Power Unleashed

Trailblazers Who Energised Engines with Supercharging and Turbocharging

- In stock, ready to ship

- Inventory on the way

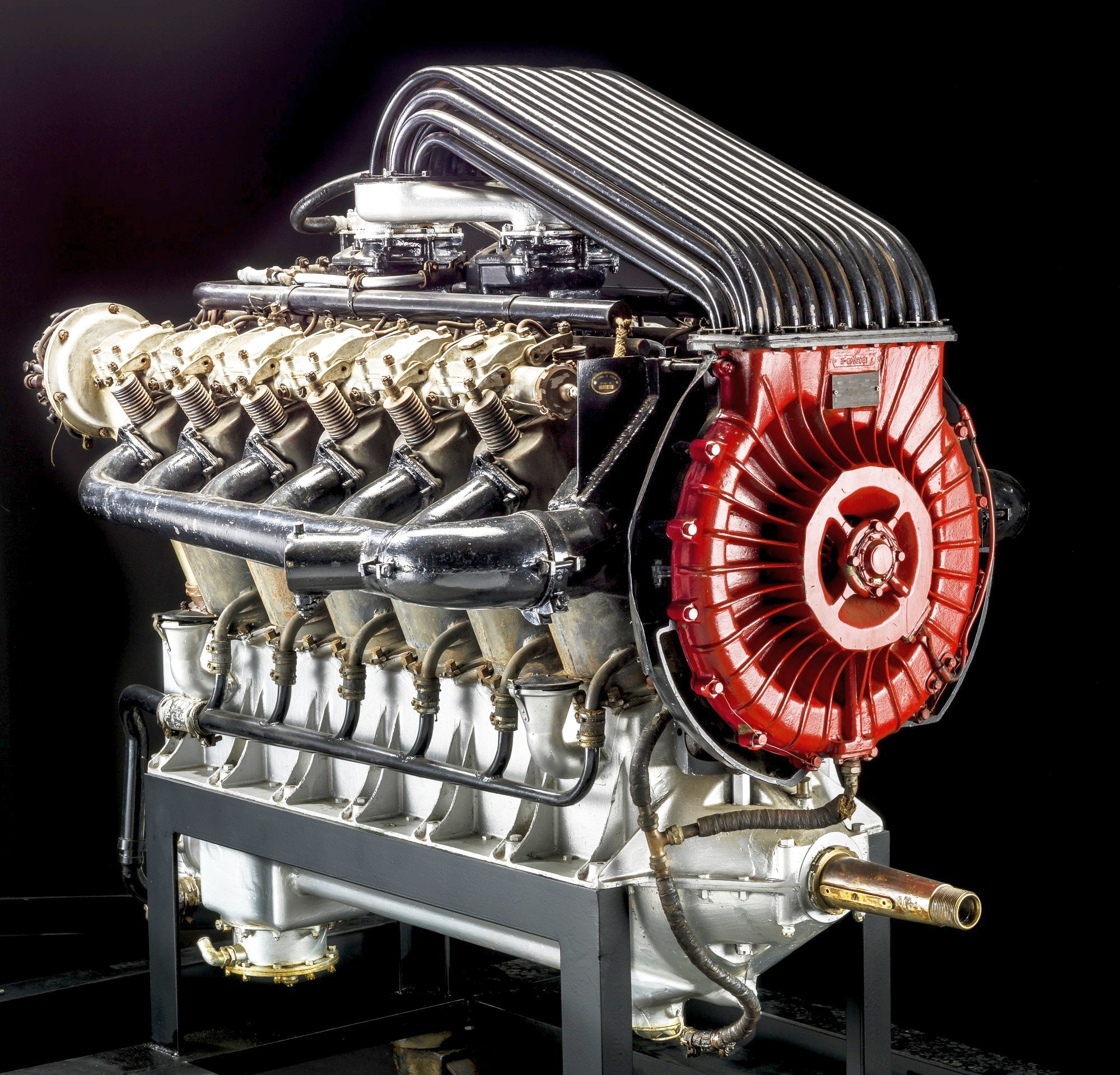

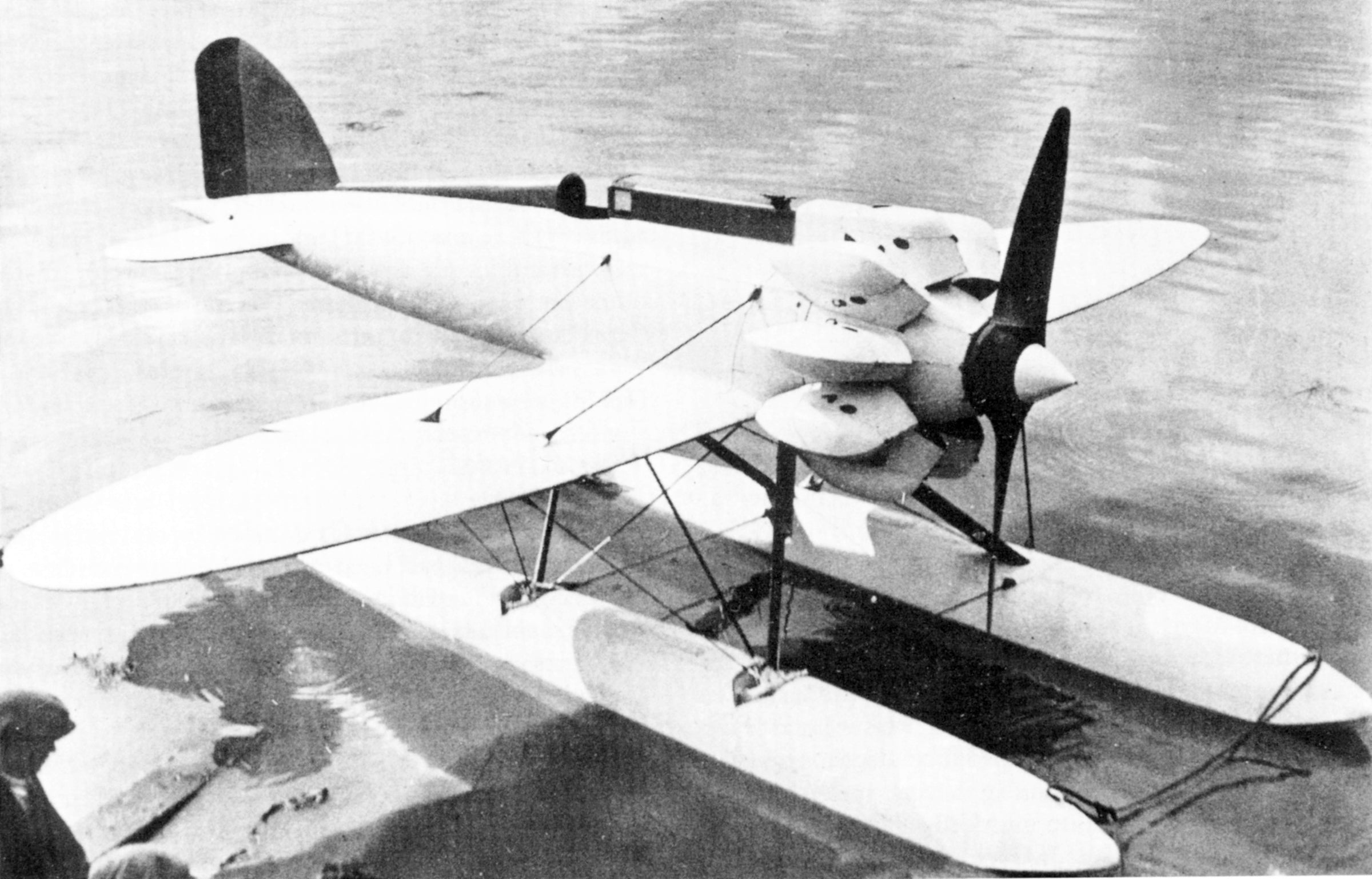

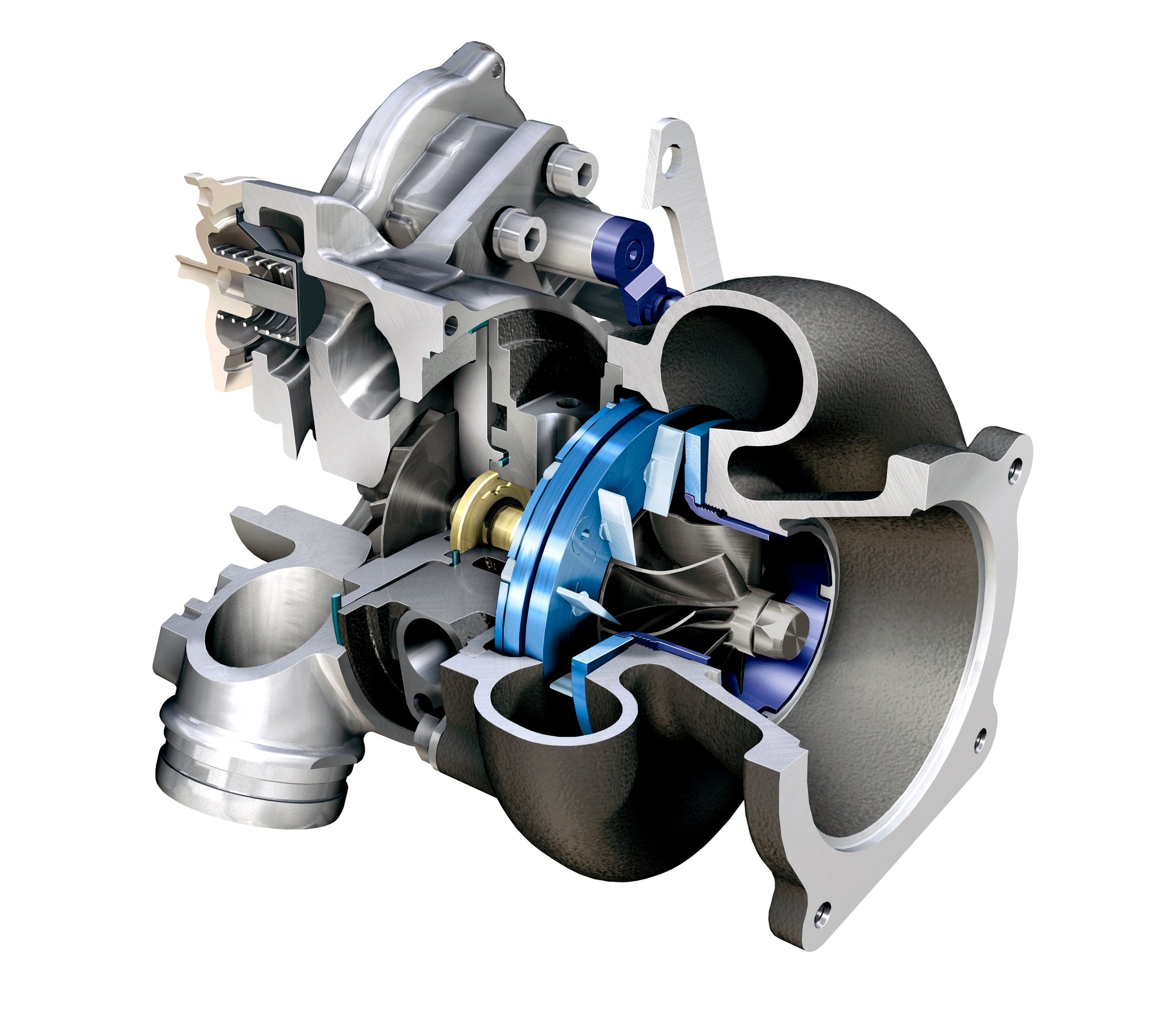

Prolific use of forced induction in the air in World War II brought forth the many engineering geniuses who populate these pages. Having seemed abandoned on land, supercharging found new acolytes who perfected blowers for road and track. They rescued the turbocharger to open new avenues for high-pressure boosting in the 1970s and ’80s. Into the 21st century turbocharging has found its way into more and more cars to enhance both performance and fuel efficiency.

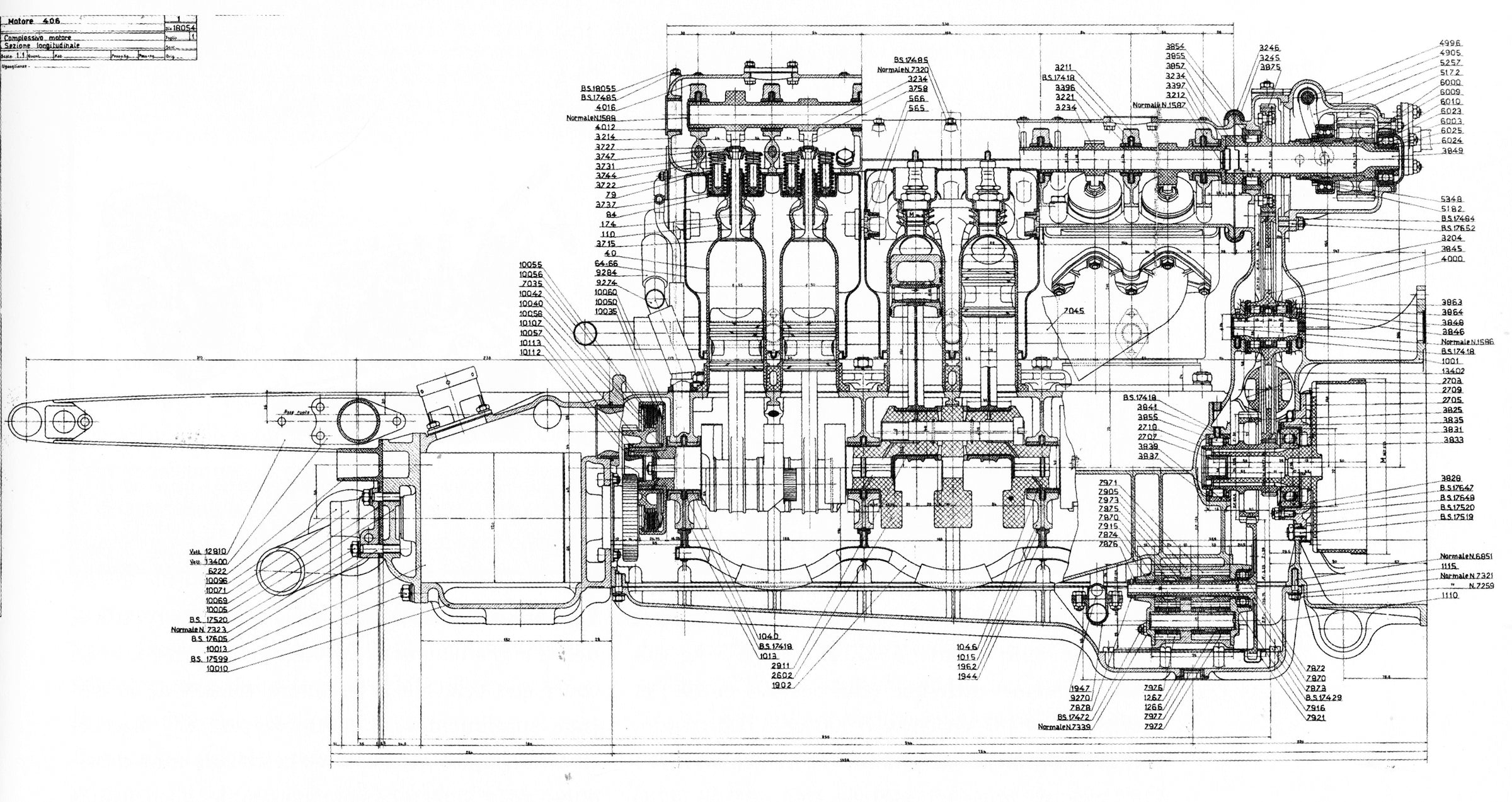

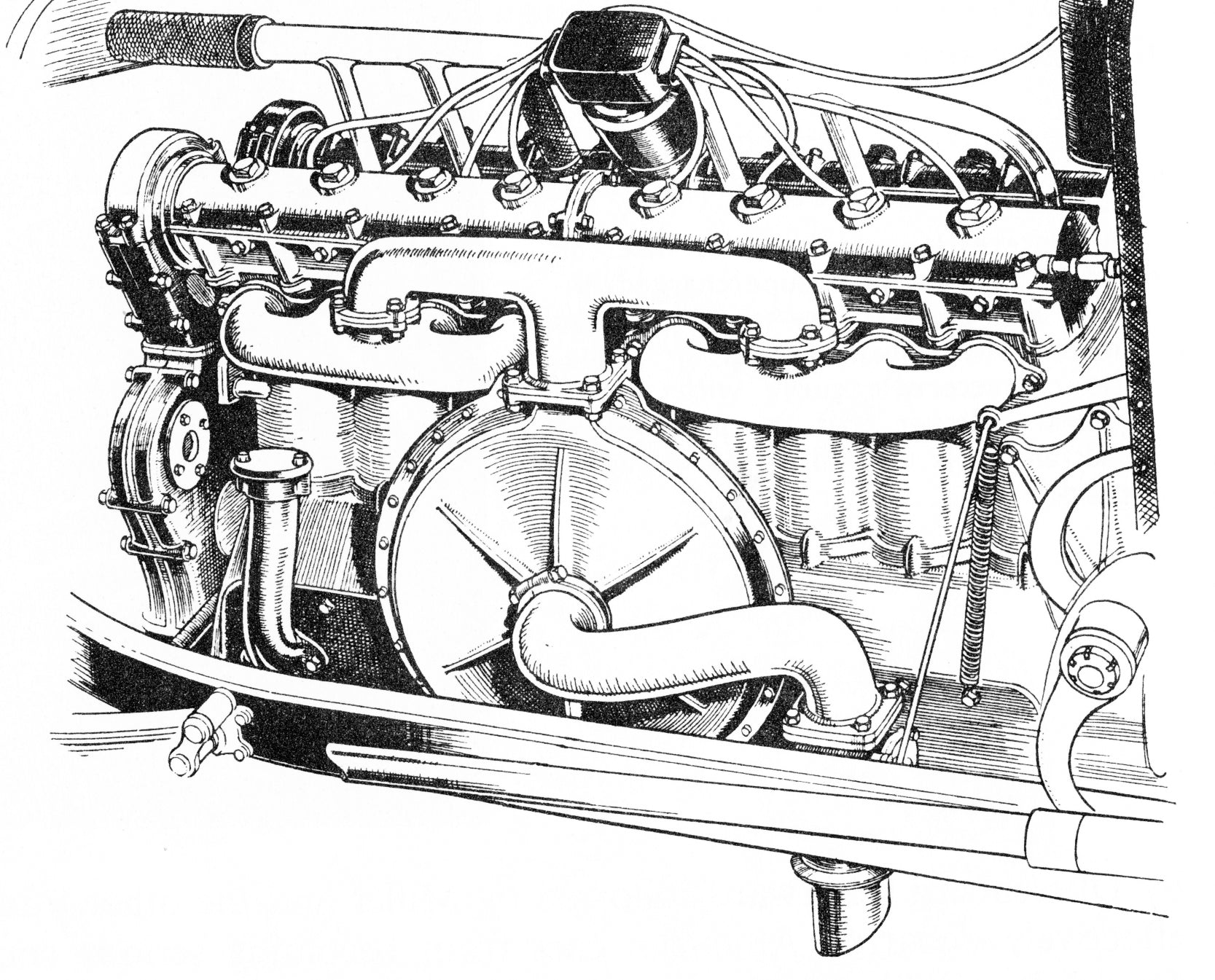

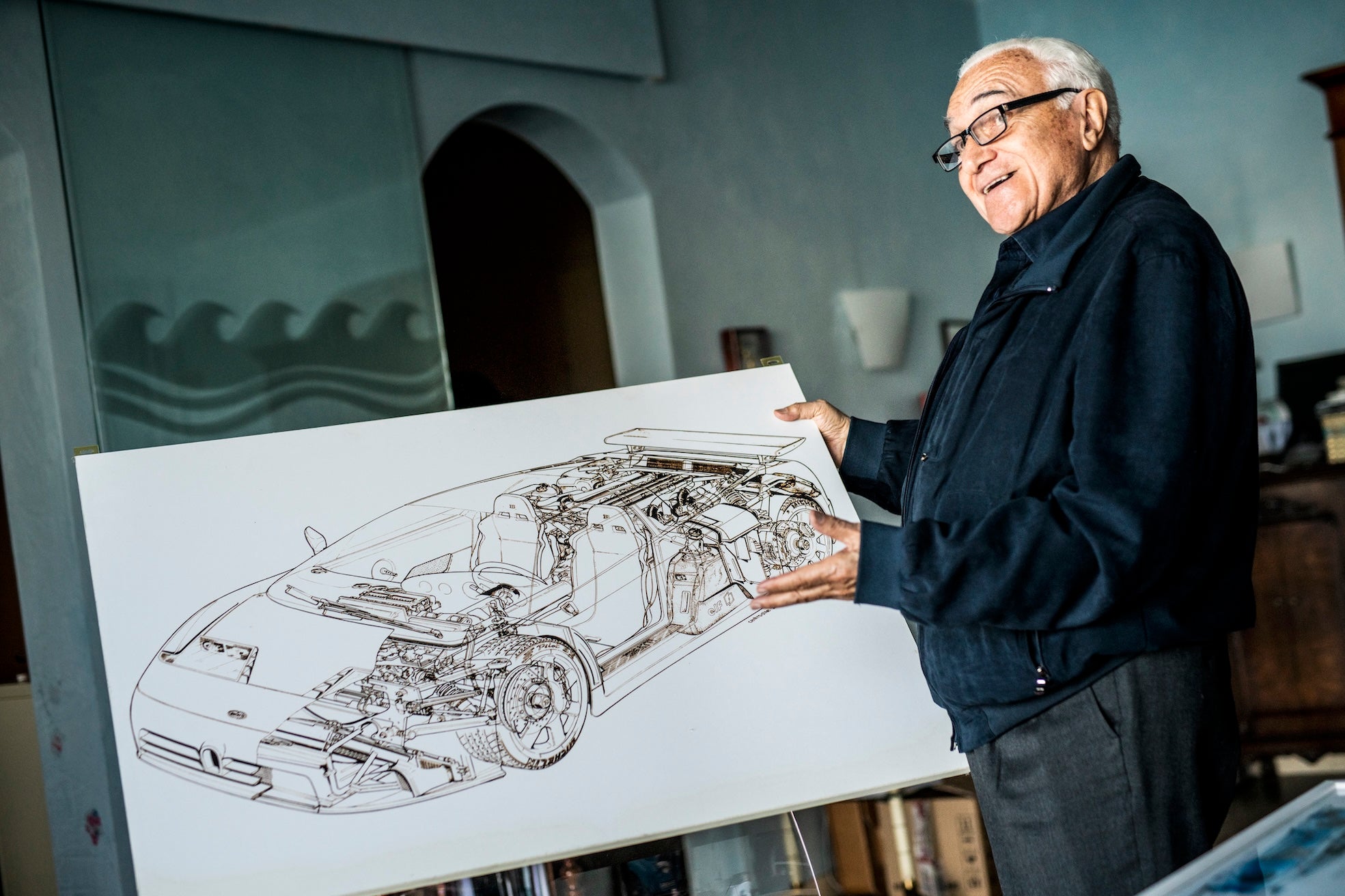

Power Unleashed is a three-volume work of astonishing depth and detail. Greatly respected for his ability to communicate information while telling a compelling story, Karl Ludvigsen explores the global saga of supercharging and turbocharging. Complete with reader-friendly technical descriptions and magnificent illustrations, he introduces the fascinating individuals who bet their businesses on boosting. This is a landmark work in the histories of the automobile and aeroplane.

PREFACE

Google Books has what it calls an Ngram Viewer. It charts the frequency with which words are mentioned in texts. Supercharging and superchargers start picking up from 1920 and by 1940 have reached dizzying heights. They slope down again and by 1970-80 are moribund. Thereafter they show life as does turbocharging, which first held its hands up around 1945.

I realise that does not fully reflect the identity of the forced-induction technology that is the subject of these volumes. We have been bombarded for years to ‘Supercharge your Workout’, ‘Supercharge your Social Media’, ‘Turbocharge Smart Nation Projects’, ‘Turbocharge Your Trading Profits’, ‘Supercharge Your Studying’, ‘Supercharge Your Metabolism’, ‘Turbocharge Your Golf Game’ and (real example) ‘Turbocharge Any Dog Food.’

Then there’s Elon Musk with his ‘Superchargers’. Etched in history is the second Battle of El Alamein in North Africa between 23 October and 2 November 1942. Considered ‘the final decisive military achievement of Britain as a great power,’ it went down in history as ‘Operation Supercharge’. The term has earned its place in the lexicon.

While working on this history I have taken comfort from the way forced induction has advanced in its use on the world’s automobiles. Turbulent though diesels have found recent markets, they are turbo users with few exceptions. In 2019 the general use of turbos in new cars, accelerated by downsizing, passed the one-third mark. Making and marketing turbochargers and electrochargers is now big business, if progressively less for conventional engines then more for air supplies to fuel cells and hydrogen powerplants.

Positive-displacement superchargers are still charging along, thanks in part to remarkable advances in design and application. One Chevrolet, one Ford, one Jeep, one Lotus, two Dodges, four Jaguars, four Land Rovers and five Volvos are supercharged as of this writing. Their use is favoured for vehicles that offer the ultimate in power and thrust.

Many patents down the decades are shown and referenced in these volumes. Throughout I have identified them by their dates of submission to the authorities. I take this to refer best to the time when the invention was conceived.

As for my own involvement, I can hark back to 30 January 1955 when, with my colleagues Donald G. Typond and David K. Hanser, I submitted a proposal in my studies of industrial design at Brooklyn’s Pratt Institute titled Engineering Considerations in Proposed Sports Car Project. Although we actually had in mind designing and building such a car, this did not eventuate. When discussing its engine I wrote the following:

Some of these thoughts found their way into an article published in the July 1958 issue of Sports Cars Illustrated, where I had just vacated the chair of technical editor to begin a two-year stint with the U.S. Army Signal Corps. Titled The Blower Route, it presumed to follow a three-part series on supercharging in the same publication starting in August 1956 written by established expert Roger Huntington.

While in Germany with the Signal Corps in 1958-59 I wrote my first complete book, Your Sports Car Engine, for New York’s Sports Car Press. I dedicated Chapter 4 to the topic of supercharging. A sign of the times was that I didn’t mention turbocharging, even though a turbo-blown Cummins Special had demolished the qualifying records at Indianapolis as recently as 1952. I wasn’t the only one who didn’t take notice. I made up for it by commissioning an article from William Carroll on turbocharging that appeared in the September 1957 Sports Cars Illustrated. ‘The blower of tomorrow is available today,’ he signed off insightfully.

At the end of 1961 I joined General Motors in public relations with a remit chiefly on Styling Staff but allowing me some scope on outward-facing activities at the Technical Centre. When GM divisions Chevrolet and Oldsmobile introduced turbocharged production cars in the spring of 1962 I saw this as a major coup for GM that deserved technical coverage. Britain’s Automobile Engineer agreed with me so I researched the origins of both systems in depth, aided by Engineering Staff’s Darl Caris, who had overseen GM’s earliest studies. My story was published in the February 1963 issue—uncredited as customary.

When I left GM in 1967 to pursue a freelance career one of my better customers was Automobile Quarterly. I don’t recall exactly how it came about, but we agreed that I would write a piece that we titled The Origins of Supercharging. Published in the Fall-Winter 1970 issue, Volume IX Number 2, it carried the story up to the mid-1920s when many of the relevant principles had been established.

In writing this I had the great advantage that some of the principals of those early days were still available to help me. Outstanding among these was Cornelius Van Ranst, who not only designed and built but also raced a two-stage-blown front-drive Miller at Indianapolis in 1927. I also spoke with David Gregg, who designed the first centrifugal superchargers used by Duesenberg at Indianapolis in 1924. An improved version took Pete De Paolo to victory in the 1925 500-mile race. David pops up in several chapters.

I sent David Gregg a copy of the relevant issue of Automobile Quarterly. ‘To the best of my knowledge,’ he replied, ‘your article is the first and only comprehensive account of supercharger development. You have done a tremendous job of research and investigation in accumulating the necessary facts. My sincere congratulations to a thoroughly competent professional, who has done an outstanding service to the engineering field by presenting your comprehensive and in-depth article.’

I received indirect praise of my article eight years later from an old friend, Griffith Borgeson. In a brief letter mentioning Sanford Moss he referred to yours truly ‘…as the best writer there is on the subject of supercharging…’

Forty years after publication of the AQ article I decided to finish the job. I found a lot more to say about the first 25 years and, of course, far more than I expected in the subsequent nearly-100. Word count skyrocketed after I dug more deeply into the Great War’s important boosting advances. That meant my having to do similar justice to World War 2!

Work on the book began in 2010 when my original contract with Haynes was executed. After Haynes stepped down the project was accepted by Evro, who have been ever so patient when a couple of other projects interrupted me. Over this period I have been constantly uplifted by encouraging remarks from my interlocutors.

An example is Dan Whitney who, after reading my outline for the book said, ‘I think you have a winner here. A very ambitious project but one that should be interesting to a wide range of readers, as well as important to the history of the motorcar and supercharger.’

Also heartening is a note from Robert D. Hansen, whose company’s unique amendment to the Lysholm supercharger is described in chapter 44. His letter included the following:

‘Commendations for your distinguished and fruitful career in support of the automotive industry and its millions of driver beneficiaries and their occupants. Thank you also for giving voice to the thousands of engineers and other employees who designed generations of power trains which have supported the transportation demands and aspirations of our economy and culture.’

I’m happy with the result and hope you will be too.

VOLUME 1 INTRODUCTION

We discover supercharging in action as soon as there are high-speed engines small enough to be mobile. After Nikolaus Otto’s four-stroke principle is validated, its performance is seen to depend on its ability to inhale the atmosphere’s combustion-giving oxygen. Once oxygen is there, it’s just a matter of mixing it with fuel and lighting a match. Or, in the case of Rudolf Diesel’s invention, compressing it enough to self-ignite.

Here is an engraved invitation to take steps to introduce more air than atmospheric pressure provides. This turns out to be more difficult than many expect. There is the need to use less energy to introduce the bonus oxygen than its introduction generates. Added weight and complexity need to be dealt with. Engines themselves have to cope with more internal stress than is at first envisaged.

Volume 1 brings a number of influences to the forced-induction party. One is the two-stroke engine as championed by Dugald Clerk. Clerk’s definitive two-stroke engine is first displayed in 1881. To complete its cycle it needs a source of compression to speed the exhaust on its way and introduce a fresh mixture. A blower can achieve this and, if cleverly deployed, raise induction pressure above atmospheric.

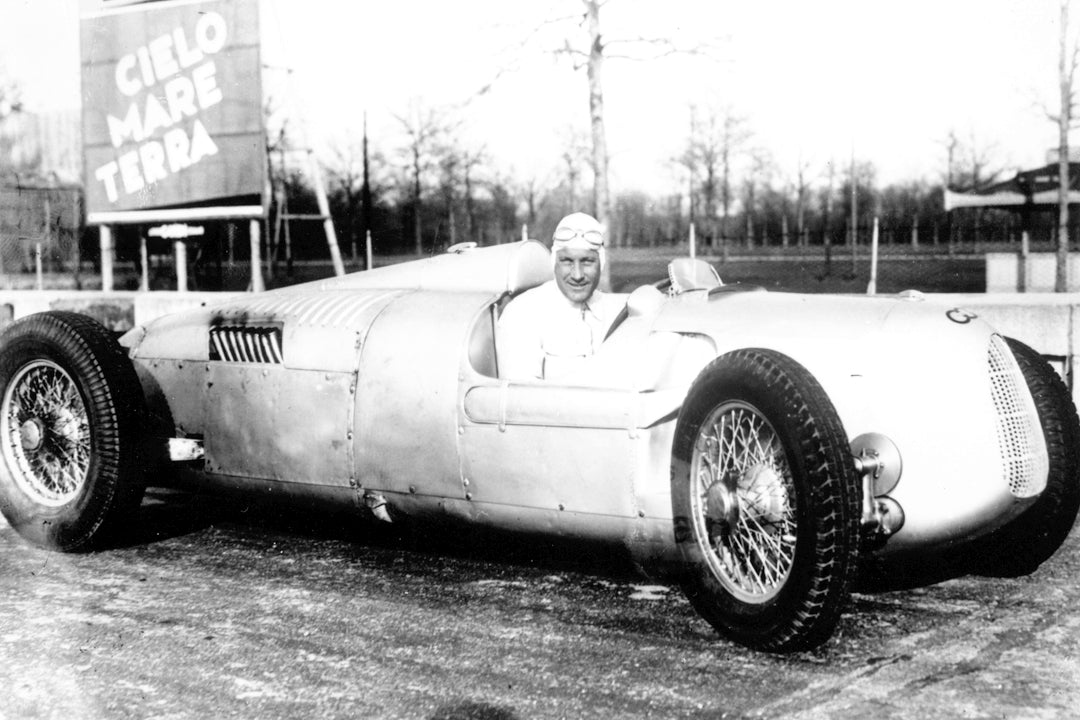

Another is influence is motor racing. The use of forced induction initially focuses on categories that are in limited, by cylinder bore or displacement, because boosting provides a way to produce more power in spite of these limitations. This volume extends into decades when supercharging of racing cars becomes bitterly controversial.

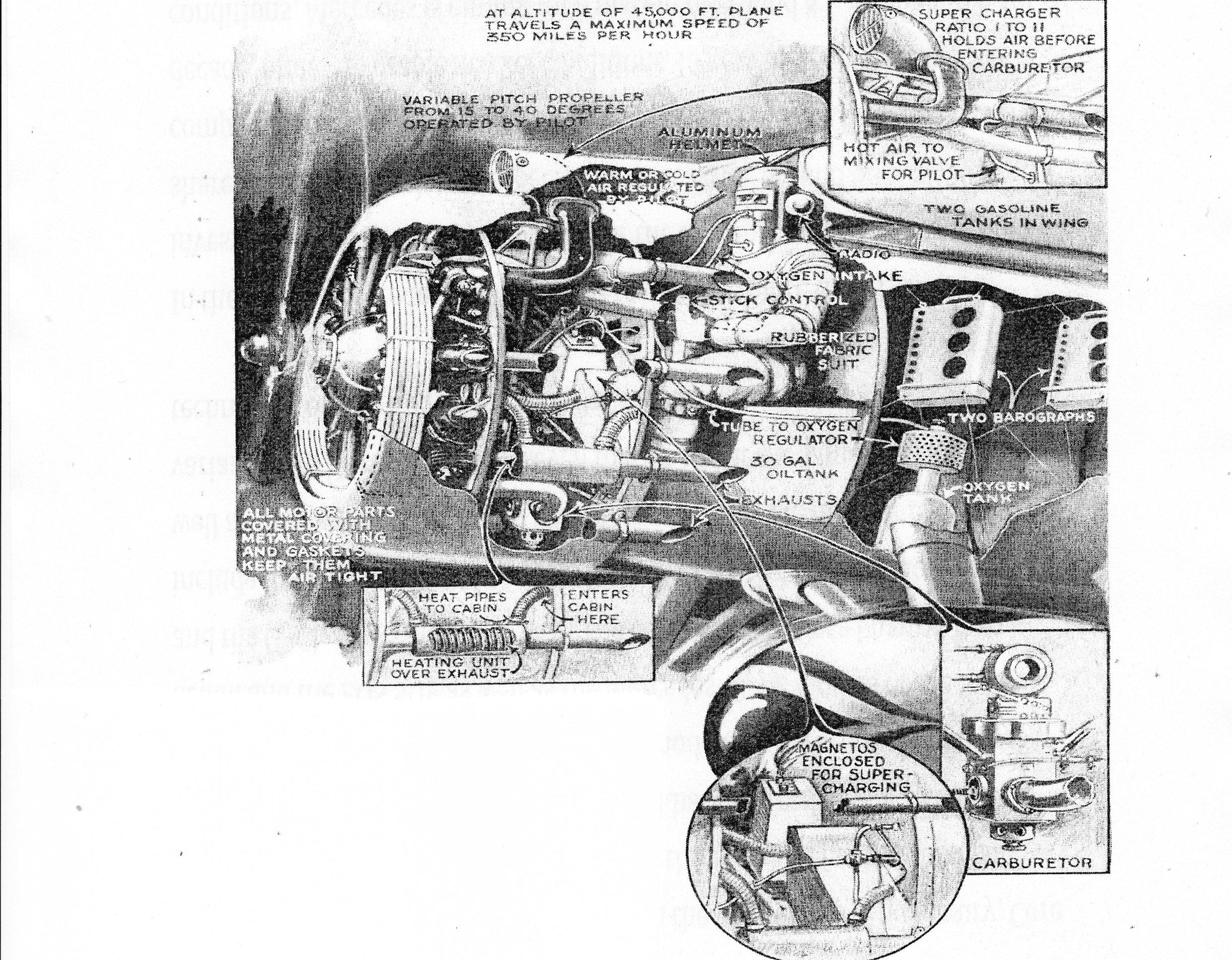

This volume also embraces the Great War of 1914-1918. This experiences astonishingly rapid development of aviation and the engines that power it. Soon this shows the advantages of altitude in causing and avoiding damage and with it the value of supercharging. Although not implemented early enough to have significant effect, aero-engine boosting delivers technologies to peacetime that are soon taken up.

One such technology makes only sporadic appearances. This is turbocharging, or turbo-supercharging as it is originally known. It makes progress for aviation late in the war but afterward lays fallow until the prospects of another conflict loom. Available to researchers are the principles of its turbine and compressor elements as set out by Aurel Stodola, whose Zürich laboratory supports the work of pioneers. Only a handful attempt to use turbos in motorcars.

Among those pioneers are Marc Birkigt, Louis Renault, Arnold Zoller, Alfred Büchi, Auguste Rateau, Sanford Moss, James Ellor, David Gregg, René Cozette and Chris Shorrock, to name some of the most significant. In these pages we see their creation and application of all the prevailing compressor types. They include the Roots, centrifugal, vaned and Lysholm screw-type blowers that populate these writings in their immense and fascinating variety.

VOLUME 2 INTRODUCTION

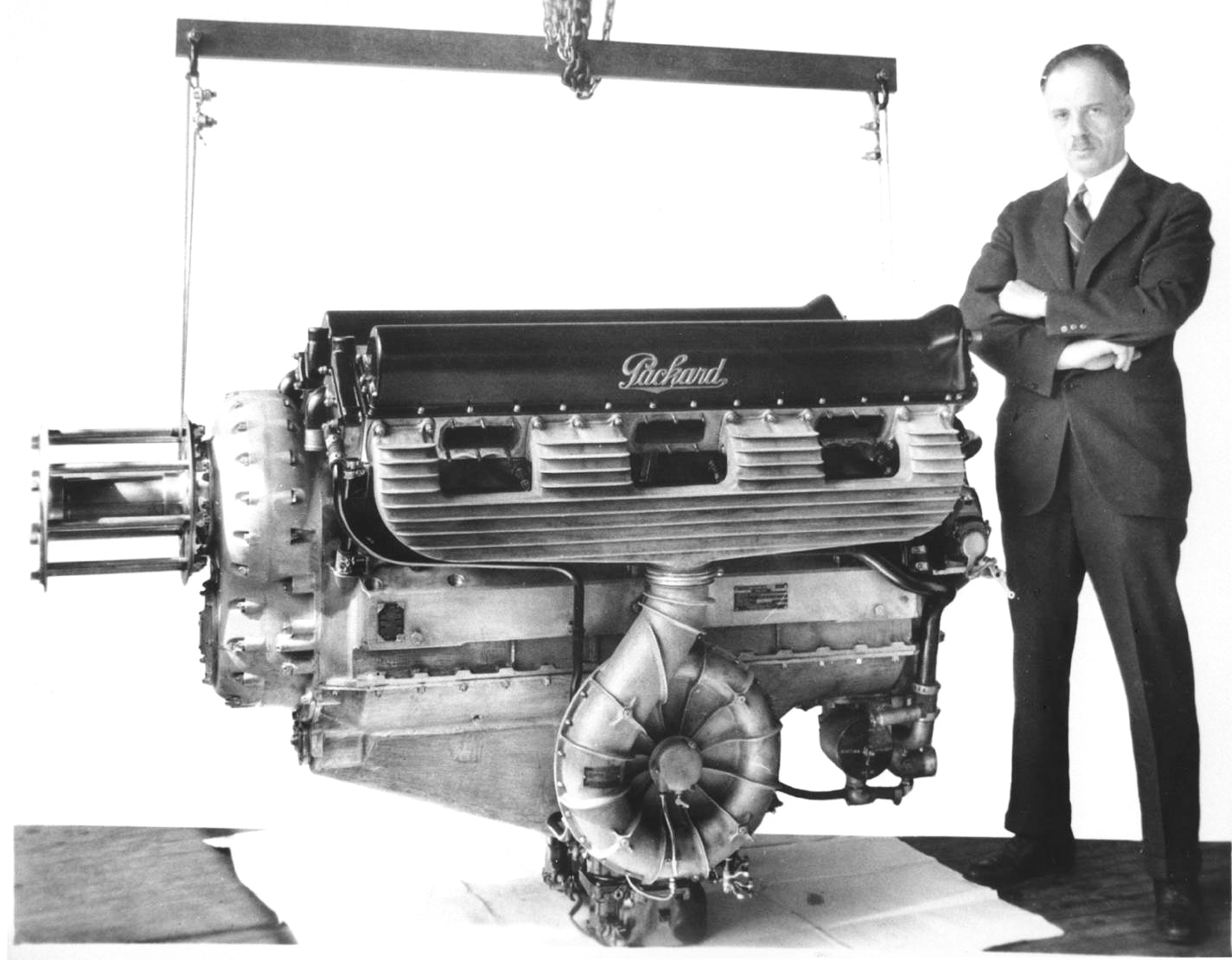

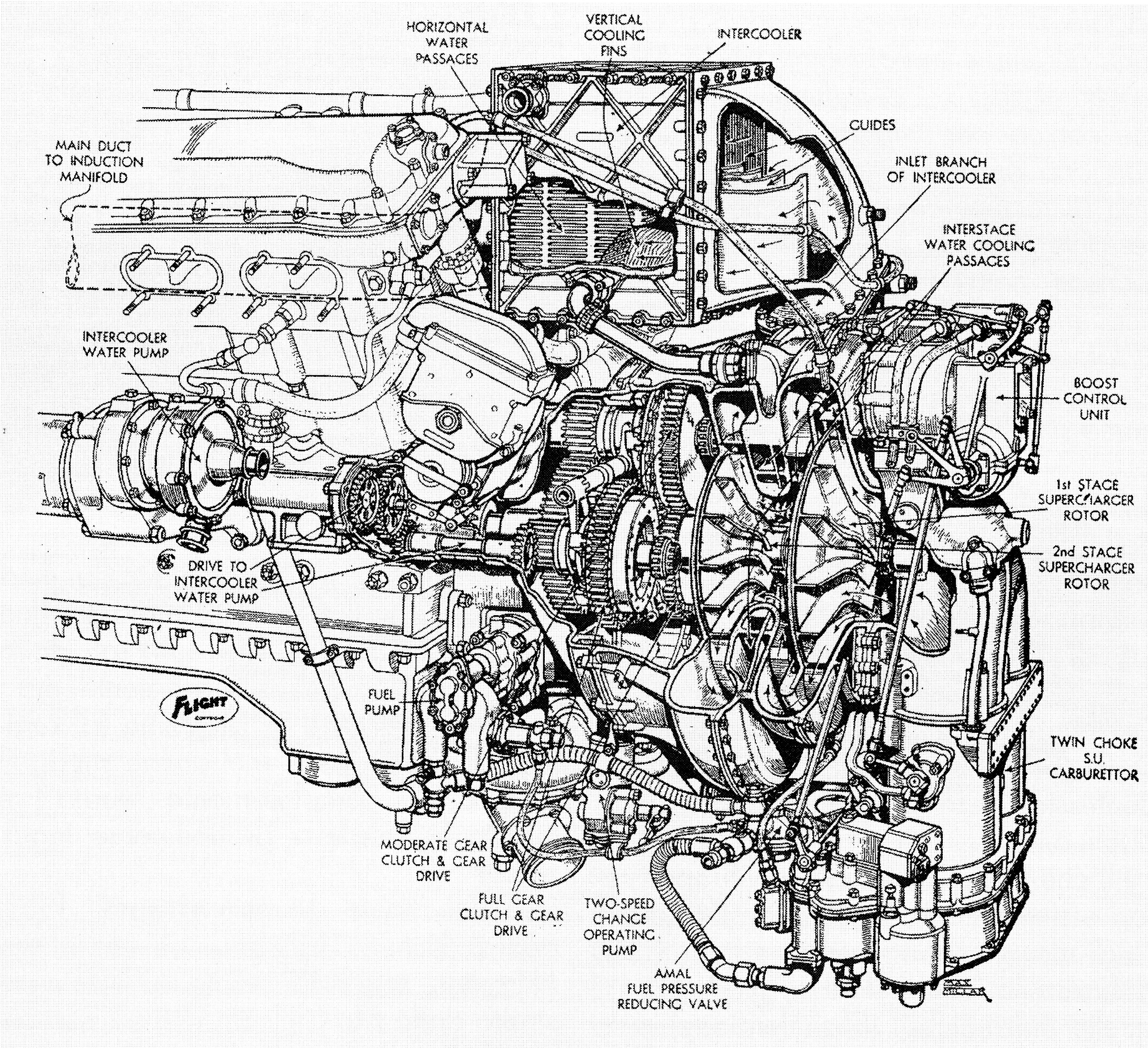

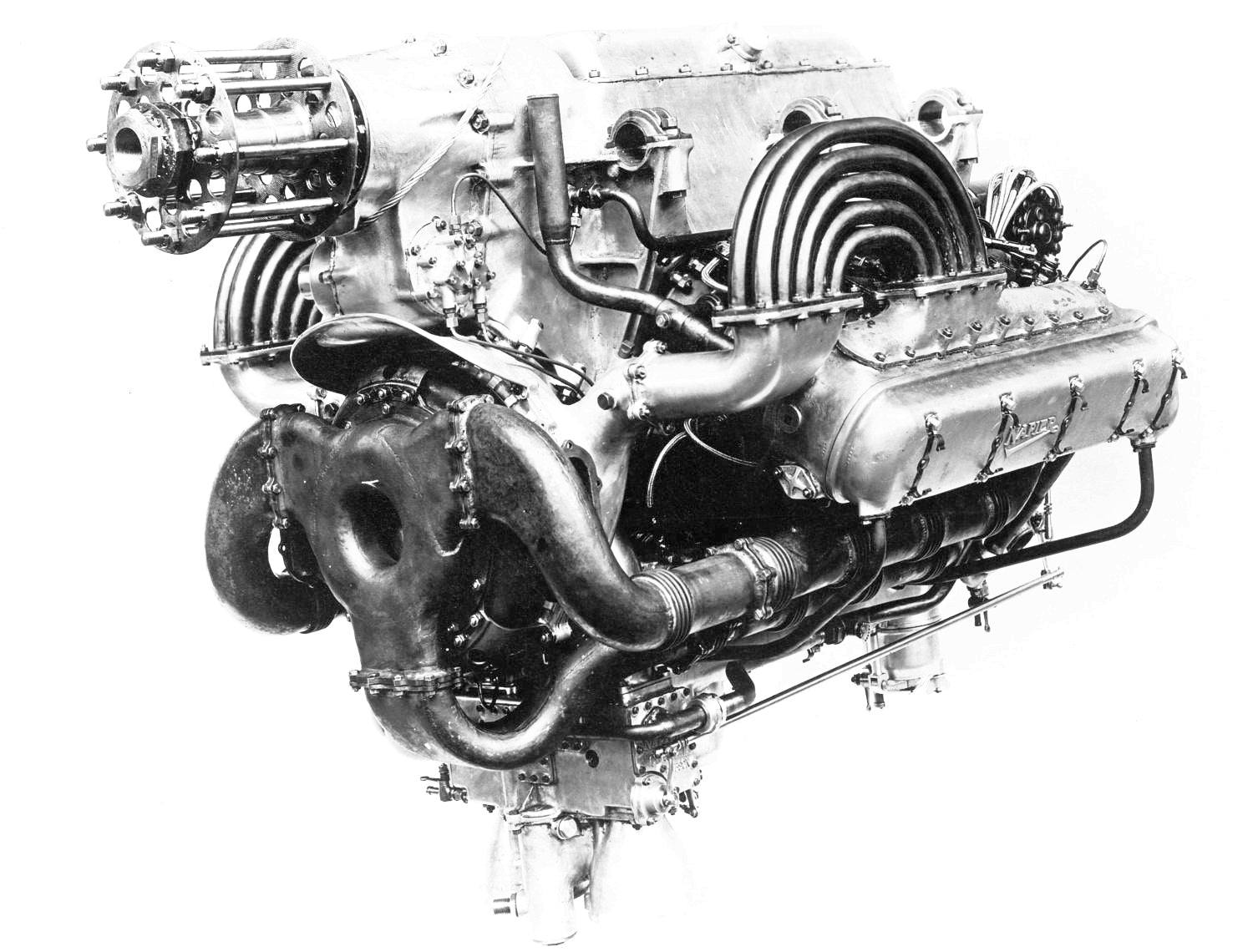

Looming over the events of Volume 2 is World War 2. Eight of this volume’s 15 chapters are dedicated in whole or in part to the evolution and application of airborne supercharging and turbocharging to serve in those crucial years from 1939 to 1945. Having covered supercharging in the Great War, the author sees no alternative to giving similar treatment to its benighted successor.

The war years are relevant for the impetus they gave to supercharging technology, including components that are used in gas-turbine prime movers and vice versa. Centrifugal blowers and turbochargers evolve hand in glove with the vital components of the first successful gas-turbine jet engines for aircraft.

Power-adding systems that flourish aloft such as nitrous-oxide injection, water/alcohol addition and oxygen injection are proven in battle, as is fuel injection—all later used in automobiles. So is the concept of two-stage charging. Introduced just before the war in motor racing, it is then exploited in airborne supercharging before its adoption in Formula One racing.

New names appear as the designs and applications of forced induction evolve. Among them are Michael McEvoy, Louis Schwitzer, Frank Arnott, Floyd Kishline, James Allison, Charles Waseige, Frank Halford, Cliff Garrett, Michael May and Ralph Broad. Special mention is made of Robert Paxton McCulloch, who makes his bow in Chapter 21 as a producer of Ford conversion kits and then Roots blowers in wartime service. The next chapter is devoted entirely to McCulloch, his variable-speed centrifugal blowers and their exploitation by the Granatelli brothers.

In the 1920s and ’30s such marques as Duesenberg, Stutz, Invicta, Alvis, Lea-Francis and Lagonda enjoy the benefits of Roots, vane or centrifugal boosting in their production cars. Graham-Paige launches a supercharged model in 1934 to designs from Floyd Kishline. Auburn and Cord join the party, sharing an ingenious centrifugal blower from Schwitzer-Cummins designed by Kurt Beier and Herman Winkler. In 1935-40 Milwaukee’s Ray Besasie builds and sells turbochargers for American autos. Turbocharging makes progress in diesel engines, whose lower exhaust temperature is kinder to the turbine blades.

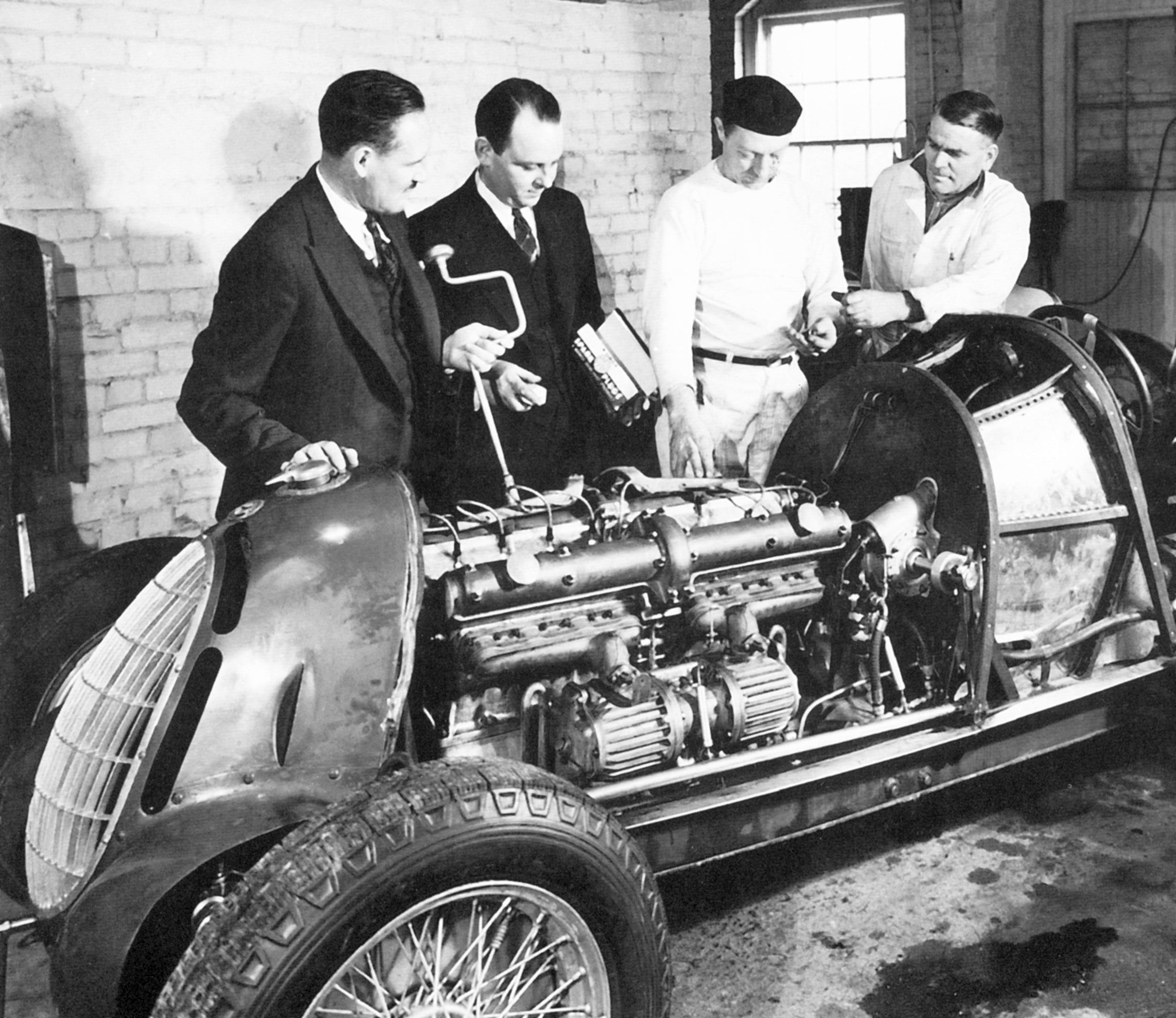

Formerly a wartime engineer in Germany, Ted von der Nüll brings to Garrett AiResearch the breakthrough peripheral-entry turbine he developed during the war for vehicles fuelled by generator gas. In the 1950s General Motors researches turbocharging. When two divisions decide to go turbo, von der Nüll’s tiny AiResearch turbocharger suits a 1962½ Oldsmobile while Chevrolet gets one from TRW. International Harvester turbo-boosts its Scout. The age of mainstream turbocharging has arrived—briefly.

Turbos get a boost at the end of the 1960s when Swiss engineer Michael May decides to design and make kits for a German Ford V-6 engine. His systems find acceptance and inspire BMW to take up the technology. Its 2002 Turbo launches in 1973. Soon turbocharging is adopted by Porsche, Buick and Saab-Scania, which stays true to the technology to the 21st century. The turbo is on its way.

VOLUME 3 INTRODUCTION

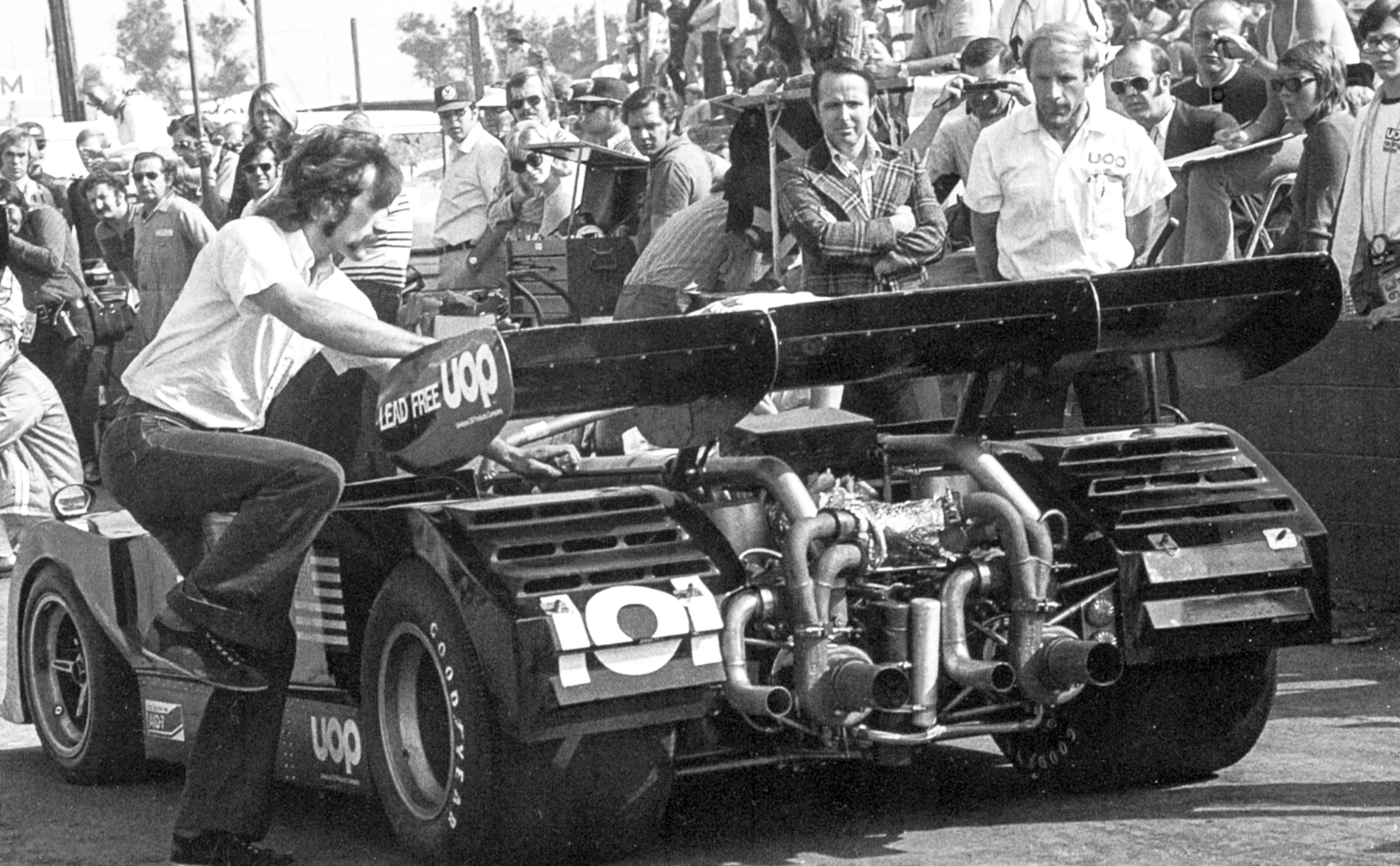

Volume 3 starts with a bang! Its first six chapters are strictly reserved for the turbocharging of racing cars. Dominating the scene are two great events: the annual Indianapolis 500-mile race and the Canadian-American Can-Am Challenge for Group 7 sports-racing cars.

It begins at Indianapolis, where the Cummins Engine Company enters a car in 1952 that is turbocharged—the first in Indy history. Its speed in qualifying is electrifying but its race pace is mediocre. In 1966 Indy Offy-engine maker Meyer-Drake builds 2.75-litre fours to race boosted against the Speedway’s 4.2-litre unblown limit. When a turbo is applied in 1967 the ground is laid for a turbo Offy to win in 1968. Henceforward turbocharged engines prevail at the Speedway.

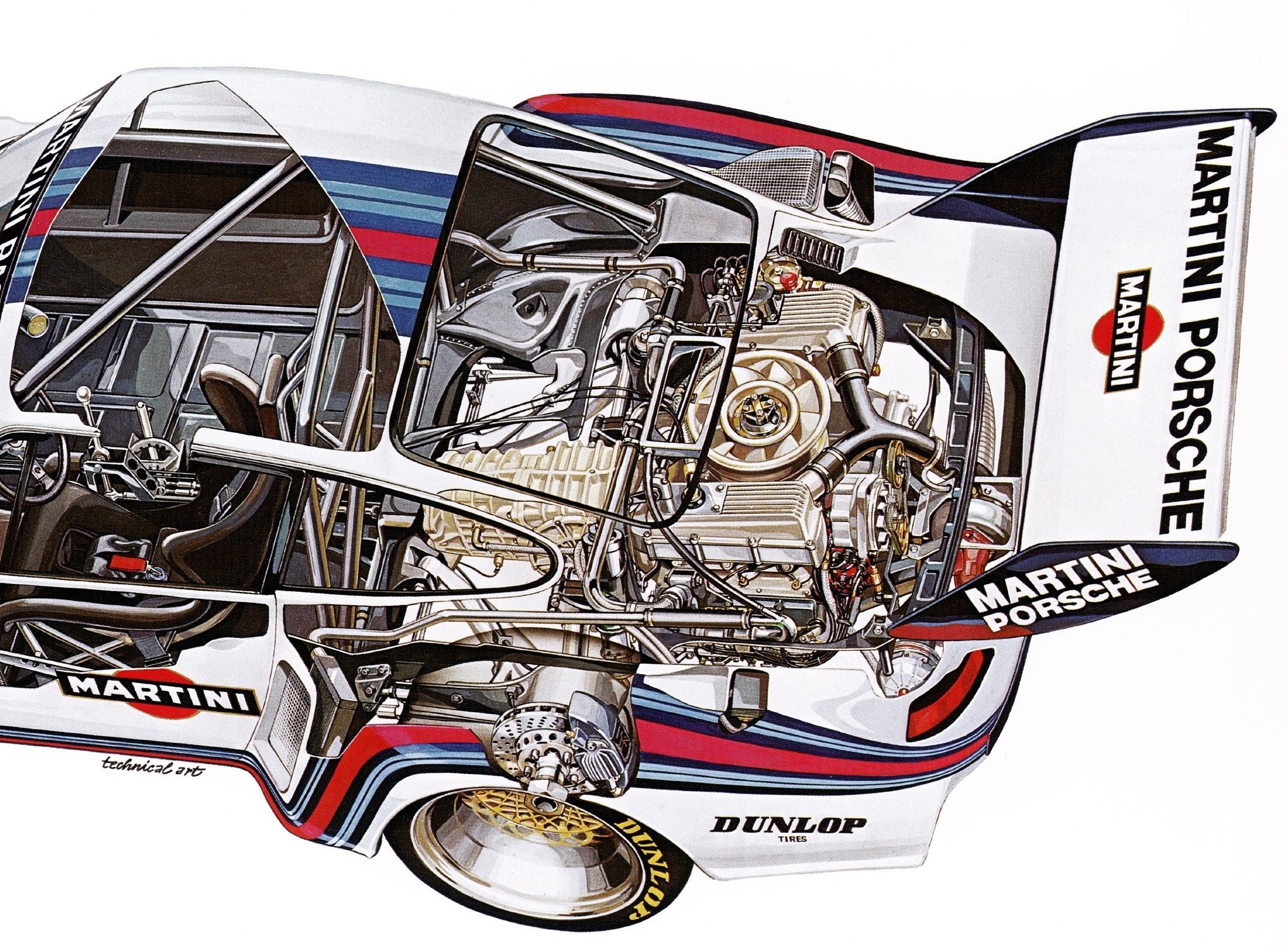

The Can-Am picture is different. Although two teams use turbos on big V-8 engines in 1969 and ’73, neither races them successfully. A Toyota effort in 1969-70 is abandoned. Only Porsche succeeds, its turbo-powered racers dominating the series in 1972 and ’73. Thereafter Porsche exploits turbocharging in racing through the 1980s and beyond.

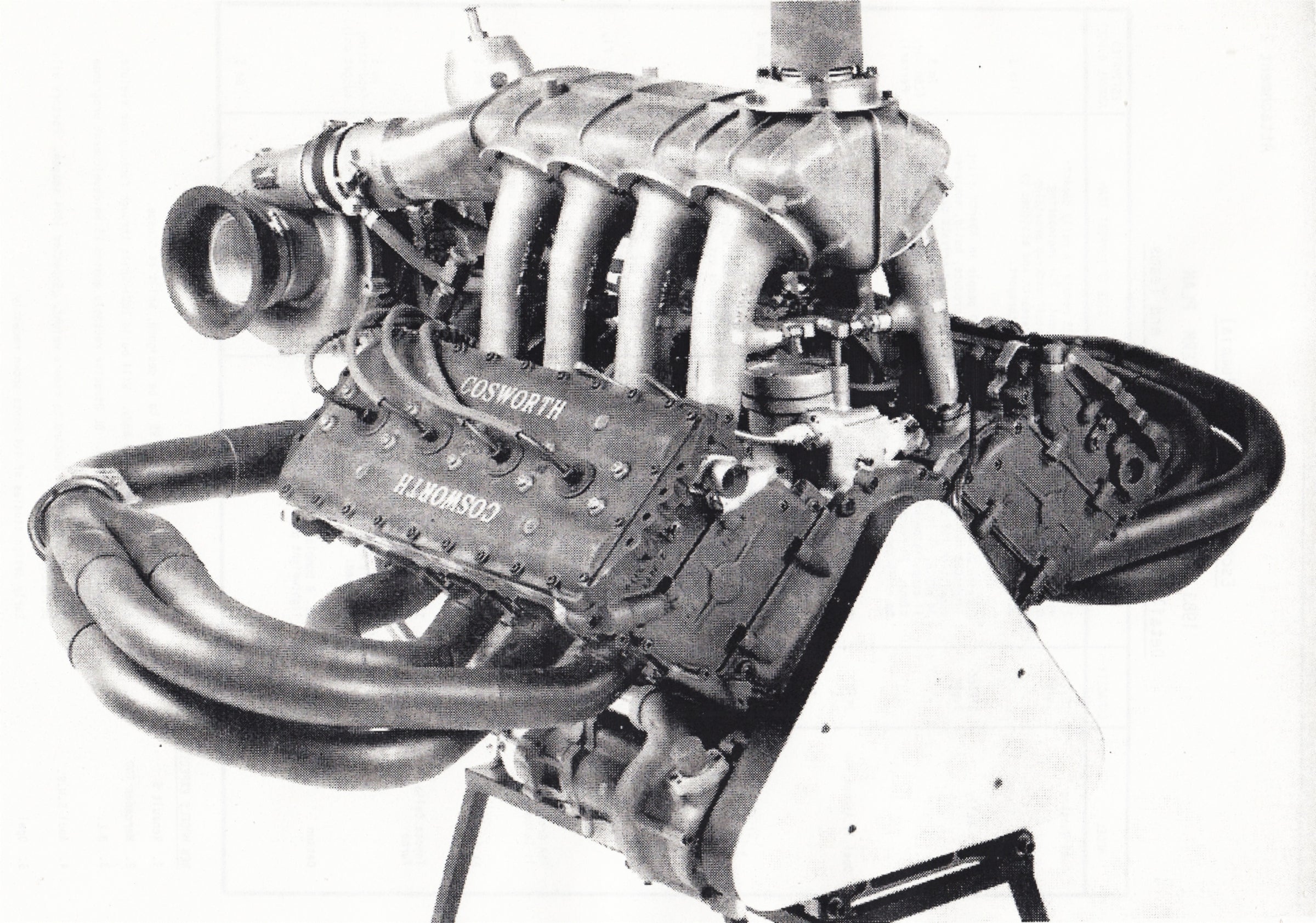

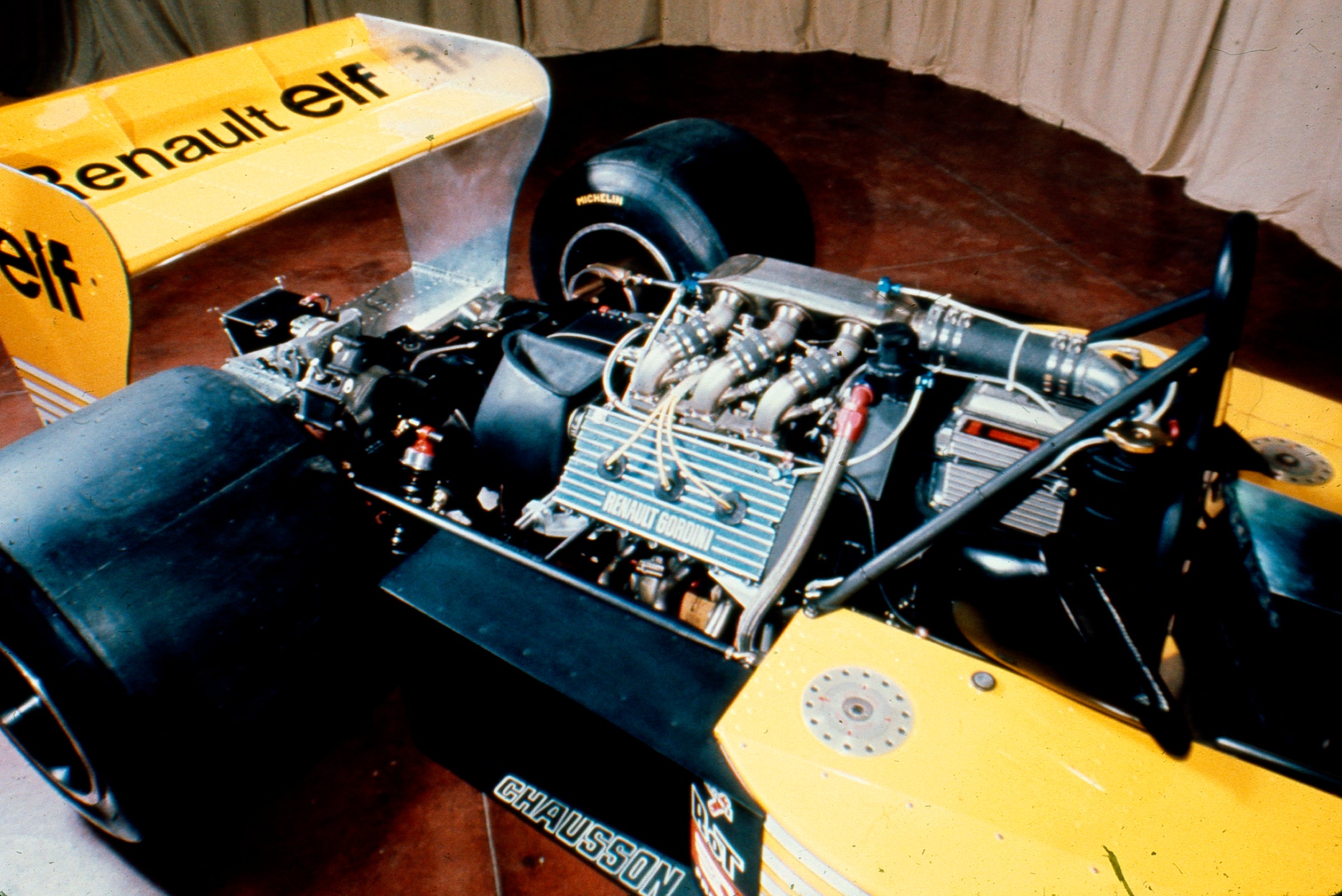

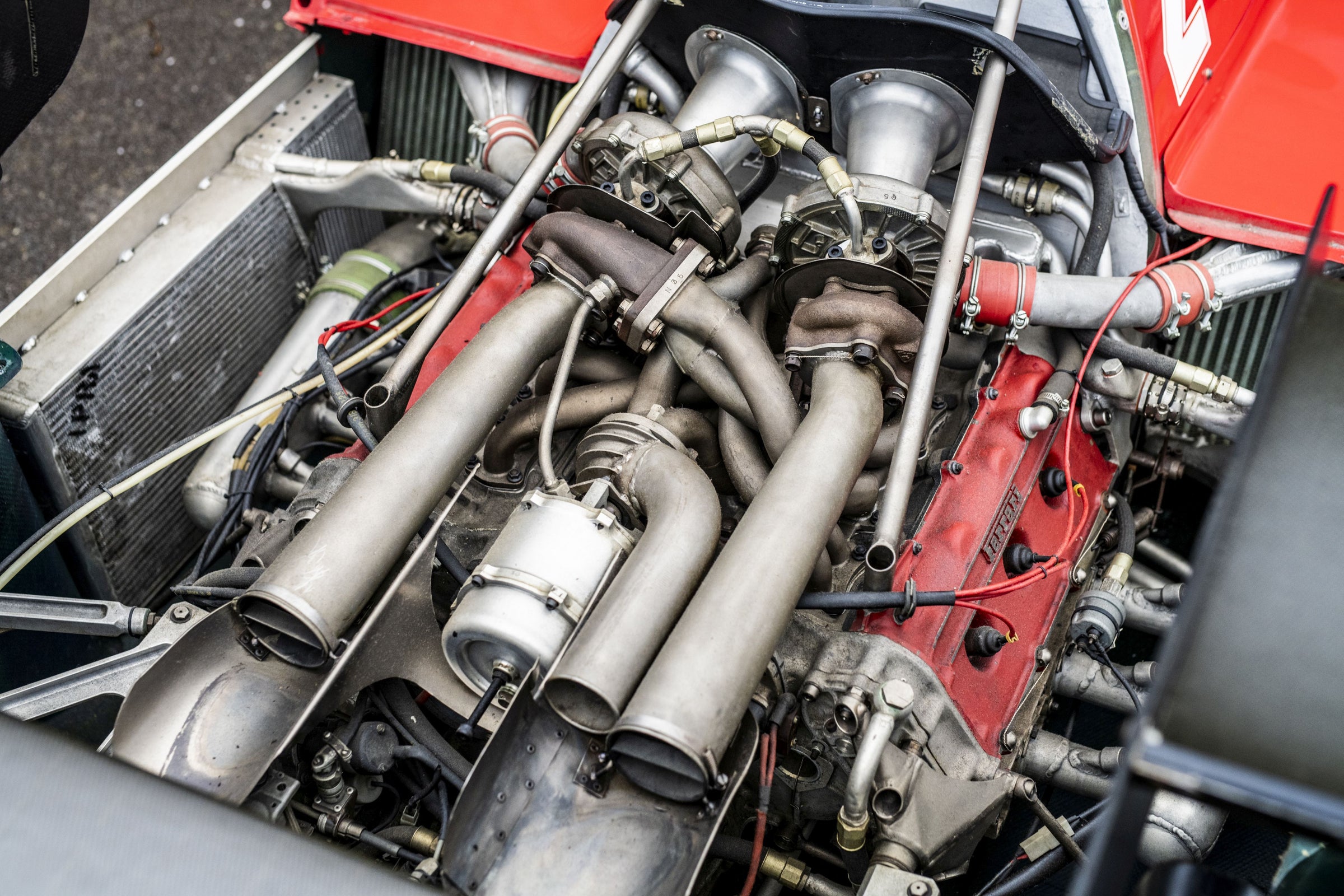

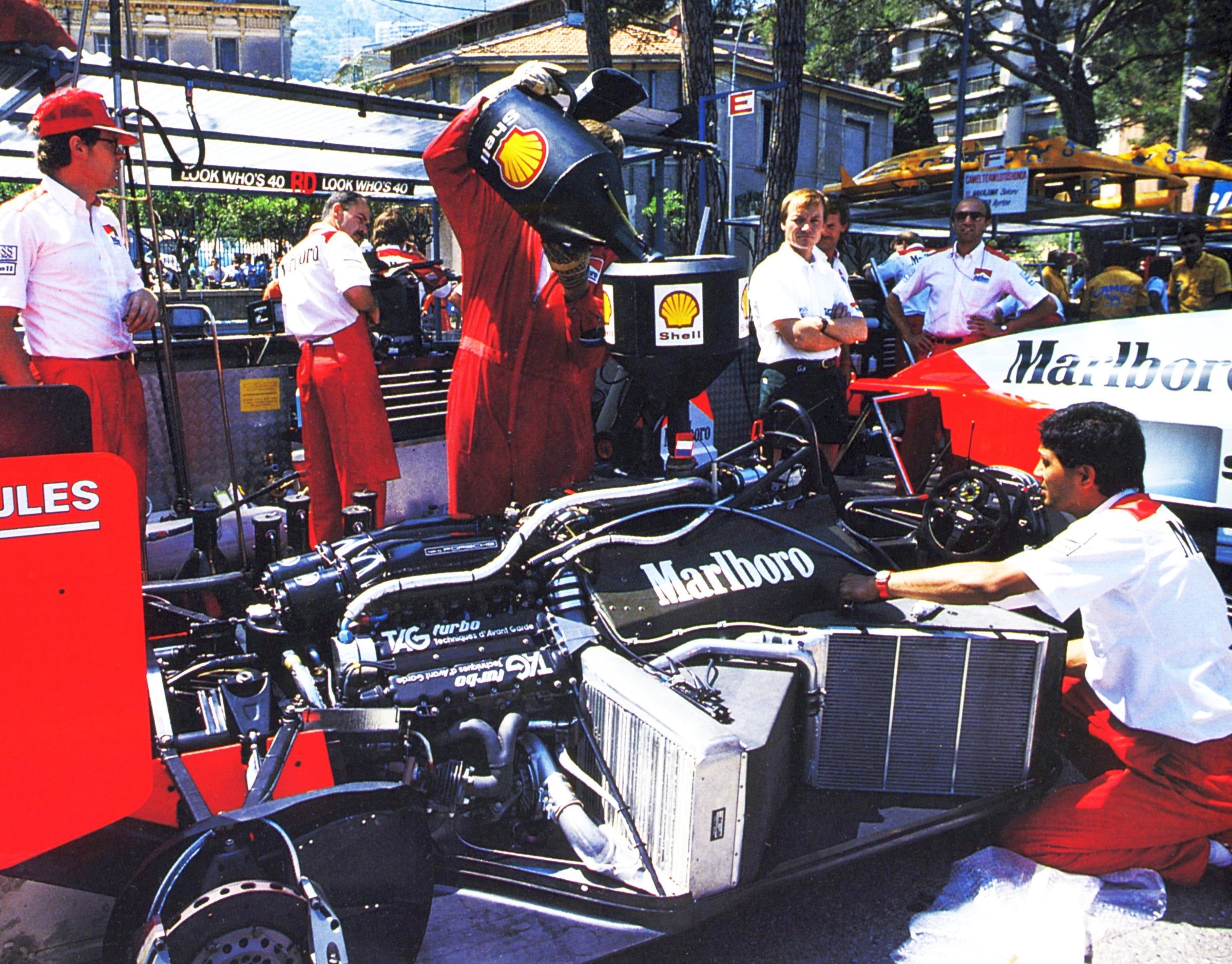

Although the Formula One ratio of 1.5 litres blown to 3.0 unblown since 1966 is attractive, supercharging is not attempted until Renault, after success in sports cars with 2.0-litres blown, gives it a try. Starting in 1977 it is ridiculed until victories come in 1979. Ferrari, BMW-Brabham, Porsche-McLaren and Honda-Williams become successful F.1 turbo users.

At the end of the 1970s auto makers worldwide begin offering turbocharged models. Renault leads with its offerings boosted across the board. In 1982 De Tomaso-owned Maserati introduces the first twin-turbo passenger car, its Biturbo V-6. Japan’s car makers commit to turbocharging, culminating in the creation of brutal anti-lag systems for rallying. ‘Heroes of Turbocharging’ are celebrated with super-powered entries from Audi, Opel/Vauxhall, GMC Truck, Toyota, Nissan, Honda and Bugatti.

Led by Roots-refinement pioneer Eaton, mechanical boosters fight back, welcomed by upmarket auto makers. Fiat defies convention with its Abarth Roots ‘Volumex’. Vane chargers command attention as do exotic orbital concepts from the Wankel playbook. Alf Lysholm’s spiral charger is resurrected in Britain as the ‘Sprintex’ as is the centrifugal’s potential as the ‘Suprex’.

Completely new principles enter the field from Swiss Brown Boveri (BBC) with its exhaust-echoing ‘Comprex’ and Volkswagen with its ingenious scroll-type ‘G-Lader’. ‘Vairex’ is the moniker for a variable-displacement blower from America. Variable-speed centrifugal drives come from Antonov, Torotrak as the ‘V-Charge’ and Integral Powertrain with its ‘SuperGen’. Multi-stage designs marry turbos with mechanical blowers.

Ultimate forced-induction concepts include separate engines to drive compressors, including one from Citroën. Hydraulic and electric drives and boosters proliferate. An oxygen-bearing chemical ignites to drive superchargers! The book ends with a bang!

• Volume 1, ‘Rushing toward the racing zenith, 1890s to 1950s’, begins by introducing the bold pioneers who first won races with blowers in 1910 and then took to the air to gain altitude with supercharging in the Great War.

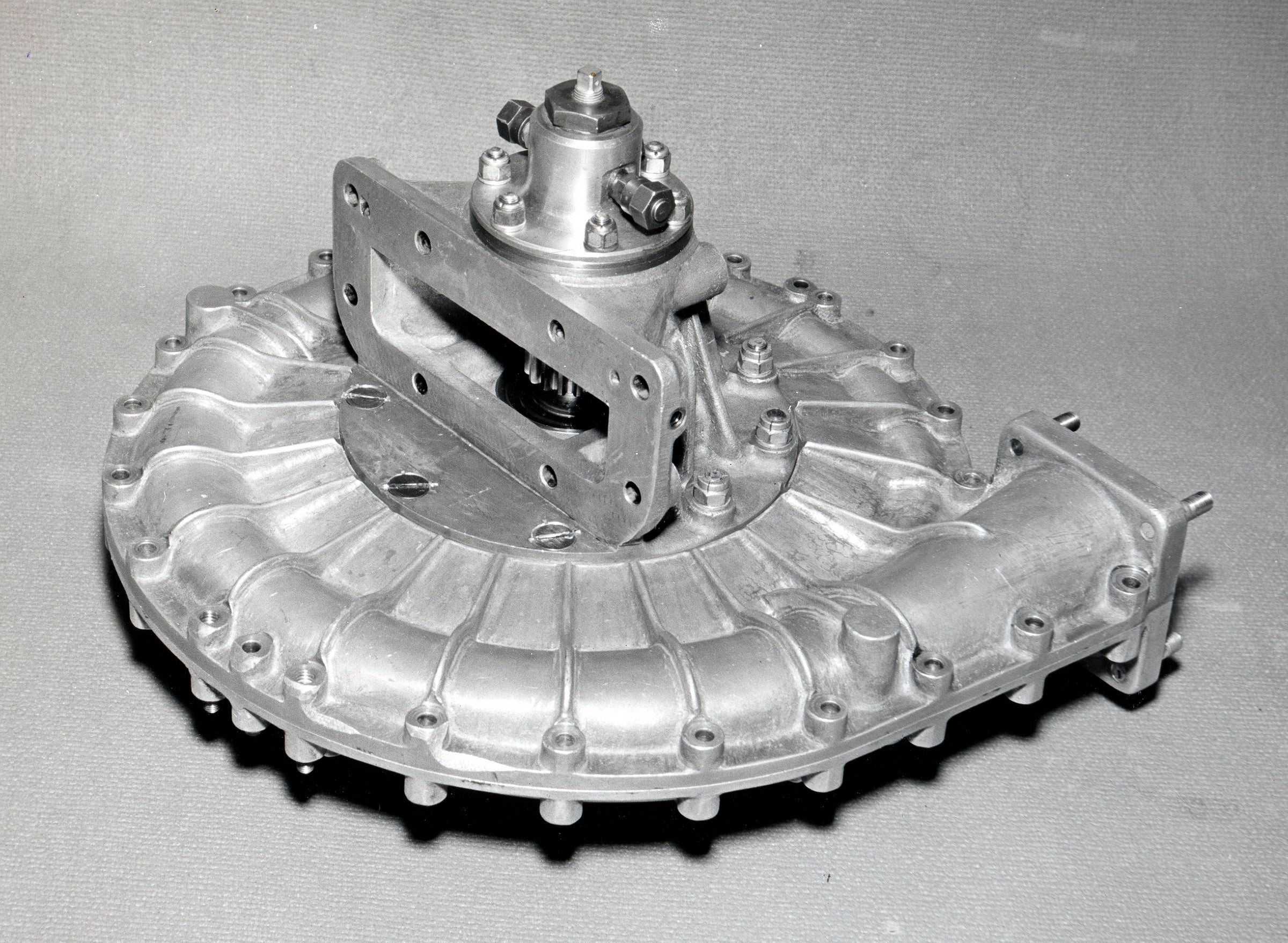

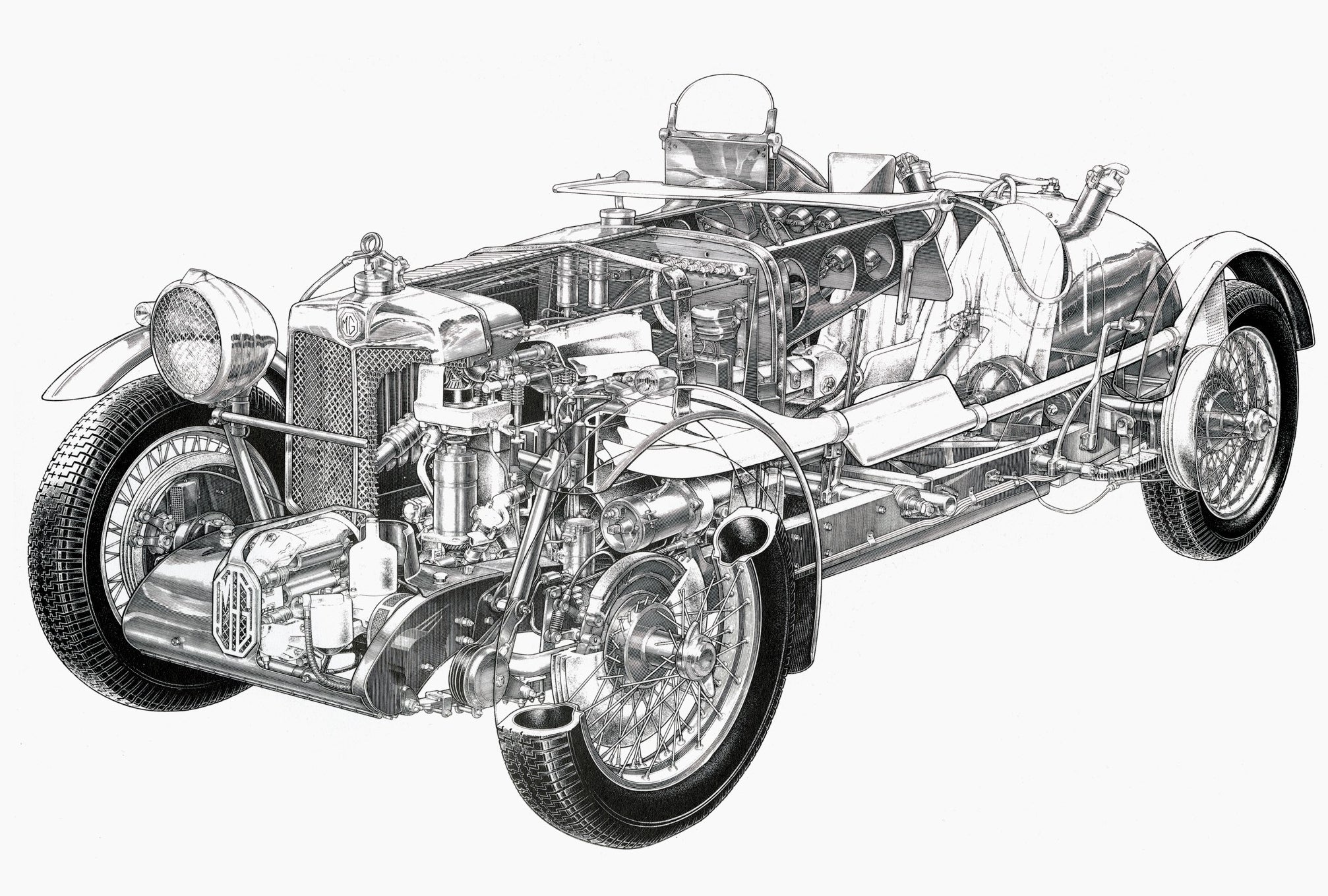

• Inventive ideas for piston-type blowers, Roots-type, centrifugal, screw-type, vane-type, exhaust-driven turbos and other new compressor technologies.

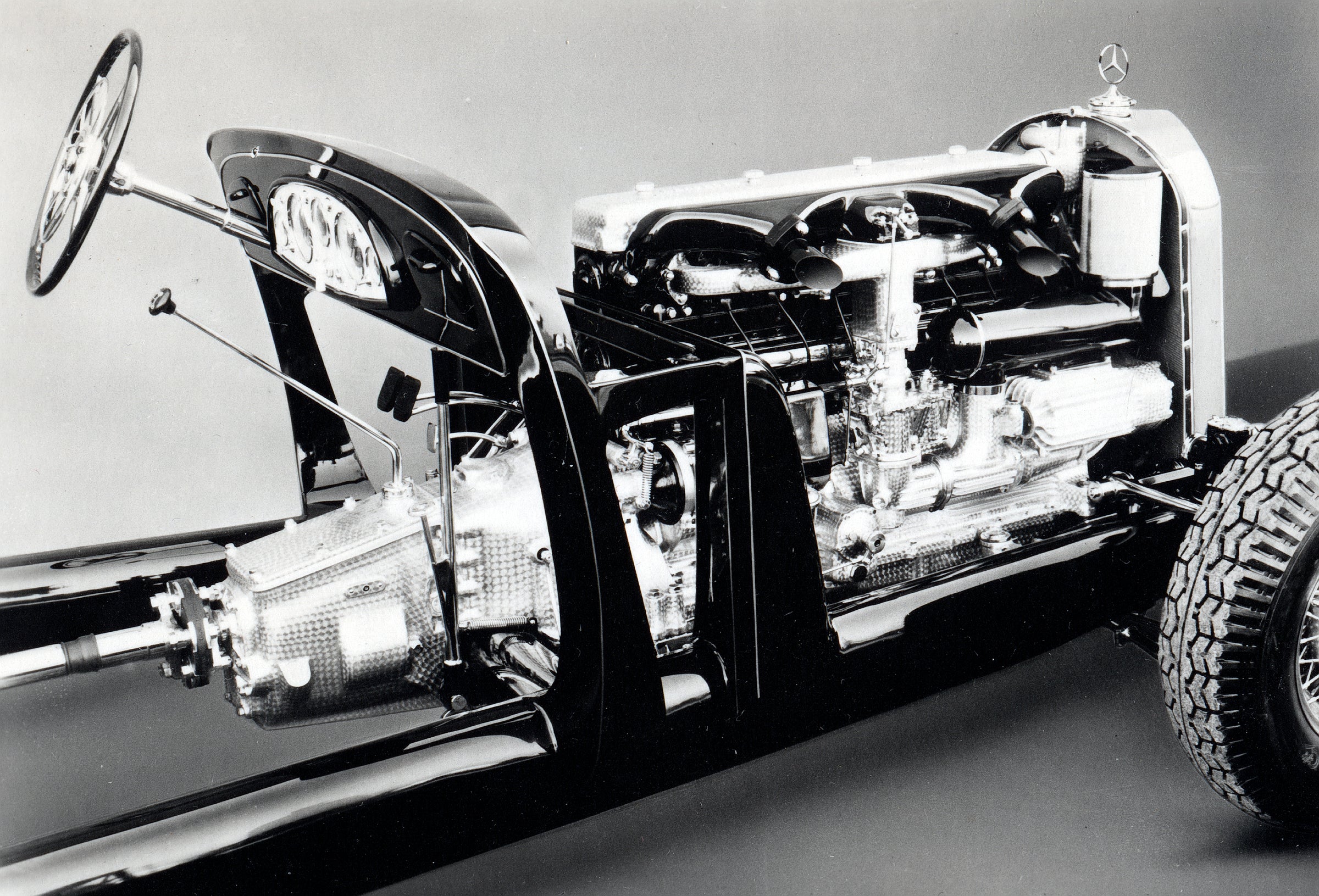

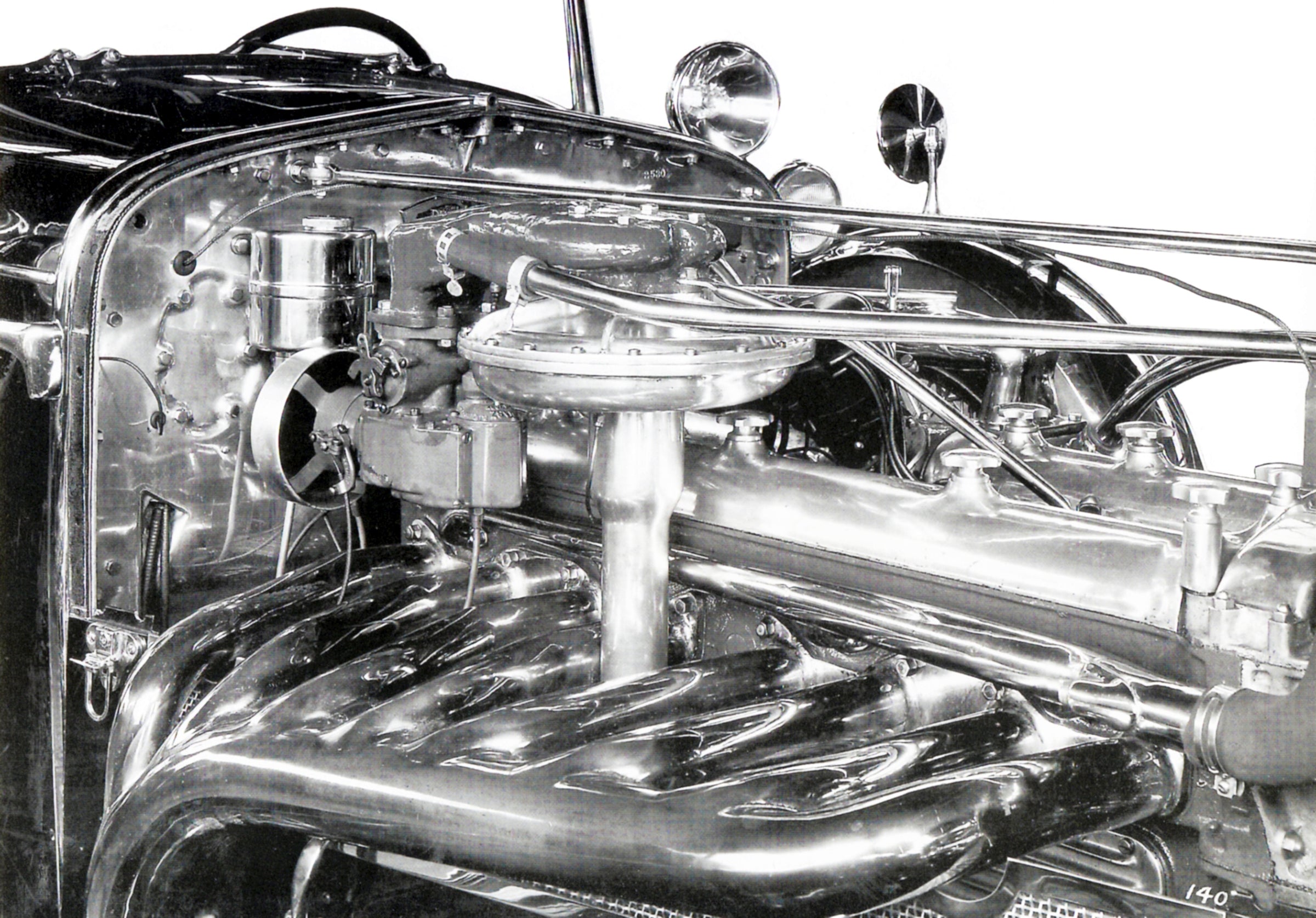

• How Fiat, Mercedes and Duesenberg vied to be first in racing with blowers in the early 1920s, sparking a world-wide swathe of interest in exotic supercharged road and track cars that also embraced the likes of Alfa Romeo, Bentley, MG, Miller, Sunbeam and many more.

• As befits its title, ‘Wartime boost to forced induction, 1930s to 1970s’, Volume 2’s focus is on the huge strides made in supercharging and turbocharging in World War II by Allied and Axis combatants.

• Post-war, America powered ahead with turbocharging’s proliferation in racing at Indianapolis followed by wider use from the 1970s for passenger cars and racers, most notably Formula One’s 1,500-horsepower projectiles.

• Volume 3, ‘Turbo triumphs on road and track, 1970s to 2020s’, introduces the many and varied applications of boosting for petrol and diesel engines through to the present day.

• Why and how the 21st century sees sweeping conversion of both road and racing cars to forced induction for higher efficiency and the ultimate in road-burning performance.

• All told this mighty work contains over 3,500 rare and historic images of superchargers and turbochargers along with their designers and the sensational cars and aircraft that have carried their creations.

Format: 270x210mm

Three jacketed hardbacks in a slipcase

Page extent: 1,960 (individual volumes are 688, 664 and 608 pages)

Illustration: 3,567 photographs and diagrams, including colour

We deliver to addresses throughout the world.

UK Mainland delivery costs (under 2kg) by Royal Mail £5.00.

Books will normally be shipped within two working days of order. Estimated delivery times post shipment. UK: Up to 5 working days. Europe, Northern Ireland and Highlands and Islands: Up to 8 days. USA: Up to 12 days

IMPORTANT NOTICE FOR EU CUSTOMERS: Delivered Duty Unpaid (DDU) means that customers are responsible for paying the destination country's customs charges, duties. Regrettably parcels will sometimes be held by customs until any outstanding payments are made. Any payments not received may result in courier returning or in some cases destroying your books.

Unwanted products can be returned with the original packaging within 14 days of delivery. Returns will be at your own cost.

If you receive a faulty or damaged item please contact orders@evropublishing.com for return and replacement information.