sorts of arguments with the race organisers. They didn’t seem to have a clue what they were doing. Perhaps that was what persuaded the promoter to disappear afterwards with a lot of the money…

But the worst thing for me was that it was another race I should have won, and this time it was my fault that I lost it. I was fully to blame — and Rhonda didn’t hold back when she said exactly that. She didn’t talk to me for days. Believe me, I didn’t want to talk to myself.

I was sixth quickest on Friday, then fastest on Saturday morning — I was glad that seemed to be becoming a habit — when I went out the moment the track opened and banged in a lap 1.5s faster than anyone else managed. In the end the Goodyear-shod Lotus-Renaults of Mansell and de Angelis took the front row, with me third, one of few to improve in the increased heat of Saturday qualifying.

There were then interminable delays and arguments over the state of the track on race day. The warm-up was scheduled to start so early that Jacques Laffite made everyone laugh by turning up in his pyjamas.

To be honest, I was a little relieved that René Arnoux had a firing-up problem that forced him to start from the back of the grid, and as the Lotuses led away I settled into third place. I soon passed Elio, then set off after Nigel. He was four seconds ahead but I reeled him in quickly, and was really looking forward to proving who was the leading British driver.

Senna had already crashed while chasing me, and Niki, Elio, Keke and Alain weren’t putting me under any pressure. I had the quickest car that day, and the race was there for the taking. I pulled alongside Nigel using my car’s over-boost button and was almost past him when I had to touch the brakes. The car pulled left, locked up the left-front, and slid into the tyre barrier. I should have been a little more patient because the brakes had been pulling from the start. The trouble was they’d been changed before the race and hadn’t been bedded in enough. Normally we would have been able to do that in morning warm-up, but that had been cancelled, and instead we’d only been given three laps immediately before the start of the race.

I was so disappointed. Anyone would be in that sort of situation. One thing I have to say about Dad is that when I occasionally messed up like that, he never said or did anything because he knew I’d be hurting inside. I didn’t need anybody — other than Rhonda! — to say, ‘Well, that was a screw-up, Derek.’ If anyone had said that to me in Dallas, I’d probably have punched them anyway, because I was so angry with myself.

I was like that all the way through my career and never wanted to make excuses for anything. I was always honest with my mechanics, engineers and bosses. When I made errors, I’d say so, and they knew I was always straight with them. I was the same with the journalists. I’d come into the press room and say, ‘Sorry guys, I left two-tenths out there’ or, ‘Sorry guys, I locked up going into Turn 15.’ Or if I’d done a good job, I’d say, ‘That was it, there’s nothing left in that car.’ I always thought there was so much trust between us in the team that if I called our people at midnight and said I’m really not sure about the engine or a gear ratio, they’d get straight up and change it.

When you reflect on that, it’s incredible how people are willing to invest their belief and loyalty in you. For people to do that for you is very humbling. But they knew I wouldn’t ask them to change anything just for the sake of it or so I could fabricate an excuse. They would just do it.

I was desperate to make amends when we got to Brands Hatch for my home race, and thankfully I did. From sixth on the grid, I brought the RE50 home second to Niki’s McLaren, and ahead of Ayrton in the Toleman, benefitting when Prost’s McLaren broke its gearbox and Piquet’s Brabham lost boost. I figured I was owed something. And again I savoured my moment on the podium, not least because I was the leading British driver again.

To be honest, I’d found it a dull race. As I’ve alluded, it’s the easiest thing in the world to run with the leaders in a thoroughly competitive car that’s working well. People said I drove really well to finish second, but it didn’t feel like that to me. There was no way I could make any ground on the McLaren, so I was pacing myself to Senna’s Toleman and Elio’s Lotus, which were next up behind me, but not close enough to cause me any trouble. I didn’t feel I had to work particularly hard for that result.

Poor old Patrick was running fifth when his engine broke spectacularly. Believe it or not, a blade from Nelson’s turbocharger was found embedded in one of his radiators, explaining why both cars struck trouble.

We were quick again at Hockenheim, where I finished third after qualifying in the same position, chasing Prost and Lauda home in the McLarens. But it was just like the previous race at Brands. I ran alone for much of the distance and it all seemed rather boring. Making it a good day for us, Patrick, who’d qualified just 0.04s slower than me, was fifth, behind Mansell.

The engine broke when I was running fifth in Austria. After qualifying fourth in Holland and fighting over sixth with Laffite’s Williams-Honda, I spun off on his oil. Patrick led for a while at Monza, which gave us all a much-needed boost, but then his throttle cable broke. It was another one of those weekends, as my engine blew up when I was running fifth. Overheating took me out of fifth with six laps to go at the Nürburgring. And the last race of the season, in Portugal, did nothing to cheer me up. I started only ninth and spun trying to pass Michele, so I was down in 13th when the gearbox broke.

In many ways we did a good job that year. We were always quick and in with a shout, but unreliability killed us no matter where we were or what we were doing. I only finished five of the 16 races, and four of those were on the podium, with two seconds and two thirds. I could have won twice, possibly three times. I scored 23 points, finished seventh in the standings, and Autocourse ranked me the year’s fourth-best driver. I would love to have 1984 again and push harder on the reliability side of it, but, yes, it was good.

Although Renault really was a fantastic team, in some ways it was just too big. I felt there were too many departments that pulled in different directions, and definitely too many committees. One of the problems was that every department, but especially the engine department in its own separate facility, thought it was the most important, and there was no-one strong enough, not even Gérard Larrousse, to pull them all together. But it was still a great team.

By Brands Hatch in 1984, Gérard was putting me under pressure to sign for another year. He increased his offer several times, to a ridiculous figure. Despite all that, I’d decided I wanted to stay anyway, although I’d been speaking to Williams and had also had a very distant conversation with Marco Piccinini at Ferrari, although that was nothing serious. I was driving for a top manufacturer team, I was earning good money, the car was quick. I had a strong team-mate who’d won two Grands Prix with Ferrari and I was showing up well against him, adding to my credibility within F1.

I also consulted the Three Wise Men who were my confidants at that time: Nigel Roebuck of Autosport, Alan Henry of Motoring News and Maurice Hamilton of The Guardian/The Observer. They were good honest guys who really wanted me to succeed and be in the right car. I trusted them and could tell them things that I wouldn’t tell most other journalists. The three musketeers were good for me. And, of course, I was also talking with Dad and Uncle Stan, and friends. Everyone agreed that staying with Renault was the right thing to do.

People look back and wonder why on earth I did stay considering what happened at Renault in 1985 and what developed for Mansell when he went to Williams. But Renault was the obvious choice at the time, and Williams, apart from Rosberg’s win in Dallas, hadn’t done too well in 1984. The Honda engine had a reputation for delivering its power like ‘The Belgrano’, all or nothing, and the FW09 chassis hadn’t been that good.

I also think that, for Frank, the driver tended to be something just to be plugged in like a light bulb. Of course, there were exceptions: he’d been close to Piers Courage and Alan Jones, and of course he always wanted Ayrton Senna, whom he worshipped. With most drivers, though, that was just the way he ran his team. Over the years, quite a few drivers seemed to fall out with him and leave, sometimes mid-contract or even as World Champion. But if Frank thought you got bigger than the team, you were out. Actually, I’ve always believed that he and I would have got on really well together because we shared a no-bullshit approach and I was always honest.

But, as I keep saying, I never look back. What’s the point? I made my decision, without the benefit of a crystal ball. Based on what had happened in 1984, staying with Renault was the right thing to do.

So, should we have had better reliability? Yes, absolutely. Did we not meet expectations? No, we didn’t. But I’ve always been a believer that things can only get better.

But this time I was 100 percent wrong.

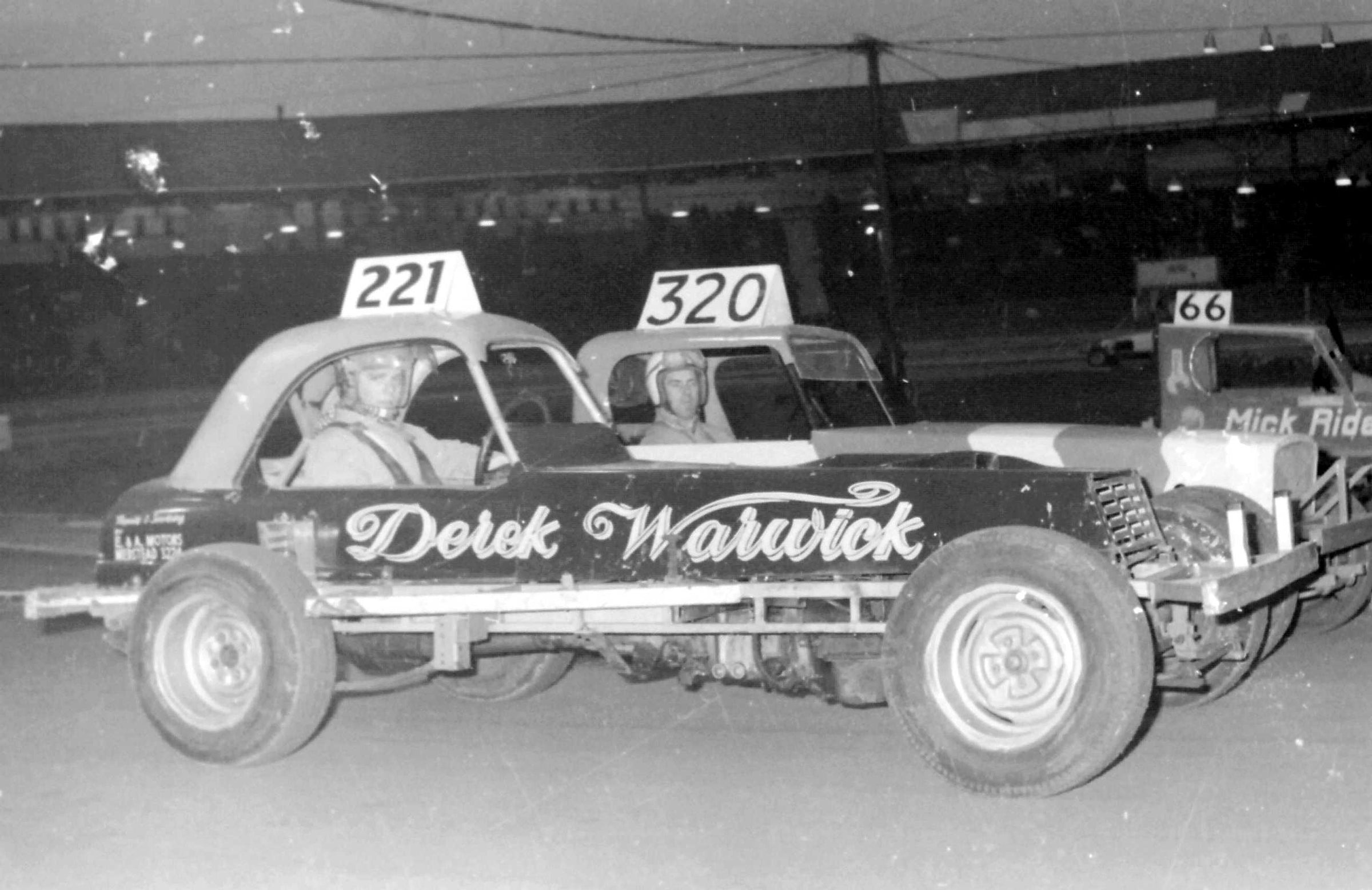

• Derek’s unconventional racing baptism saw him excel on short-track ovals, winning the World Championship at Wimbledon Stadium in 1973 aged 19.

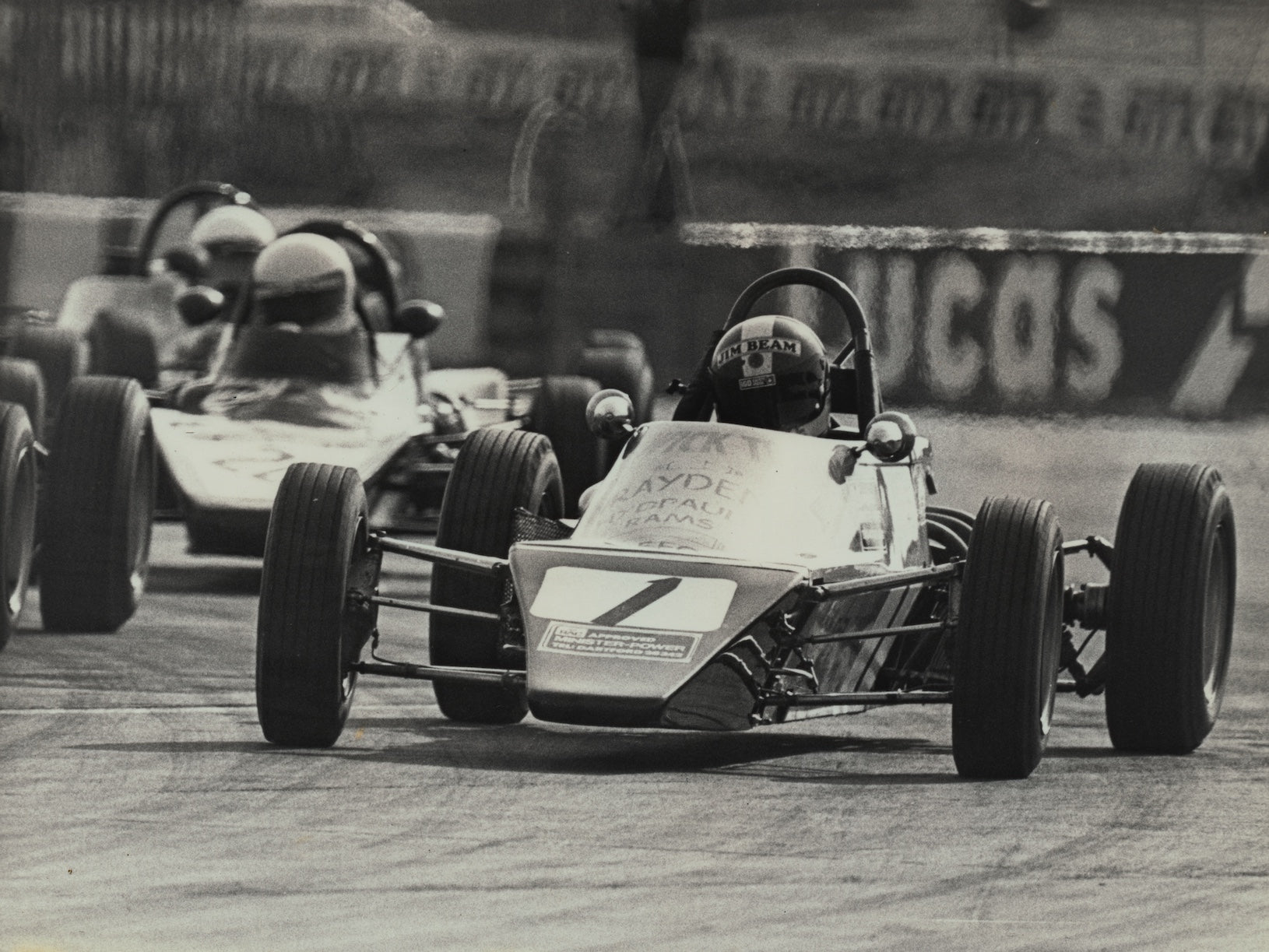

• Climbing the ladder: winner of 33 Formula Ford races and the European championship in 1976; champion in one of two major British F3 series in 1978 battling against Nelson Piquet and runner-up in the other; second in the European F2 Championship to Toleman team-mate Brian Henton in 1980.

• Into F1 with Toleman, gradually establishing himself as the fledgling turbo team gained momentum after a disastrous start in 1981–82, then scoring points in 1983 and becoming sought-after by other teams.

• After landing a plum seat at Renault for 1984, bad luck stopped him taking a deserved victory in the opening race, but he did achieve four podiums; but it all turned sour in 1985 with the team’s decline and then withdrawal.

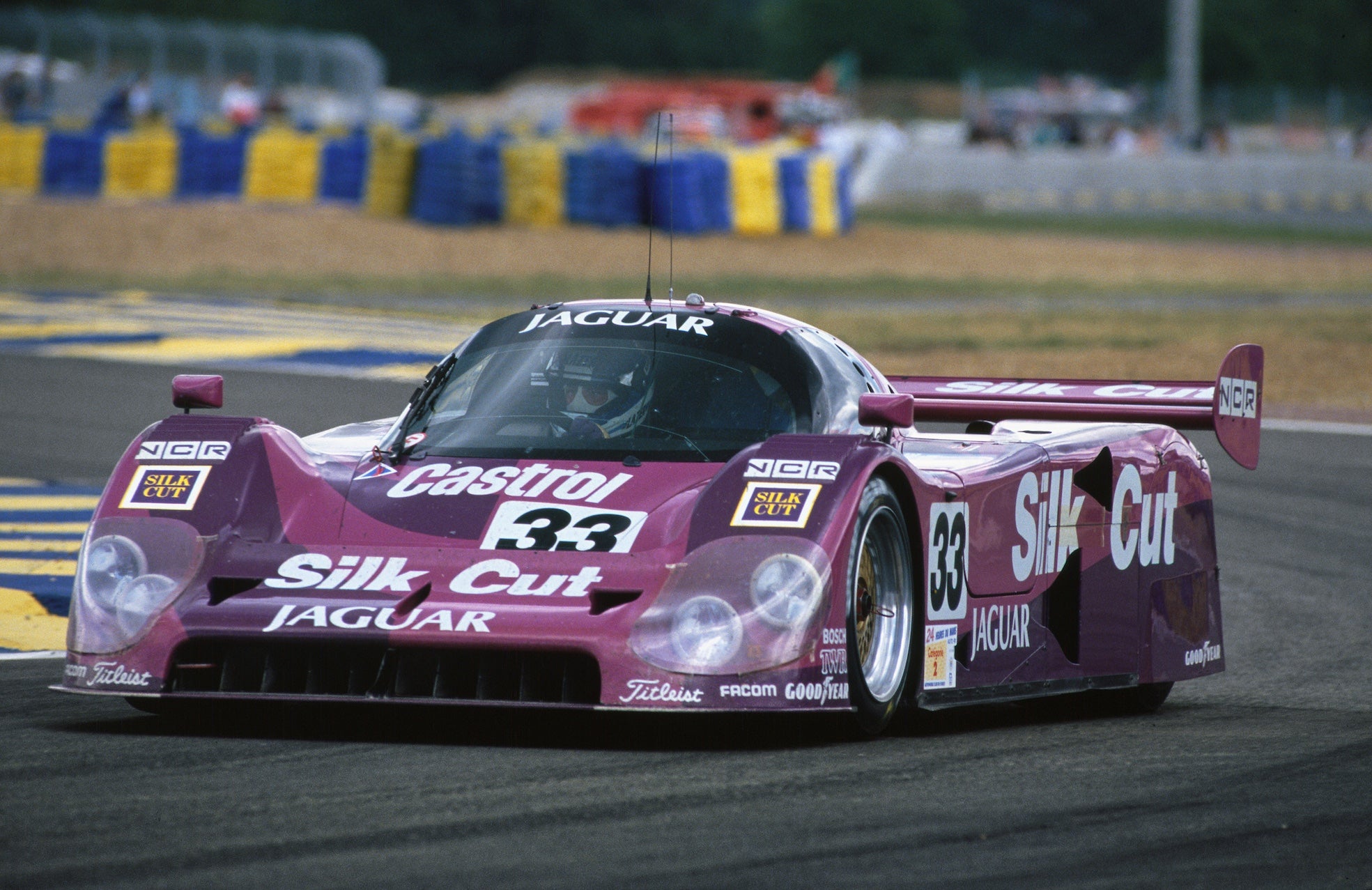

• With F1 opportunities drying up, Derek switched to the World Endurance Championship with Jaguar for 1986, finishing second in the standings; by mid-season, he also found himself back in F1 with Brabham after the sad death of Elio de Angelis.

• Three F1 years with Arrows (1987–89) saw him add to his reputation as a fast and committed racer, followed by a difficult season with Lotus (1990) that brought a huge accident at Monza and an even worse one for team-mate Martin Donnelly at Jerez.

• Back with Jaguar in a Ross Brawn-designed sports car for 1991, Derek won four races, but one disqualification meant he was runner-up in the Sportscar World Championship for the second time.

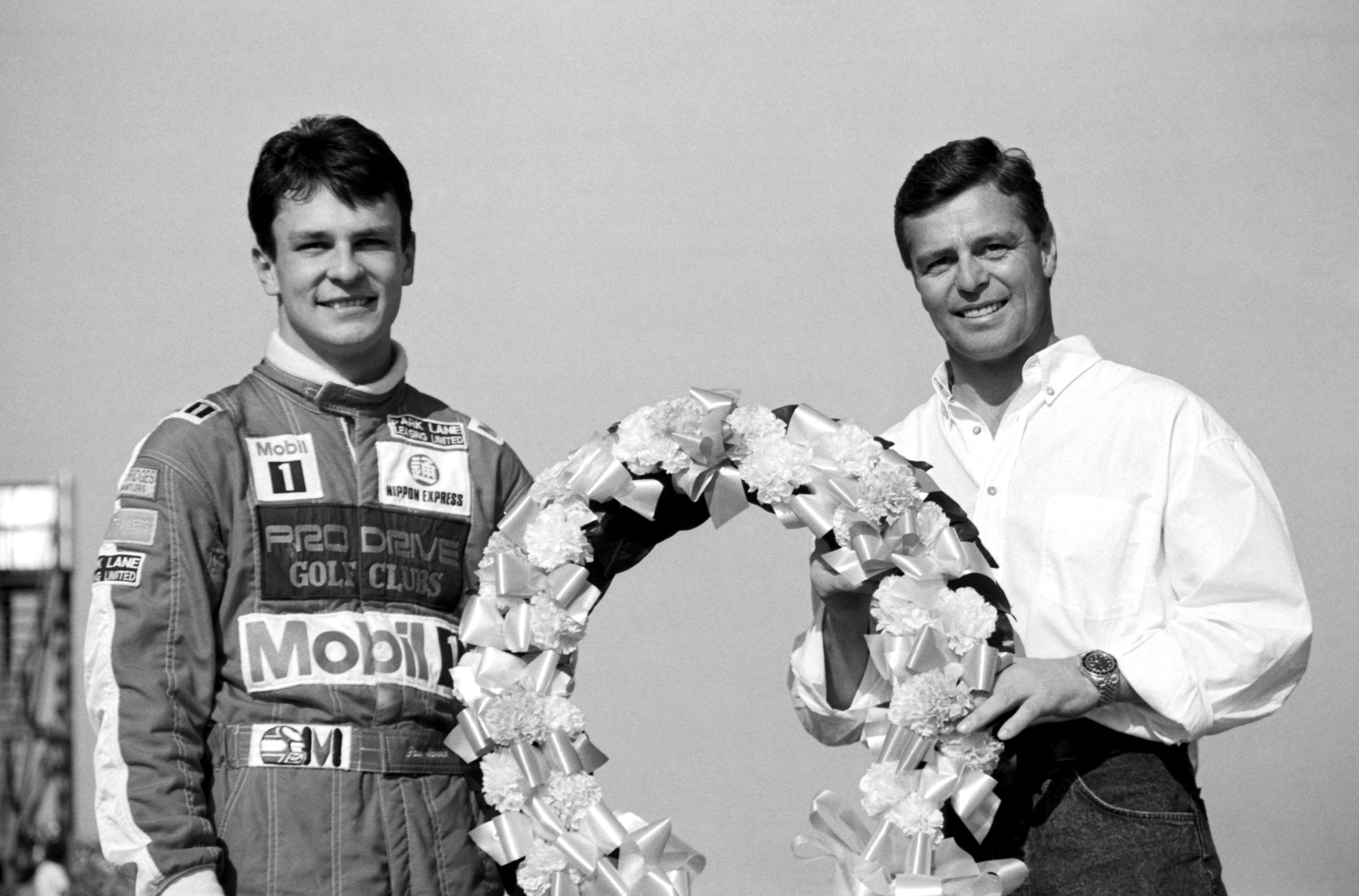

• On 21 July 1991, the Warwick family was torn apart when Derek’s younger brother Paul was killed at Oulton Park. Paul was pursuing a racing career of his own and had graduated to the British F3000 Championship, which he dominated and ended up winning posthumously.

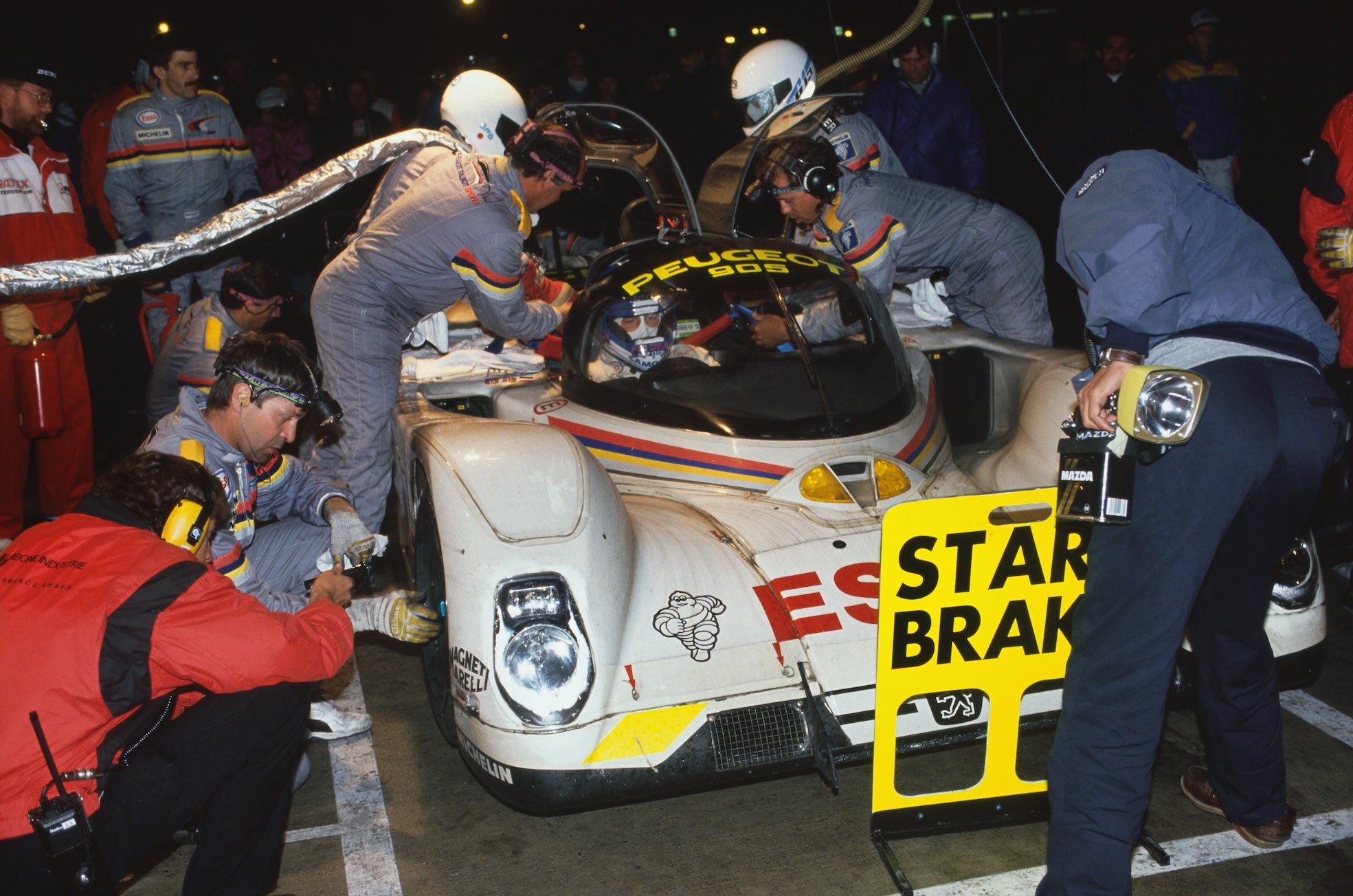

• World Champion again: invited to join Peugeot’s sports car team for 1992, Derek started to rebuild his life with a hugely successful year, winning both Le Mans and the Sportscar World Championship.

• One final year of F1 (1993), back with Footwork-branded Arrows, followed by some touring car racing, including with his own team 888.

• And more besides: he built up a small group of car dealerships in the UK and Jersey, selling the UK ones in 2003; he constructed or renovated over a dozen houses in Jersey, two of them at the time the most spectacular ever built on the island; ownership of three building companies in the UK; President of the British Racing Drivers’ Club; serving as an FIA steward at Grands Prix; coping with cancer.

Publication: 26 June 2024

Format: 270x210mm

Hardback

Page extent: 432

Illustration: 300, mainly colour

We deliver to addresses throughout the world.

UK Mainland delivery costs (under 2kg) by Royal Mail £5.00.

Books will normally be shipped within two working days of order. Estimated delivery times post shipment. UK: Up to 5 working days. Europe, Northern Ireland and Highlands and Islands: Up to 8 days. USA: Up to 12 days

IMPORTANT NOTICE FOR EU CUSTOMERS: Delivered Duty Unpaid (DDU) means that customers are responsible for paying the destination country's customs charges, duties. Regrettably parcels will sometimes be held by customs until any outstanding payments are made. Any payments not received may result in courier returning or in some cases destroying your books.

Unwanted products can be returned with the original packaging within 14 days of delivery. Returns will be at your own cost.

If you receive a faulty or damaged item please contact orders@evropublishing.com for return and replacement information.