Jacky Ickx

His Authorised Competition History

- In stock, ready to ship

- Inventory on the way

EXTRACT 1

Budapest Grand Prix (H)

Nepliget Park, 20 September 1964, Group 2

Ford Lotus Cortina (BTW 298B) • #23

Qualifying: 4th • Result: 3rd in class

Ickx’s third outing for Alan Mann Racing took place in Hungary and proved to be a defining moment in his career — but he almost didn’t make it to the race. As Hungary was behind the Iron Curtain, a foreign participant required a visa that had to be obtained from the Hungarian Embassy in his own country. Although Ickx’s visa had been ordered in good time, confirmation never arrived in Brussels because the Hungarian authorities mistakenly sent the paperwork to Vienna. It was only when Ickx was able to find a French-speaking telephonist at the Hungarian Automobile Club that the mistake was rectified, and his visa arrived in the nick of time for him to contest the Budapest Grand Prix, the penultimate round of the European Touring Car Challenge.

Despite the long journey and the logistical challenges of racing behind the Iron Curtain, all the works teams were present. Ickx was again required to support John Whitmore’s title challenge and carried out his role to the letter during practice, following his team leader carefully and neatly around the dangerous course, which was a variant of the pre-war parkland circuit, surfaced mainly with paving stones and criss-crossed by tram tracks that pounded suspensions and caused many breakages.

The 1,600cc, 1,300cc and 850cc classes were combined for a single three-hour race. While Whitmore disputed the lead with Hubert Hahne’s BMW 1800TI, Ickx and Peter Lindner (Lotus Cortina) fought a gripping duel, locked together for lap after lap. Lindner was able to keep Jacky behind and finally pulled away until his rear axle — the weak point of the Lotus Cortina Mk1 — failed and the car retired in the pits. Ickx then became embroiled in a battle with Gianni Balzarini’s factory Alfa Romeo Giulia TI and Warwick Banks’s Mini Cooper, which was being run by Ken Tyrrell.

Tyrrell had a keen eye for talent and two incidents in the race gave him the opportunity to witness Ickx’s stoicism in adversity. First, Jacky lost his left-front wheel and arrived at the pits with the brake disc dragging on the road and trailing sparks, but the youngster pulled in without drama and waited calmly on the pit wall while a new wheel was fitted. Some time later, overheated brake drums caused a small rear-end fire during a refuelling stop, but Ickx again remained completely unruffled and sat patiently in his car while the mechanics worked away before rejoining the race with undiminished determination. Tyrrell, watching from the adjoining pit, was impressed.

During the race, Alan Mann also talked to Tyrrell about Ickx and said that he thought the 19-year-old needed to be in single-seaters. Ickx later recalled: ‘Ken came up to me at the finish line. He was tall and had a wild, determined smile on his face. I was reserved in such company, almost shy. Ken asked me if I wanted to try a Formula 3 single-seater. I politely declined the offer and said that my impending military service didn’t give me much time, but he wrote down my contact details and my parents’ address and insisted that we stay in touch.’ At the airport the following day, he again encountered Tyrrell, who reiterated his opinion that Ickx should try an F3 car as soon as possible.

As for the rest of the gruelling Budapest Grand Prix, Hahne beat Whitmore by a lap while Ickx finished 13th overall and third in class after the delays, having completed just 89 laps compared with the winner’s 103.

EXTRACT 2

Spa 1,000Km (B)

Spa-Francorchamps, 1 May 1967, Group 4

Mirage M1-Ford (M10003) • #6 (shared with Alan Rees/Dick Thompson)

Qualifying: 2nd • Result: 1st

The fact that all the top sports-car teams were ready to contest another 1,000Km race just six days after Monza, on a Monday, spoke volumes for their preparation and organisation. A third Mirage chassis had been built for the lead pairing of Ickx/Rees, with a new 5.7-litre Ford V8 prepared by Holman Moody giving some 400bhp. While this engine didn’t make their Mirage any faster along the Masta straight than the sister car of Piper/Thompson, it had noticeably more torque and was quicker on the uphill section from Stavelot to La Source. The car was only completed the day before practice and ran faultlessly.

Practice on Saturday took place in good weather. With many of the leading drivers competing in the F1 International Trophy at Silverstone, the Hill/Spence Chaparral was the immediate pacesetter ahead of Ickx, these two alone breaking the 3m 40s barrier. When the rest of the drivers arrived on Sunday morning, the Chaparral didn’t improve its time but Ickx went 0.5sec quicker to confirm his second place on the grid. It was a measure of Jacky’s mastery that the other Mirage, sixth on the grid, was 10.4sec slower.

Steady rain fell throughout Monday morning and the 29-car field prepared for a wet race. Ickx shot into an immediate lead with the Équipe Nationale Belge Ferrari of Willy Mairesse/‘Beurlys’ (Jean Blaton) right behind. That was as close as anyone got all afternoon. A little over four minutes later, the Mirage plunged past the pits, through Eau Rouge and disappeared out of sight towards Les Combes before the next car arrived on the back straight behind the pits. The bemused announcer and the spectators in the stands opposite the pits thought there must have been an accident that had delayed the others, but no.

With a clear but wet road in front of him, Ickx built up a huge lead over Mairesse, who in turn left all other pursuers far behind as he tried fruitlessly to keep his young compatriot in sight. For the moment, the only issue for the respective team managements at JWAE and ENB, with refuelling stops and driver changes looming, was the knowledge that the co-drivers of the two leading cars would struggle to maintain this pace. After 20 laps, the rain eased and Mairesse made slight inroads into Ickx’s lead. Jacky finally pitted for fuel after 26 laps, whereupon team manager David Yorke sent him back out to resume his dominant drive. Mairesse, having led for a lap, stopped next time round and ‘Beurlys’ took over the yellow Ferrari. As ENB’s pit work was a little quicker, ‘Beurlys’ rejoined in the lead, but Ickx, driving at undiminished pace, soon passed the Ferrari and simply drove away into the distance again.

The unwelcome realisation now dawned on Rees that he was not, as he had previously thought, Mirage’s number one driver. Unhappy that Ickx had been chosen to start the race, he was equally disenchanted that the Belgian was clearly Yorke’s favourite. Rees made his feelings known before deciding to leave the track, effectively quitting the team there and then. Fortunately, Thompson could take Rees’s place because he hadn’t driven the other Mirage, Piper having crashed it due to a shock-absorber breakage after only seven laps. The regulations specified that no driver could race for more than three hours without relief; with the three-hour mark fast approaching, Thompson would soon have to take over.

Ickx lapped ‘Beurlys’ on lap 38, shortly before the Ferrari made its next pitstop, and as Mairesse left the pits, Yorke prepared to call Ickx in. Trouble was, Thompson couldn’t immediately be found; he was eventually located in the paddock preparing to leave the circuit, believing that he was no longer needed. Ickx was forced to continue until Thompson was ready to take over and that meant he exceeded the three-hour maximum. The Mirage should have been penalised a lap, but Wyer and Yorke played a rather dubious card, arguing with race director Leon Sven that there had been extenuating circumstances. They threatened to bring Thompson back in immediately if a penalty was awarded but promised to leave him in the car for the obligatory hour if it was rescinded. A flustered Sven agreed that a penalty would only be imposed if there was a protest from another team, but none came and so the ploy worked. Porsche, deeply impressed by Ickx’s performance and committed to its own sense of sportsmanship, refrained from protesting.

Meanwhile, Thompson circulated some 30 seconds per lap down on Ickx’s pace but nonetheless retained the lead throughout his stint before handing the car back on lap 58. Ironically, all the politicking proved unnecessary as Mairesse spun off and crashed in the streaming conditions on his first lap after taking over, leaving the Mirage completely unchallenged. All Ickx needed to do was to keep going for the final 13 laps to take the win, although he didn’t slacken off much, continuing to average over 120mph (193kph) in the steady rain.

On the Mirage’s second outing, and only his sixth race in a sports prototype, he finished a lap ahead of the Hans Herrmann/Jo Siffert Porsche 910. An attempt by Ford to claim the points was rejected by the FIA, as ‘Ford’ wasn’t mentioned on the entry, merely ‘Gulf Mirage’. Any suggestion that the Mirage’s speed was due to a tyre advantage was disproved by the fact that it wore the same new Firestone rain tyres as the pole-position Chaparral.

EXTRACT 3

French Grand Prix

Rouen-Les Essarts, 7 July 1968, F1

Ferrari 312 (0009) • #26

Qualifying: 3rd • Result: 1st

With the limitations of a public-road circuit there was no Saturday practice at Rouen, so qualifying was held on Thursday and Friday afternoons. The first session lasted only 50min, which annoyed the F1 drivers, particularly when the junior formula pilots carried on until nightfall. Ferrari had the same three cars as at Zandvoort but fitted with two air scoops on the roll-over bar to cool the central exhaust manifold. Ickx’s time from Thursday, when he had been second quickest, was good enough to put him third on the grid, on the outside of the front row. There was a final untimed session early on Sunday even though the start of the race wasn’t until 4pm. Just before it, the drivers were chauffeured on a parade lap by senior team personnel in Matra coupés, Forghieri driving lckx.

Rain was predicted and until the very last minute no-one was certain about which tyres to fit. Having noticed the gathering dark clouds that reminded him of those he knew so well from Spa, Ickx was the only driver to take the start on full rain tyres and found himself poised to take full advantage. Bad marshalling and poor flag control resulted in a very messy start as the 16 cars slithered away in a ragged formation. Jackie Stewart’s Matra led down to the Nouveau Monde hairpin, after which Ickx swept past him and began to pull away.

As the leaders finished their third lap, they were unaware of the violent, fiery accident behind them involving Jo Schlesser’s Honda, but as they plunged down the hill through Six Frères they were confronted by a wall of flame from burning fuel spreading across the track. At this stage Ickx led by 3sec but he was forced to slow as he picked his way through the smoke and debris of the accident scene, where Schlesser had had no chance of survival. For the next few laps it was chaos, with ambulances, firemen and marshals on the track. As everyone took things more carefully, John Surtees (Honda) and Pedro Rodríguez (BRM) closed up on the leading Ferrari. These three were running nose-to-tail on lap 5, but once the aftermath of the accident had been cleared Ickx pulled away again and by lap 10 he led Rodríguez by almost 7sec.

Next time round Ickx lapped the Matra of Jean-Pierre Beltoise, who was clearly on the wrong tyres, and steadily began to haul in more cars. With his Ferrari properly shod and relishing Rouen’s fast sweeps — not dissimilar to those of his beloved Spa-Francorchamps — his driving in the wet was in marked contrast to his rather tentative performance at Zandvoort two weeks previously. The rain set in with a vengeance at around lap 19, with severe squalls blowing across the track. During this spell Ickx had a ‘moment’ on the ascent at the back of the circuit and both Rodríguez and Surtees managed to get ahead of him, but not for long. As they came past the pits and down the hill, the Ferrari’s better traction showed and Ickx firmly retook the lead. Despite a vicious, snaking slide as he crossed the white-painted lines of the dummy grid, within just two laps his margin was 17sec, and after two more laps it was 35sec. Rodríguez and Surtees had no response and by half-distance his advantage over them was more than 1min.

Despite this huge lead, Ickx — averaging 100mph (160kph) in the monsoon conditions — didn’t let up and by lap 42 he had lapped third-placed Surtees and now led Rodríguez by over 2min. Only when the BRM driver was suddenly slowed by a sticking gearchange did Ickx finally ease off, allowing Surtees to unlap himself. With ten laps remaining, the sun emerged again and the track slowly started to dry. Ickx could now coast to the finish and took the flag just a whisker under 2min ahead of second-placed Surtees.

Ickx scored his first Grand Prix win in consummate style, having led virtually throughout. Once again he had shown his mastery in appalling conditions but was the first to acknowledge the lessons that the earliest days of his career had taught him, telling Le Soir: ‘I competed in trials in winter for five seasons. This sport is practised on snow, ice, mud; the bike always slides. It taught me how to find grip. A trials motorcycle is ridden with velvet fingers, infinite softness. In addition, I had an intuition to fit wet tyres while everyone was starting on dry tyres. The rain began as soon as the race started and I won because I didn’t make any mistakes.’

EXTRACT 4

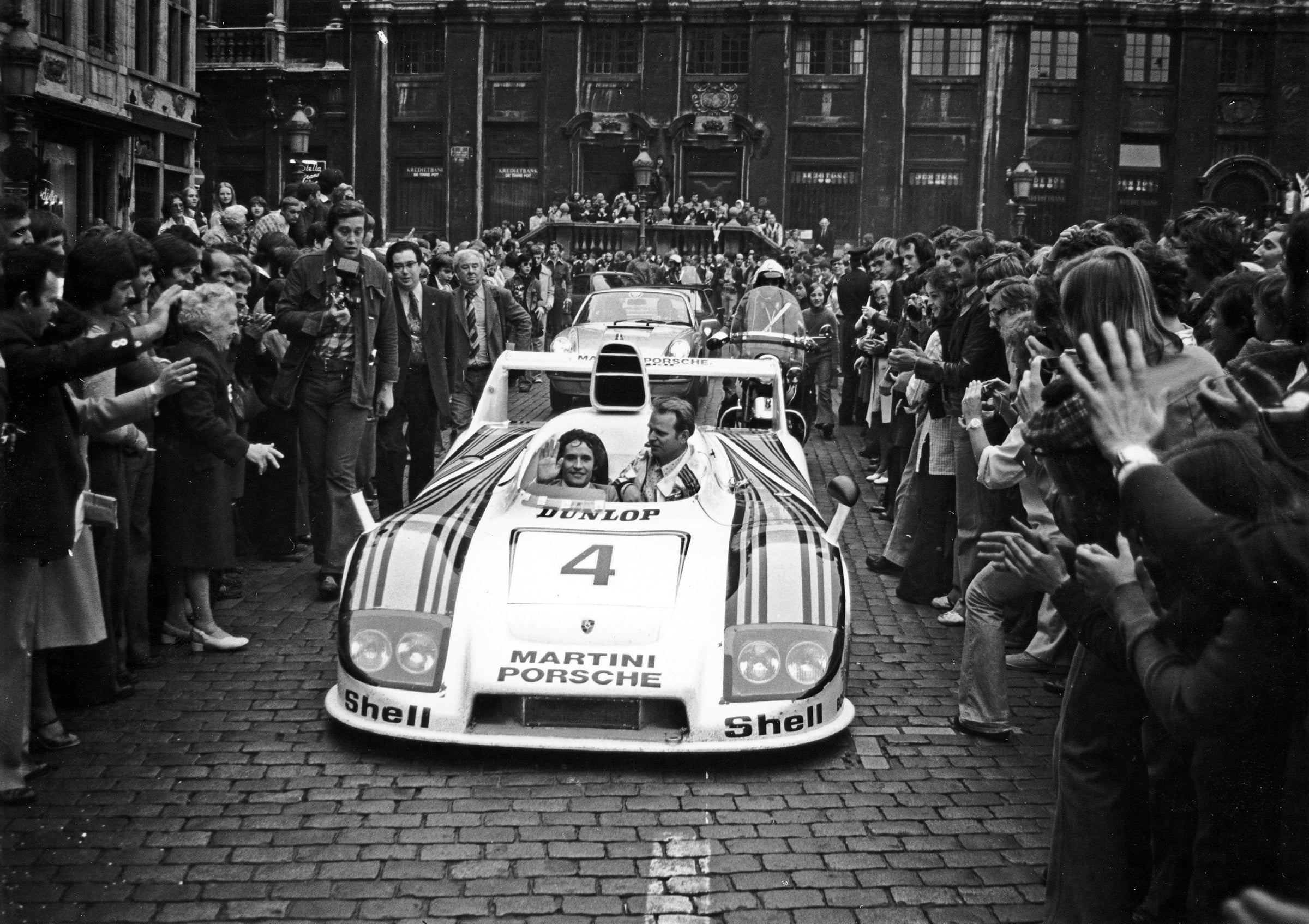

Le Mans 24 Hours (F)

Le Mans, 11–12 June 1977, Group 6

Porsche 936/77 (002) • #3 (shared with Henri Pescarolo)

Porsche 936/77 (001) • #4 (shared with Jürgen Barth/Hurley Haywood)

Qualifying: 3rd • Result: #3, DNF (engine); #4, 1st (fastest lap)

With Renault out for revenge, the Le Mans 24 Hours saw a huge confrontation between the French manufacturer and Porsche. The Alpine-Renault team had concentrated its entire Group 6 programme on Le Mans and sent four long-tail A442s with a fabulous driver line-up comprising Jean-Pierre Jabouille/Derek Bell, Jacques Laffite/Patrick Depailler, Patrick Tambay/Jean-Pierre Jaussaud and René Arnoux/Didier Pironi. Porsche faced them down with two 936/77s, pairing Ickx with fellow three-time winner Henri Pescarolo in its #3 car and Jürgen Barth with Hurley Haywood in #4. The Porsches were the same chassis that had run at Le Mans in 1976, albeit with extensively modified bodywork and engines. The French cars duly took four of the top five grid positions, split by third-placed Ickx.

The 4pm start saw Jabouille take command but the French assault faltered only halfway round the lap when Pironi stopped his car at the end of the Hunaudières straight with loss of oil from a split pipe. After half an hour, the 936/77s of Ickx and Barth lay second and third, with Jabouille now 25sec ahead. The Porsches had much greater range than the Alpine-Renaults, so when Jabouille stopped after only 18 laps to refuel and hand over to Bell, Ickx briefly assumed the lead, relinquishing it again when he made his refuelling stop five laps later and Pescarolo took over. The same thing happened at the next round of Alpine-Renault pitstops, except that Pescarolo’s spell in the lead was more tenuous because Bell was nearly 1min to the fore when he stopped on lap 39 and handed back to Jabouille.

After only three laps, Jabouille was back in front again and second-placed Pescarolo’s own pitstop was now imminent — except he didn’t get that far. Approaching Arnage on lap 44, he over-revved the Porsche’s engine and it expired in a cloud of oil smoke. With less than four hours gone, Alpine-Renault occupied the top three places.

By this time, Barth/Haywood had suffered two delays, first with 20min lost for a change of fuel pump, then a further 30min with a blown head gasket. After that second calamity, their car had dropped to 41st place, 15 laps down, and now it lay 15th. This was clearly the moment for team manager Manfred Jantke to play his trump card and transfer Ickx to the surviving 936/77 with orders to push. What followed was one of the greatest drives ever seen at Le Mans.

For the next 20 hours, the three Porsche drivers went flat out, scything through the field with Ickx taking the lion’s share of time at the wheel. Through the night, he transcended even his own normal levels of excellence. He drove for hour after hour, completing triple stints and resting for only two brief spells while his co-drivers each did a single stint. He shattered the lap record three times to leave it 2.8sec below the previous best recorded by François Cevert’s Matra in 1973. Barth and Haywood were acutely aware of the magnitude of their newly acquired co-driver’s performance, and Ickx commented later: ‘It was good to see the impact on the team as we climbed up the classification, place by place.’

Despite rain and fog, the 936 reached sixth place by 10pm, fifth by midnight and fourth by 1am, now with just the three Alpine-Renaults ahead. A little before 3am came the first Renault engine failure, eliminating third-placed Tambay/Jaussaud. About 90min later, Depailler pitted to have the second-placed car’s gearbox rebuilt and by the time it could rejoin the Porsche had swept past into second place, six laps behind Jabouille/Bell. The Alpine-Renault drivers were able to hold the gap fairly steady but the three-man Porsche squad kept up the pressure, forcing the pace even if they couldn’t close in. Then, shortly after 9am, Jabouille arrived in the pitlane trailing ominous clouds of smoke, and after one more slow lap the car that had led virtually throughout was retired with piston failure.

Ickx, Barth and Haywood now led but couldn’t relax. Just two laps behind, Depailler/Laffite were chasing hard in the single surviving Alpine-Renault, but French hopes were finally dashed when its engine blew up approaching Arnage with just over four hours to go. Having been 15 laps behind the race leader, the Porsche was now 19 laps ahead of the car that had taken over second place, the delayed Mirage of Vern Schuppan/Jean-Pierre Jarier.

A comfortable victory beckoned — but high drama was still to come. With 45min remaining, the 936 began to emit smoke along the Hunaudières straight. Haywood headed slowly for the pits where the mechanics quickly identified that a piston had burned out. The 936/77 still had an advantage of 17 laps — at least an hour in terms of time — over the Mirage but it couldn’t win the race sitting in the pits. While the mechanics disconnected the valve gear on the offending cylinder and turned the turbo boost right down, Jantke took the decision to hold the car in the pits until the very end of the race. To be classified as a finisher, the regulations required a car to complete its last lap within a given percentage of its penultimate one, so two final laps were required. The task was entrusted to Barth, the highly respected engineer-driver who ran Porsche’s customer motorsport department. He set off at 3.50pm, running on five cylinders and with a huge stopwatch taped to the dashboard so that he could regulate his speed. He carried out his role to perfection, crossing the line 11 laps ahead of the Mirage.

Ickx, Barth and Haywood became the first three-driver line-up to win Le Mans. As for Ickx, this was fourth victory, a feat previously only achieved by one man, Olivier Gendebien, a fellow Belgian who was present to witness the moment. Many years later, Jacky judged the race to be the finest of his career. His exertions in driving the winning car for 11 hours, mostly in darkness except for a single shift on Sunday morning, caused a loss of 5kg (11lb) in his body weight and left him utterly exhausted. Reflecting on Jacky’s extraordinary efforts through the night, including his annihilation of the lap record, Haywood commented: ‘That was phenomenal… one of the greatest drives ever.’

By Jon Saltinstall

Preface by Jacky Ickx

Foreword by Derek Bell

This exhaustively researched book has been written with his full co-operation and outlines every one of the 565 races that he contested in cars and on motorcycles, forming a detailed and insightful record of his racing life supported by over 850 photographs, many of which have never been published before. This is a racing driver’s biography of exceptional depth that all motorsport enthusiasts will treasure.

Starting in motorcycle trials, Ickx was twice crowned Belgian champion before switching to four wheels; he immediately proved himself a winner in touring cars and single-seaters, becoming European Formula 2 Champion in 1967.

From 1967, he established himself as a star in sports cars, driving blue-and-orange Gulf Mirages and Ford GT40s to numerous successes, culminating in his first Le Mans victory in 1969 with its famously close finish.

Snapped up by Ferrari for 1968, he achieved a heroic first Formula 1 victory in that year’s rain-soaked French Grand Prix, confirming his career-long reputation for peerless driving in wet weather.

Other than one season with Brabham, Ickx spent his best Formula 1 years with Ferrari, achieving eight wins in the period 1968–72, and twice finishing second in the World Championship standings, with Brabham (1969) and Ferrari (1970).

Post-Ferrari, his Formula 1 fortunes waned but he thrived in sports cars, claiming three successive Le Mans victories, with Mirage in 1975, then with Porsche.

After his fifth Le Mans win in 1981, the rebirth of sports car racing in the Group C era from 1982 saw Ickx as anchorman in the all-conquering works Porsche team, a four-year period that brought his record sixth Le Mans victory, 12 wins in total, and two World Champion titles.

After retirement from circuit racing, his later career took him into entirely different motorsport adventures in rally raids, where his Paris–Dakar record includes victory in 1983 (driving a Mercedes-Benz) and second places in 1986 (Porsche) and 1989 (Peugeot).

Format: 280x235mm

Hardback

Page extent: 608pp

Illustration: 900 photos, including much colour

We deliver to addresses throughout the world.

UK Mainland delivery costs (under 2kg) by Royal Mail £5.00.

Books will normally be shipped within two working days of order. Estimated delivery times post shipment. UK: Up to 5 working days. Europe, Northern Ireland and Highlands and Islands: Up to 8 days. USA: Up to 12 days

IMPORTANT NOTICE FOR EU CUSTOMERS: Delivered Duty Unpaid (DDU) means that customers are responsible for paying the destination country's customs charges, duties. Regrettably parcels will sometimes be held by customs until any outstanding payments are made. Any payments not received may result in courier returning or in some cases destroying your books.

Unwanted products can be returned with the original packaging within 14 days of delivery. Returns will be at your own cost.

If you receive a faulty or damaged item please contact orders@evropublishing.com for return and replacement information.