Le Mans 2000–09

The official history of the world's greatest motor race

- This item will be available in June 2025

2000

AUDI: VENI, VIDI, VICI…

ENTRY

At the head of the field there was almost a complete change from the participants in the 1999 race. BMW and Toyota were bound for the ‘Promised Land’ of Formula 1. Mercedes-Benz had made a hasty retreat from endurance racing, a consequence of its aerobatic antics at La Sarthe. Nissan had found itself in dire financial straits, forced to close three factories in Japan with substantial redundancies. Porsche had changed its motorsport strategy at the last minute, abandoning its LMP2000 project and concentrating its efforts on supporting customer GT racing.

The vacuum created by these withdrawals was filled by Detroit giants taking a sudden interest in long-distance racing, fuelled no doubt by the successful inaugural season of the American Le Mans Series. Chrysler and Cadillac each commissioned a three-year programme aimed at outright victory at Le Mans, while Corvette stepped up to challenge Viper and Porsche in the LM GTS class. Not since George Patton’s Third Army had swung through Le Mans back in August 1944 had La Sarthe witnessed such a diverse range of American firepower.

The American contingent numbered 19, including no fewer than five Panoz LMP 1 Roadsters and four Cadillacs. They would need all available ammunition because Audi was back at Le Mans, determined to prove that it had absorbed the lessons of its début performance the previous year. Audi’s new R8 had been dominant at Sebring earlier in 2000 and the cars were clear favourites for victory.

Over 100 entries were submitted to the Automobile Club de l’Ouest, but the ACO Selection Committee’s deliberations reduced the number to a more manageable level. Preliminary practice, held on 30 April, saw 58 invited cars take part, chasing the 48 spots on the grid, but five cars were withdrawn before the event. Local hero Courage Compétition, a participant since 1982, was an innocent casualty of Nissan’s financial catastrophe. TV Ashai’s decision to confine its sponsorship to two Panoz entries caused Hugh Chamberlain to pull his second Viper.

In a change from previous years, the sessions were not officially timed, apparently on the advice of the FIA, so the ACO Selection Committee would decide the unlucky five that would have to miss the race. Another change from previous years was splitting the prototypes and GTs into two groups, each of which had two hours on track in the morning and afternoon.

The first casualty was Manthey Porsche, which had received two automatic entries due to winning the LM GT class at Le Mans and Petit Le Mans in 1999. The team passed one invitation to Weiland Automotive Team, but the car presented for initial scrutineering was said to be a 996 Supercup model, and therefore its technical passport was invalid, so it was not allowed to participate.

Three cars failed to record a competitive time. The Ascari A 410 suffered transmission problems that could not be remedied; the team developed a new unit, but it was not ready in time. The Debora LMP299 of Pierre Bruneau lost a wheel during the afternoon and was not considered to be competitive. Having failed to pre-qualify in the previous four years, Gerard MacQuillan pinned his hopes on his Harrier LR10, but hired-gun Gary Ayles did not manage to set a time as the car’s engine expired on his first flying lap. The second Roock Porsche 993 GT2 R, by now outdated, was the slowest of the LM GTS class and was also turned away.

When the final list was released, there were 20 entries invited to compete in LM P900 with a further six in the new LM P675 class. The LM GTS contingent featured ten cars, while Porsche had a monopoly in LM GT with all 12 contestants running the latest 996 GT3 R model.

Several familiar names were missing. Henri Pescarolo now confined himself to a role as team principal after 33 participations and four outright victories. Pierre Yver, who had an unbroken run of races dating back to 1982, with second place overall in 1987 to his credit, also called time on his driving career. Budgetary issues meant there was no entry from Kremer Racing, which had been part of the spectacle since 1970, most memorably winning in 1979 with its Porsche 935 K3.

QUALIFYING

Predictions that the Audi steamroller would flatten the opposition proved to be correct and the battle for the front row boiled down to a contest between Allan McNish and Tom Kristensen, with the Scot shading his Danish team-mate by just half a second. Rinaldo ‘Dindo’ Capello in the other Audi R8 was a similar margin back in third place.

Leading the charge against the Audi trio was David Brabham in the works Panoz, managing to break the 3:40 barrier fractions ahead of Domenico Schiattarella in the Team Rafanelli Lola and the S.M.G. Courage of Philippe Gache.

In LM P675 the top spot was the property of Jean-Christophe Bouillon’s VW-powered Reynard, just fractionally ahead of team-mate Ralf Kelleners; their ability to turn up the turbo boost meant that their rivals had no answer to their pace. The ROC Reynard pair were some six seconds ahead of the next in class, the W.R. of Xavier Pompidou.

The Viper of Karl Wendlinger grabbed top spot in LM GTS but the challenge from Corvette was amply illustrated by its annexing of second and third spots ahead of the other two factory Vipers.

The LM GT pole seemed to be the property of the Dick Barbour Racing Porsche until Christophe Bouchut wrung the neck of his Larbre Compétition 996 GT3 R on Thursday evening to outpace his rivals by three tenths of a second.

RACE

Like the ambient temperature, a reported high of 31°C, the Audis were red hot from the opening lap, Allan McNish leading from Frank Biela and Michele Alboreto with David Brabham’s Panoz hanging on gamely, the rest of the field being dropped by the time the quartet had reached Tertre Rouge.

The American challenge got off to a disastrous start with the Reynard of Yannick Dalmas suffering engine failure on the first lap. Then Emmanuel Collard’s Cadillac was immersed in flames, after a presumed oil leak. The safety cars were sent out and some teams tried to gain an advantage by pitting. The Panoz outfit, whether by strategy or luck, managed to jump the Audis and Brabham emerged from the pits at the head of the field with McNish claiming that he had been held up by a Viper. The intervention of race control lasted 40 minutes, with the result that a front-engined car led at the one-hour point for the first time since 1963.

Racing resumed and McNish immediately proceeded to chase down Brabham, but the Australian used all his considerable racecraft to stay ahead. Eventually he had to concede and a lap later Alboreto in the second Audi also passed the Panoz. That was the high-water mark for the American roadsters.

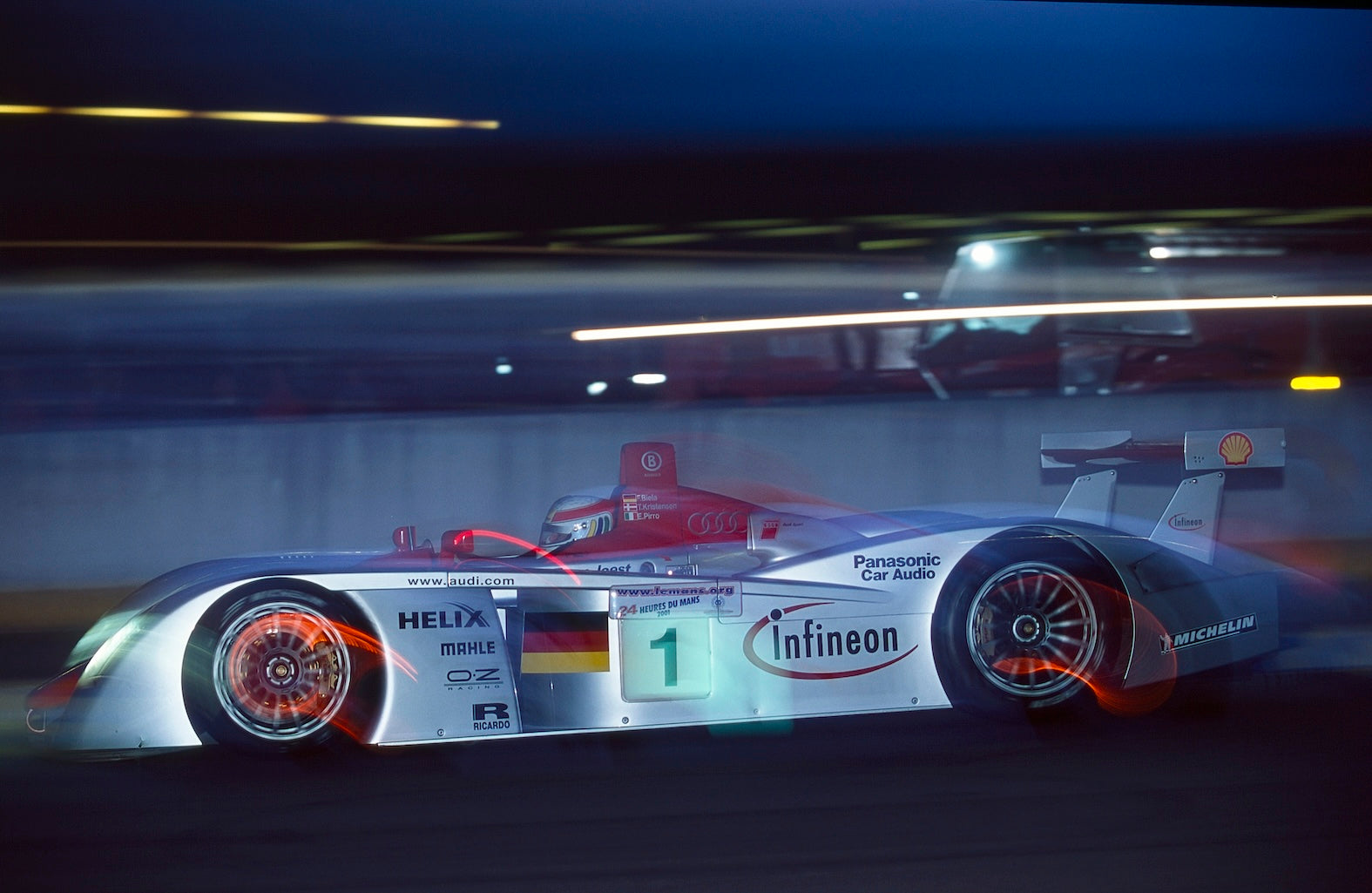

In real terms the battle for overall victory was over: it would be an Audi triumph barring catastrophe. Each of the three R8s had minor issues with punctures or having to use an escape road but their relentless pace found no answer from the opposition: they simply drove away from the field. Drawing on its extensive rallying experience, Audi Sport had anticipated potential problems and devised solutions. After the introduction of the two chicanes on Les Hunaudières there was a significant increase in the likelihood of transmission problems. Audi’s answer was to make it possible to change the entire unit quickly. Two R8s did, taking around seven or eight minutes each; the other car – driven by Biela, Tom Kristensen and Emanuele Pirro – did not, and therefore won the race.

With the rest of the LM P900 field suffering a range of misfortunes and maladies, a steady performance from the Pescarolo Sport Courage C52-Peugeot of Sébastien Bourdais, Olivier Grouillard and Emmanuel Clérico was rewarded with a fine fourth place, albeit 24 laps down on the winner, further evidence of the crushing superiority of the Audis.

The contest in the LM P675 class was a fight for survival, only two of the six competitors making it to the finish. The Multimatic Motorsport Lola B2K/40-Nissan driven by Scott Maxwell, John Graham and Greg Wilkins overcame a crash during the night to secure class victory by eight laps.

Arguably the most eagerly anticipated battle at Le Mans in 2000 played out in LM GTS between the three ORECA Vipers and the Corvette Racing pair. It was a Gran Turismo equivalent of boxing’s ‘The Rumble in the Jungle’ or ‘The Thrilla in Manila’; two American heavyweight champions chasing the title, no quarter asked or given. The pair had locked horns earlier in the year at Daytona in the Rolex 24, where their speed and reliability so wore down the prototypes that they secured the top three places outright. Just 31 seconds had been the margin of victory for the Viper over the Corvette.

The five Detroit muscle cars were united in close combat until past the halfway mark, then the greater experience of the ORECA squad, and its fully developed Viper, proved to be just enough. The Vipers took first and second in class with Olivier Beretta, Karl Wendlinger and Dominique Dupuy on the top step. In a very creditable début performance at the 24 Hours, Corvette Racing took the next two places; surely their time would come.

LM GT was a purely Porsche affair and despite the intervention of Christophe Bouchut in qualifying, the category was dominated by the Dick Barbour Racing outfit with factory-contracted drivers Bob Wollek, Lucas Luhr and Dirk Müller outpacing the rest. They had open support from Porsche Cars North America and the likes of the legendary Norbert Singer was on hand to lend assistance. However, a miscalculation in the size of the fuel tank brought exclusion, which gifted the win to Hideo Fukuyama, Atsushi Yogo and Bruno Lambert in the Team Taisan Advan 996 GT3 R.

ORGANISATION

Almost immediately after the end of the 1999 race the recriminations began, concerning the Mercedes-Benz CLRs getting airborne on three separate occasions. The FIA launched a formal inquiry into the circumstances surrounding these incidents. It soon became evident that the ACO and the circuit were the target of this initiative rather than the CLR’s design, and leaked reports from the FIA suggested some rule changes to prevent any repeat performances. The rumours also revealed that particular attention was being paid to the undulating nature of parts of the Circuit de la Sarthe. One of the more bizarre series of suggestions that emerged was the introduction of ‘no-overtaking zones’ and a mandatory flattening of bumps and other elevation changes.

A couple of months passed and the rhetoric from the FIA toned down slightly with ‘mandatory’ being changed to ‘a strong recommendation’. The ACO’s proposals for modifying the cars were also softened after discussions with the manufacturers and constructors. In March 2000, the ACO announced that it would flatten the final part of Les Hunaudières in time for the 2001 race.

The FIA considered three other specific matters in its inquiry. Why had the ACO allowed the two Mercedes to start the race after the Saturday morning incident? In the ACO’s view it was the responsibility of Mercedes-Benz to decide whether the cars were fit to compete. The time taken for the emergency personnel to attend Peter Dumbreck’s stricken Mercedes was also questioned and was attributed to communication issues. The final cause for concern was the decision to move Martin Brundle’s stationary Toyota across the track at Arnage during the race. After suffering a rear puncture on Les Hunaudières, Brundle had attempted to get the Toyota back to the pits with both rear tyres flat until eventually the gearbox casing had fractured, stranding the car in a hazardous position. The least bad option, in the opinion of the officials, had been to drag the immobile car across the road and behind the barriers into a place of relative safety, as there was only a very short escape road at the corner and no run-off area on the other side of what was public highway.

At no point did Mercedes-Benz come in for public censure or criticism from the FIA, despite the issue only affecting its cars; cynics wondered if the company’s prominent position in Formula 1 may have had some influence on this apparent silence. There was also speculation that the successful legal action launched by the ACO against the FIA after the 1992 event, for breach of contract, may have been an underlying element in this process. The final act of this unwholesome affair was the FIA sending an official observer to the 2000 Le Mans 24 Hours.

Several improvements were made to the track with a major increase in the run-off area and gravel traps at Indianapolis being the most prominent. New safety fencing was installed at the Porsche curves and the kerbs at the Ford chicane were replaced and updated. Off track, the public areas were also worked on, with the new Georges Durand grandstand, exclusively reserved for ACO members, built across from the pitlane. Most of the other tribunes and their facilities were modernised for the benefit of the fans.

Corporate structures in the paddock grew in size and complexity, following the trend started with the return of the major manufacturers in the preceding couple of years. Audi, in particular, used the hospitality element to drive its business onwards, entertaining customers and important staff.

As expected, the events of 1999 did affect the technical rules. As it was considered beneficial to slow down the cars, power was restricted by 5–10 per cent to around the 600bhp mark in the top prototype class through the use of air restrictors and reduced turbo boost. Front and rear bodywork overhang was shortened, and grilles, to allow the passage of air, were mandated above the front wheels. The minimum weight of the classes remained unchanged, with LM P900 at 900kg and LM GTS/GT at 1,110kg. An updated junior prototype class, LM P675, was reintroduced with the aim of encouraging smaller private teams and constructors to compete. As suggested by its name, the minimum weight was 675kg, and the maximum engine capacity was 3.4-litres for normally aspirated units and 2-litres for turbocharged ones.

To mark the new millennium the ACO consulted with a collection of Le Mans experts, media and aficionados. The target was to get a consensus on which races, cars and drivers best embodied the ‘Spirit of Le Mans’. An exhibition to celebrate the race was mounted by the local authorities and during this Jacky Ickx was proclaimed to be ‘Driver of the Century’. The Belgian maestro, a six-time winner at La Sarthe, was made an Honorary Citizen of Le Mans on the Friday before the race. Ickx was also the Honorary Starter, the fifth driver privileged to wave Le Tricolore to get proceedings underway.

Patrick Peter organised a supporting race, the Shell Historic Ferrari-Maserati Trophy, with no fewer than 51 classic Italians, including 40 of Maranello’s finest. Victory was claimed by David Franklin in the Ferrari 365 GTB4 that had finished fifth overall and headed the GTS class in 1972, driven by Claude Ballot-Léna and Jean-Claude Andruet.

Two long-standing servants of the race retired after the 2000 event. The ACO sports director, Jean-Pierre Moreau, had been with the club since 1967 and had held senior positions during that period, taking responsibility for much of the huge behind-the-scenes effort to make the race happen. Marcel Martin had been the clerk of the course since 1981 and only the fourth individual to hold this position.

AUDI, AUDI, AUDI!

Even as Audi celebrated a podium finish at Le Mans in 1999, an urgent list of proposals and improvements was drawn up. Only victory would be acceptable in 2000. Wolfgang Appel, Audi Sport’s head of vehicle technology, declared that there were two targets: to make the car faster and to allow easier maintenance. The distraction of running both open and closed prototypes was sorted by ending the R8C project, although it would eventually prove to be the inspiration for the Bentley Speed 8.

Audi Sport’s chief aerodynamicist, Michael Pfadenhauer, reviewed all aspects of the existing car and was supported in this task by Tony Southgate, who had been deeply involved in both the R8R and the R8C. A completely new chassis was designed with a monocoque constructed by Dallara to the minimum dimensions permitted by the ACO’s technical specifications for LM P900. A consequence of this was that taller drivers struggled to get comfortable in the confined cockpit. The radiators were relocated from the front to the side, allowing a single-seater-style raised nose with reduced frontal area. Along with a lower centre of gravity and better weight distribution, handling and straight-line speed were improved. Use of a single roll hoop rather than the double hoop of the R8R increased airflow on the rear wing and, consequently, downforce. The new position of the radiators and the narrower tub enabled the engine to be fully stressed, reducing weight and increasing chassis rigidity.

Appel took overall responsibility for chassis development. One detailed change over the R8R was mounting the rear suspension and wing on the transmission casing. Whereas in 1999 the gearbox could be changed in a little over ten minutes, the new arrangement meant that this could be done in about half that time.

One element carried over from the R8R was the engine, a 3.6-litre V8 with twin turbochargers that had performed faultlessly. There were incremental refinements and claims were made of a substantial increase in torque and an improvement in fuel efficiency. A revised exhaust system saved 12kg. Both Ricardo and Audi Sport completely reworked the transmission and pneumatic paddle-shift system, with a new magnesium alloy casing saving a further 15kg.

The new racer, designated R8, was shaken down just before Christmas at Neustadt test track. A full development programme was implemented, beginning at Vallelunga, and the car was launched to the public on Miami South Beach in the run-up to its race début at the Sebring 12 Hours, where a convincing 1–2 reinforced the message that Audi was the class of the field.

This sense of superiority continued during the preliminary practice at Le Mans with the Audi trio comfortably ahead of the opposition. Indeed, the only hiccup came when Allan McNish speared off the track at the entry to the Porsche curves during the afternoon session. An oil leak was blamed but there was little damage to the car.

Six weeks later the circus was back in town. As soon as the action got underway on Wednesday evening the timing screens were topped by Audi and that remained the position right through until midnight on Thursday.

The only shadow of doubt in the Audi camp that evening came when Christian Abt rolled to a halt while leaving the pitlane. Following much speculation, there was a press release the following morning disclosing that ‘#7 had to stop because of an engine failure’. Later it was admitted that a piston had broken, still unexplained to this day. This may have given a ray of hope to the opposition, but it was a false hope. In fact, in the 80 races in which the Audi R8 competed over six seasons, this was the only instance of engine failure. The head of engine technology, Ulrich Baretzky, and his team headed by Hartmut Diel, had produced a powerful and supremely reliable powerplant, with an output estimated to be just over 600bhp.

There were other issues behind the scenes: the universal joints of the rear wishbones were thought to be a weakness after qualifying. Back at Ingolstadt modified components were made and flown in to be fitted just before the start of the race. However, the media and the fans were none the wiser.

A vital element in the performance of the Audis was the contribution of Joest Racing, whose methodical and disciplined approach to endurance racing matched the engineering excellence displayed by Audi Sport. Reinhold Joest and Ralf Jüttner had assembled a group that knew what was expected of them and they executed their obligations almost perfectly.

The Audis led the race from start to finish except when David Brabham’s Panoz briefly headed the field at around the one-hour mark. McNish recaptured the lead and held on to it with his co-drivers Laurent Aïello and Stéphane Ortelli for the next five hours, despite Ortelli spinning the R8 as he exited Indianapolis and lightly striking the Armco. Just before 23.00 Aïello pitted and the car was dragged into the pitbox for a complete change of the rear end, including gearbox, suspension, brakes and wheels; amazingly, the whole effort took under seven minutes. Quoted at the time, Aïello said, ‘The gearbox got notchy, on my very last lap. So, we changed it as a precaution.’ The telemetry also indicated a slight decrease in pneumatic pressure on downshifts and this was enough to trigger replacement of the rear. A couple of hours later the car lost a further few minutes having the rear diffuser changed. McNish’s quadruple stint at around dawn saw him visibly faster than any other driver on track and he confirmed this observation by setting the fastest lap of the race with a time of 3:37.359 on his 233rd lap at 07.21. However, even such heroics could not make up for the time lost in the pits, and second place would be insufficient reward for such a performance.

The Audi of Rinaldo Capello, Michele Alboreto and Christian Abt assumed the lead during the enforced stop of the McNish/Aïello/Ortelli car and maintained its advantage for the next four hours. With Abt at the wheel, the car had a puncture approaching the Michelin chicane on Les Hunaudières and he just managed to avoid disaster. On the way back to the pits the rear suspension was damaged and a rear-end change was the team’s answer, demoting the car to third place where it remained to the end.

Audi’s cause was taken up by Tom Kristensen, Frank Biela and Emanuele Pirro when they slipped into the top spot in the 11th hour. The trio had maintained a steady pace in the opening stages, slightly delayed by a puncture while Kristensen was driving, but he managed to get the R8 back to the pitlane without damaging the suspension, so no change at the rear. Later, Biela had to use the escape road at the Michelin chicane, but there were no further consequences. During a series of routine pitstops the windscreen was changed twice but that was the limit of attention beyond the regular fuel and tyres, the latter triple-stinted to the end of the race.

The instruction to arrange a photo finish with the three Audi R8s was passed on to the drivers and at 16.02 Pirro, McNish and Abt crossed the finish line in formation. Audi had conquered Le Mans! It was a most emphatic victory that never looked in doubt. Considering the number of high-profile manufacturer campaigns that have turned sour at La Sarthe, Audi’s domination of the event from start to finish was astounding.

There were celebrations long into the Sunday night and Monday morning in the Audi camp, although one person was missing. McNish was back in the UK before the party was over, feeling that victory had eluded him and not in a mood to celebrate. A week or so later, a piece in Autosport speculated on this course of action and some observers questioned whether the winning car somehow had been favoured by not having its rear end changed, especially after Kristensen’s puncture. Others wondered whether having a German driving the winning car contributed to the situation. Given the level of professionalism displayed by Audi Sport at the whole event it seems somewhat unlikely that anything would have been left to chance. The only people who knew the complete situation were within the team and they were saying nothing. Whatever the answer, Audi, under the leadership of Dr Ullrich, had turned in one of most complete performances ever witnessed at La Sarthe. The opposition must have wondered whether this would become a regular display.

THE PRICE IS RIGHT

While the campaigns of American newcomers Cadillac and Chrysler caught the focus of the media, it was Don Panoz’s empire that offered the strongest challenge to Audi. In 1999 the Panoz entries had beaten BMW to the teams’ LM P title in the American Le Mans Series, scoring three victories along the way, despite their unconventional layout with the drivers sitting behind the engine. The rule changes imposed in the wake of the Mercedes debacle caused problems for Panoz’s Roadster; smaller wings, a mandatory ‘Gurney flap’ and louvres over the front wheels combined to make the car less stable. After the preliminary practice, however, various modifications – including a revised front splitter and flat-bottom profile – were tested at Spa and judged to have largely cured the issues. The preparation of the distinctive, rumbling 6-litre V8 Ford was now entrusted to the in-house outfit, Elan Power Products, an alliance between Panoz and Zytek.

Although there appeared to be three different Panoz teams, in reality the whole operation was under the management of David Price, who was a director of Panoz Motor Sports as well as David Price Racing (DPR). Price had run the Panoz programme at Le Mans and in the FIA GT Championship in 1997.

There were five examples of the Andy Thorby-designed Panoz LMP 1 Roadster S on the grid. Two were entered by Panoz Motor Sports with the first car’s regular ALMS pilots, David Brabham and Jan Magnussen, joined in France by the legendary Mario Andretti, taking a last shot at the one prize that had eluded him during his glittering career. The other ALMS driving pair, Johnny O’Connell and Hiroki Katoh, were supported by Pierre-Henri Raphanel.

A pair of Panoz flew the TV Ashai Team Dragon banner. This enterprise was an alliance between the Ashai TV channel and former entrant Kazumichi Goh, with Japanese drivers Keiichi Tsuchiya (aka ‘Dorikin’), Masahiko Kondo (a popstar) and Akira Iida. The second car featured the Kageyama brothers, Masami and Masahiko, with Toshio Suzuki. A PR release informed the media that earlier the team had flown an artist over from Japan to measure the Panoz, returned him home to create the artwork, then brought him back again to apply his work to the cars, all this amounting to a distance approaching 25,000 miles.

The fifth Panoz was entered by Team Den Blå Avis, which was also competing in the SportsRacing World Cup. The SRWC mandated that its entrants run prototypes with full roll-over bars (as opposed to the single roll-over bar configuration permitted under ACO regulations) and use Pirelli tyres. As this Panoz appeared in the preliminary practice in SRWC configuration, including slightly modified bodywork, the team was obliged by the ACO to retain this specification for the race itself. This entailed a weight penalty of around 20kg and caused disturbance of airflow to the rear wing, reducing grip. On the driving front, John Nielsen and Mauro Baldi were partnered by Panoz test driver Klaus Graff for his Le Mans début.

The Panoz squad struggled in the preliminary practice with handling problems and to many observers’ surprise the fastest of the drivers was Masami Kageyama, who just pipped Brabham for seventh place according to unofficial sources.

It was a different story during race week. Brabham was comfortably the fastest of the Panoz gang, and he was also best of the non-Audis, occupying fourth, while Katoh pushed hard on the Wednesday evening to secure eighth spot. Back another four places were the two Japanese cars, with Masami Kageyama just in front of Tsuchiya. As expected, the Danish entry was the slowest of the quintet, a further two slots back.

In the race the Brabham/Magnussen/Andretti Panoz was the only car to take the fight to Audi but even they were two laps down 10 hours into the contest. Both Audi and Panoz were getting 12 laps to a tank of fuel and their Michelins ran triple stints with ease. Andretti struggled to maintain the absolute pace of his younger rivals but was by no means outclassed. In the early hours of Sunday morning the challenge of the leading Panoz was blunted when Magnussen brought the car in for attention to the gearbox costing 20 minutes. Two hours later the car was once again in the pitbox for a transmission replacement. On the Sunday afternoon, with Andretti at the wheel, the Panoz had a front puncture and the American managed to maintain control, just glancing the barriers at Arnage. All of which conspired to send it tumbling down the order to finish 15th overall and eighth in LM P900. After such a strong performance in the first half of the race this was a disappointing result and an unsatisfactory finale to Mario Andretti’s glittering career.

The other factory Panoz of O’Connell/Katoh/Raphanel was a consistent runner in the top six for most of the race. They too had to stop twice for gearbox changes, on the second occasion also for a rear-axle swap, but the total time lost was under an hour. With the carnage that reigned in the prototype ranks, the trio were able to ease back up the order to finish fifth overall and in class.

The TV Ashai Team Dragon crews adopted different strategies in their approach to the race. Tsuchiya/Kondo/Iida ran conservatively in the opening stages but gradually ascended the leader board to reach seventh place at the nine-hour mark, when they suffered a couple of punctures causing rear-suspension damage. They also had to replace the transmission on Sunday morning but were able to cruise home after that, winding up eighth overall and seventh in class. The Kageyama/Kageyama/Suzuki Panoz ran at the pace of the second factory car in the top ten, swapping positions as one or other sustained punctures. The contest was resolved with a few hours to go when the Japanese car pitted with gear-selection issues; they resumed in sixth place, which is where they finished.

The Den Blå Avis-sponsored car of Nielsen/Baldi/Graff may have qualified only 15th but a typically assertive performance from ‘SuperJohn’ dragged the car into the top six by the third hour. Graff took over and in his second stint hit the wall at Mulsanne corner, heavily damaging the front end. The German attempted to get back to the pits but was involved in a collision at Indianapolis with the S.M.G. Courage that caused further destruction. Eventually he made it to the sanctuary of the pitlane and the car received extensive repairs over the course of the next five hours. It returned to the race after midnight only to suffer a further problem with the steering that lost another three hours. Any hope of reaching the 70% of the winner’s distance necessary for classification under ACO rules was lost and the Danish Panoz rolled across the line at the finish 52 laps short of its target.

DETROIT SPINNERS

At the Geneva Motor Show in March 1999, John Smith, CEO of Cadillac, announced a three-year programme to enter the Le Mans 24 Hours and win it outright by 2002. That target would coincide with Cadillac’s centenary, a marketeer’s dream. The marque was named after the founder of the city of Detroit, a French adventurer, Antoine de la Mothe Cadillac, and the bicentennial of the city would also fall into the period of the Le Mans campaign.

The real aim of the project was to change the image of the luxury American car manufacturer and also launch the product range globally, outside its traditional North American marketplace. In parallel, Cadillac’s US customer base was being eroded by the high-performance offerings of the likes of Audi, BMW and Mercedes-Benz, so defeating the Germans at the world’s greatest race would be one way of changing brand perception.

Riley & Scott was commissioned to lead the project, headed by Bob and Bill Riley, together with their chief designer, Carl Seaberg. The Cadillac Northstar LMP was a conventional open prototype featuring a carbon monocoque with aluminium honeycomb core. Certain Cadillac design cues were included, notably the front grille. The engine was a 4-litre twin-turbocharged, aluminium 32-valve V8, developed in partnership with McLaren Engines and IHI. The choice of a turbocharged unit was made for the better fuel economy achieved at the same power output. The engine had its origins in the IRL Oldsmobile Aurora unit but was completely reworked. The original cars were equipped with a six-speed Emco longitudinal gearbox designed to be accessible without removing the rear suspension.

The first car was rolled out in September 1999, followed by a series of private tests at Daytona and Sebring. At the car’s launch GM motorsport director Herb Fishel revealed that a customer programme was planned with up to 10 cars to made available before Le Mans 2000. The price was fixed at $650,000 (ALMS/ACO carbon brakes, single roll hoop and diffuser) or $638,000 (ISRS/GARRA steel brakes and double roll hoop) per car delivered ready to shake down and test.

The US factory team, under Bill Riley, made two entries in the 2000 Rolex 24 at Daytona. Riley hired Butch Leitzinger, Andy Wallace and Franck Lagorce for one car, and Wayne Taylor, Max Angelelli and Eric van de Poele for the other. The latter trio led the Sebring race at the six-hour point, but issues with the rear brakes and a gearbox failure put paid to any thoughts of a début victory. There was an extensive list of issues to address and a new transverse gearbox from Xtrac was on the way. At Sebring, Cadillac received a reality check when the Audi R8 broke cover and showed a combination of speed and reliability that simply overwhelmed the opposition.

Four Cadillacs – two factory entries and two from DAMS – lined up at La Sarthe. Drivers of the DAMS cars were Emmanuel Collard/Éric Bernard/Franck Montagny and Christophe Tinseau/Marc Goossens/Kristian Kolby; both Montagny and Kolby were racing in F3000 that season for DAMS. The unofficial times recorded at the preliminary practice illustrated the mountain that Cadillac had to climb, with none of the cars getting into the top ten. More concerning was the apparent lack of straight-line speed, allied to persistent understeer.

Come race week the quartet struggled on the first day of action but rallied on the Thursday, Collard pushing into ninth place, with Wallace two slots further back, while van de Poele took 16th and Tinseau was mired down in 20th. A reliable and trouble-free race would be the best hope of a good result.

Three of the Cadillacs were running with the new Xtrac transmission, essentially the same system used by Mercedes-Benz and Toyota on their GT1 projects, leaving just the Tinseau/Goossens/Kolby car using the older Emco unit. The rear suspension had also been revised after an intensive test programme and these modifications saved 16kg.

A sign of the times was the announcement that live telemetry data and in-car camera material would be available online. The factory cars were also equipped with a NightVision infrared camera (installed in the right-hand headlight) to show the driver more of the road ahead at night. This was also a marketing tie-in with a similar system being offered as an option on the road-specification Cadillac DeVille. Fog at the local airfield on the Tuesday morning of race week gave the team an opportunity to demonstrate this system to the media, which remained largely sceptical about its real value. The three safety cars were modified Cadillac STSi models.

The warm-up session early on Saturday proved to be a disaster for Kolby as he spun exiting the Ford chicane and hit the pitwall with considerable force. The mechanics worked furiously to replace the engine, transmission and rear suspension, performing an outstanding job to get the car to the grid.

Just 18 minutes into the race, Tinseau’s car went up in flames while speeding down Les Hunaudières after an oil pipe fractured. The prototype was destroyed but the driver managed to escape with only minor burns. However, this was not the message that the Cadillac top brass wanted to send to potential new customers watching the race on television.

Then van de Poele spun at the beginning of his stint while approaching the Motorola chicane, causing damage to bodywork, diffuser and rear wing that took 20 minutes to repair. An issue that had afflicted the Cadillacs since their début was overheating at the rear and this then caused a wheel to become jammed onto the axle, losing a further 40 minutes. Finally, replacement of the transmission and clutch on Sunday morning took over two hours. The car limped over the line to finish 22nd overall.

The sister car of Wallace/Leitzinger/Lagorce ran in the top ten for the first four hours, then it too struck problems with sticking wheels and clutch failure. Like its sister car it would spend the best part of five hours in the pits and just managed to make the finish one spot above the other factory car to complete a very disappointing race for the team. The other area of concern was being forced to refuel every 10 or 11 laps. If extrapolated this was the equivalent of giving their rivals a three-lap advantage, something that would need addressing to have any hope of victory in the future. There were also reports of a fuel pick-up problem that brought about premature stops as a precaution.

The other DAMS Cadillac of Collard/Bernard/Montagny climbed to fourth place at around the midway point. It appeared that this would give the Northstar outfit a decent result, but fate had other ideas. Just after midday a rear wishbone snapped while passing the pits, leaving Bernard the task of dragging the car round for almost a whole lap, which he somehow managed. The damage to the rear of the Cadillac was considerable, including one of the turbos, and the crew worked feverishly to make repairs while watching the car steadily lose places. After about an hour Montagny went out on a slow, exploratory lap but returned immediately, declaring that the car was undriveable, and there were also concerns regarding engine cooling. So, the Cadillac remained parked until just before the end of the race and then completed a final lap to ensure that it would be classified, albeit only 19th. One consolation for the DAMS team was being awarded the Escra-Iscram trophy, in its 25th year, to the technical crew led by Sebastian Frère. The Ecole Supérieure du Commerce des Réseaux de l’Automobile created the prize in partnership with the ACO to recognise the group of mechanics providing the highest level of technical assistance.

ROUGE REYNARD

Detroit was also represented in the LM P900 ranks by Chrysler. It was the 75th anniversary of Chrysler entering Le Mans back in 1925, with a Chrysler 70, the first American car to race at the 24 Hours. In March, a three-year prototype programme was announced with the aim of victory in 2002. High-profile sponsorship from PlayStation, described at the time as a partnership, suggested that Chrysler was perhaps unwilling to fund the project to the level of Audi. The plan was to approach the event as a test session, using a pair of Reynard 2KQ chassis, the work of Paul Brown and Kieron Salter of Reynard Special Projects Division. ORECA would then design and build its own race car. The race would also be a proving ground for the 6-litre V8-Mopar engine, produced by Caldwell Developments, an evolution of powerplants used in sprint car and World of Outlaws events.

After the Reynard chassis struggled at Daytona and Sebring, top-flight designer Nigel Stroud was enlisted to get the cars better suited to the challenges of Le Mans. In the preliminary practice the two Mopar Team ORECA cars were driven by Olivier Beretta and Yannick Dalmas, the latter designated as ‘Captain’ of the prototype project by team boss Hugues de Chaunac. There were several teething problems with the engine installation and mapping, this being a knock-on effect of the delays with the chassis. When the unofficial timesheets showed that both cars were just outside the top 20, a radical rethink was forced upon Chrysler. Beretta was reassigned to the Viper team and the main marketing effort was refocused on the contest with Corvette in LM GTS.

This meant that a revised set of drivers were recruited for the race itself. Joining Dalmas were Nic Minassian and Jean-Philippe Belloc, while Didier Theys led the second car with Jeffrey van Hooydonk and Didier André.

In the qualifying sessions the value provided by Dalmas was shown when he posted the 14th fastest time, with Theys eight spots behind. For Mopar Team ORECA it would be a case of trying to run without interruptions and see where they landed on Sunday afternoon.

That strategy went out of the window on the first lap when the Dalmas car’s oil pressure plummeted and it rolled to a halt at Mulsanne corner, game over. Instructions were then passed to the other crew to take things gently, as data accumulation became the priority. For 90 minutes Theys/van Hooydonk/André ran in the top 20, then the nightmare began. First, the water pump failed, followed by four gearbox changes, and there were other problems with the clutch, brakes and accelerator. Nearly four hours were spent in the pits, but the team did not give up; on the positive side the engine never missed a beat. At the chequered flag they managed to record a finish in 20th place.

A third Reynard 2KQ was entered by Johansson Matthews Racing, an alliance between Stefan Johansson and Jim Matthews. After the first batch of Reynard 2KQ tests in the USA did not go to plan, several customers abandoned plans to race the car but Johansson Matthews persevered and effectively became the development team. Their choice of engine was a 4-litre Judd GV4 V10 that was fully stressed. Johansson Matthews competed at the Rolex 24, qualifying fourth. The Reynard showed good pace, especially with Johansson or Guy Smith at the wheel, but suffered myriad new-car problems, eventually finishing 23rd. At Sebring they ran comfortably in the top ten for the first two hours, then suffered a blown engine.

The outfit regrouped and made the best of Stroud’s changes, running sixth fastest at the preliminary practice. The team had purchased a second chassis and this was the one that ran at Le Mans. Although the package was coming together, it was clear that the 24 Hours was a few months too soon. A revised Reynard/Gemini transmission was developed to cure the issues encountered so far. Johansson put in a big effort to propel the car up the grid to seventh place, the first of the Reynards. The car also topped the maximum speed table, recording 329kph down Les Hunaudières. During the traditional Friday drivers’ parade, Smith was also in the limelight, receiving the Rookie of the Year Trophy. In the race, the Reynard ran in the top ten until just before midnight, when the gearbox had to be changed, taking 12 minutes. A couple of hours later the engine failed.

THE GREEN, GREEN GRASS OF HOME

Approaching the 2000 Le Mans 24 Hours, Henri Pescarolo made the jump from behind the wheel to behind the stopwatch, as team patron. Pescarolo Sport was formed early in the year and took up residence in the Technoparc behind the circuit’s paddock. The plan was to run an ex-factory Courage C52 with the support of the various local authorities and ELF. Additionally, the team received the official backing of Peugeot Sport, which provided the engine. This was the twin-turbocharged 3.2-litre V6 Peugeot ES9 J4S, developed by SODEMO and based on the powerplant of the new Peugeot 607 road car. Drivers were Olivier Grouillard, Emmanuel Clérico and Sébastien Bourdais.

Pescarolo Sport in 2000 was in many ways the motorsport equivalent of ‘La France Profonde’, a return to traditional merits of consistency and reliability, making every centime count. It was obvious that the Courage C52 was no match for the other LM P900 competitors on pace, so a different strategy was called for. The unproven Peugeot engine performed well in testing and there was guarded optimism about its durability.

The preliminary practice seemed to confirm the team’s expectations. The package felt solid, especially the Peugeot engine, and the time was spent preparing for the race.

In front of enthusiastic local support, Clérico posted the 17th fastest time in qualifying, almost ten seconds off McNish’s pole effort. In the race the Courage was in the leading dozen for the first four hours and then slipped into the top ten as darkness approached, reaching seventh at the halfway point. The only hiccup came during the night, at 02.30, when Bourdais suffered a puncture on the run from Mulsanne corner. After he had limped to the pits, the team had trouble getting the old wheel off, and the engine cover also needed replacement due to damage. The team was also forced to use a trolley jack rather than the on-board air jacks but managed to get the car back in the race without losing a place.

The next problem encountered was a broken suspension rocker arm, but this was changed in a few minutes. Thereafter the Courage ran with no further unscheduled stops, ascending the order as others hit trouble. Reaching fourth place with just over four hours to go, the drivers ground out the laps until Marcel Martin waved the chequered flag to bring proceedings to a conclusion. The Peugeot V6 never missed a beat, and a perfect strategy was devised, and executed, by wily old fox Ricardo Divila, who engineered the car. The Courage’s triumph almost matched that of Audi.

The absence of Courage as a works team meant its personnel focused their attention on its customer teams. Besides Pescarolo Sport, S.M.G. entered a brand-new Courage C60 powered by a 4-litre Judd GV4 V10. The sleek design, the work of Paolo Catone, was driven by team owner Philippe Gache with Didier Cottaz (Courage’s official test driver) and Gary Formato, who had raced at Le Mans with Gache in 1999.

In race week, the first sessions were something of a disappointment for the team, the car spending most of the time in the pitbox while electrical gremlins and fuel-feed problems were sorted. Then Gache got on the pace and finished up sixth.

In the race Gache initially ran fifth but managed to spin in the middle of the Motorola chicane on lap three, fortunately without collecting any other cars. The C60 established itself in the top ten until after midnight, when attention to the brakes cost 20 minutes. As the sun came up a further half hour was lost repairing a water leak. Then disaster struck as Formato headed at full speed from Mulsanne corner and had a blow-out on the rear left. He received instructions over the radio as he dealt with the mangled bodywork for 35 minutes before he could attempt to get back to the pits. Almost a further two and a half hours passed while the crew repaired the carnage. Gache then ran a few laps but sensed that all was not right and came back to the pits to retire.

THREE SERIES

The BMW V12 LM of Thomas Bscher was back for a third attempt at Le Mans, with GTC Competition now responsible for its preparation. Bscher engaged Geoff Lees and Jean-Marc Gounon, who was on-loan from BMW, to do the heavy lifting, notwithstanding that Bscher was one of the leading ‘gentlemen drivers’ on the endurance scene. The approach of the small team would mirror that of the Pescarolo outfit: run a clean, tidy race, and see where that could elevate the car by the finish.

In qualifying the BMW suffered handling difficulties and it took a huge effort from Gounon to even get as high as 21st on the grid. Steady progress in the race took the car to eighth place by the seventh hour but then the transmission started to develop major problems, forcing changes of clutch, gearbox and differential in a series of time-consuming stops. The car proved almost impossible to drive, eventually pitching Gounon off the track and damaging the undertray. Once the Frenchman returned to the pits Bscher decided to withdraw because further participation seemed pointless.

ITALIAN FAST FOOD

Following its acquisition in 1997 by Irish entrepreneur Martin Birrane, Lola returned to its roots and began building endurance sportscars once more. For the 2000 season a new model was introduced, the Lola B2K/10, a development of the B98/10. The car’s designer, Peter Weston, explained that the aim of the update was to improve both aerodynamic and cooling efficiency. Many other detailed improvements were made, based on the experiences learned on the earlier car.

Konrad Motorsport acquired one of the chassis and entered Le Mans with its client, Jan Lammers, and fellow Dutchmen Peter Kox and Tom Coronel, supported by the Talkline Racing for Holland project. Powered by a 6-litre V8 Ford, the new car was prepared by Konrad in partnership with Jack Roush.

In qualifying Lammers managed tenth place and started the race running just outside the top ten, then in Coronel’s first stint a hub failure caused a rear wheel to come off at the Michelin chicane. Coronel was seen on TV leaving the Lola to retrieve the wheel but strayed too far under the ACO’s rules and the team withdrew the car before it was disqualified.

The second Lola B2K/10 was entered by Gabriele Rafanelli with headline backing from the Olive Garden restaurant chain. The team chose the 4-litre Judd GV4 V10 to power its prototype, presented in the colours of the Italian flag. The season got off to a mixed start at Sebring where the car was the fastest privateer prototype in qualifying but a power-steering failure early in the race brought retirement. Working closely with Lola, an intensive test and development programme followed, and the effort was rewarded with third place at Charlotte, the next round of the ALMS.

The team arrived at La Sarthe having to make a late change to its planned driver line-up because 1999 winner Pier-Luigi Martini had decided not to compete. Emanuele Naspetti was recruited to join Didier de Radiguès and Domenico Schiattarella. The trio lined up fifth on the grid after a typically committed lap from Schiattarella. In the race they were running in the top six until just before quarter distance when Naspetti hit the barriers hard in the Karting section. It took 30 minutes, and the use of a borrowed broomstick, to get the car going again. Once the Italian got the Lola back to the pits, a further hour was spent fixing or replacing the front and rear suspension, part of the gearbox and much of the bodywork. The final indignity came a few hours later when the engine gave up the ghost at Indianapolis.

MARI ET FEMME

Welter Racing made a welcome return to La Sarthe after a three-year absence with the husband-and-wife partnership of Rachel and Gérard Welter each entering a car. The two W.R. LMP prototypes were totally updated to comply with the latest regulations and were powered by a 2-litre in-line four-cylinder Peugeot unit. This was not a surprise given that, away from the tracks, Welter was the director of the Centre de Style de Peugeot.

While the small French team tested extensively in preparation for the 24 Hours, it did not enter any races. Frenchmen Xavier Pompidou, Jean-Bernard Bouvet and Stéphane Daoudi drove one car, while the other also had a strong Gallic element in the shape of Richard Balandras and Sylvain Boulay. The third driver was Japanese legend Yojiro Terada, who first ran at Le Mans in 1974 and would be making his 21st start in the 24 Hours.

In qualifying Pompidou put in a flyer to go third in class, whereas the other car ran at a more conservative pace. In both cases getting to the finish would be a victory. The Balandras/Boulay/Terada W.R. was the lightest car in the race, tipping the scales at 694kg during scrutineering.

Even before the race started there was a problem with the Balandras car. A hole was discovered in the radiator after the formation lap, necessitating a replacement and forcing the W.R. to start from the pitlane. Within a couple of hours, the sister car of Pompidou/Bouvet/Daoudi had to have a camshaft replaced and then suffered an oil leak. A few laps after getting back on track, Pompidou lost control in the Forest esses, clouting the barrier, and almost another hour went by repairing the damage. As dawn broke, clutch problems were encountered, and the engine began to overheat. Eventually the unit caught fire, bringing instant retirement.

The Balandras/Boulay/Terada W.R. had only minor problems during the first third of the race, but just before midnight the cooling system sprung a leak, with repair taking the best part of three hours. Several other issues and persistent overheating caused short delays but eventually the car came home 26th overall and second in LM P675, a fine reward for the team’s mechanics, who had each put in an exceptionally long shift at the coalface.

LAST DEB AT THE BALL

Another French regular in the junior prototype classes was Didier Bonnet, who decided to construct his own cars, known as Debora, an acronym of Didier Bonnet Racing. For 2000 Bonnet produced a new car, the Debora LMP2000, which was the work of Roger Rimmer. It featured a new Hewland sequential gearbox and power came from a 3.2-litre Heini Mader-tuned straight-six BMW. It was the sole car to use Avon tyres.

The all-French driver line-up was led by Patrick Lemarié (test driver at BAR Formula 1) with Yann Goudy and Jean-François Yvon joining him. The trio struggled in practice and qualifying, even Lemarié unable to achieve the necessary minimum qualifying time. The stewards deliberated after the session and showed the small outfit some mercy, allowing them to start the race. The compassion may have been misplaced as the Debora stopped out on track with engine failure after just two hours, leaving the driver, Yvon, a short walk to his home just off Les Hunaudières.

ROC AND A HARD PLACE

The third French team to enter the LM P675 class was ROC (Racing Organization Course) whose team principal, Fred Stadler, had a long history at Le Mans, including participating as a driver on three occasions as well as being an entrant over many years. In 1982 the team formed an alliance with Audi, winning several touring car championships in France and Germany. This association led to an opportunity to use a 2-litre in-line four-cylinder engine developed by Volkswagen for rallying. Homologation issues meant that it was surplus to requirements but had the potential to be competitive in the junior prototype category. VW France supported the project and the tuner, Lehmann Motoren Technik. Two Reynard 2KQ chassis were acquired and the team collaborated with the constructor to save weight, with some success, coming in at over 170kg lighter than the ORECA Reynards. A test programme at Monza and Magny-Cours racked up over 5,000km.

A strong squad of drivers was assembled, led by Ralf Kelleners with Jean-Denis Delétraz and David Terrien in one car and Jean-Christophe Boullion, Jordi Gené and Jérôme Policand in the other. The team’s potential was confirmed in qualifying when the two ROC cars set almost identical times, some six seconds up on the next LM P675 competitor. In the race the ROC Reynards ran at the head of the class for the first 90 minutes, then problems arose, and both were out before quarter distance with engine failure.

AUTOMATIC MULTIMATIC

The Lola B2K/40 was really aimed at the SR2 class in Grand-Am and SRWC, a much bigger potential for sales, rather than the LM P675 ACO rules. Adam Airey headed the team at Lola to design the aluminium honeycomb monocoque that was produced by Multimatic, a major Canadian supplier to the worldwide automobile industry.

Multimatic’s head of special vehicle operations, Larry Holt, also ran the motorsport side of the business, and it was a logical extension to create a team and prove the car at Le Mans. Power was courtesy of a 3-litre V6 Nissan engine prepared by AER (Advanced Engine Research), which proved to be no match for the turbocharged VW units over one lap but was considered a more reliable option for a long-distance event.

Ian Dawson led the team at La Sarthe, with Canadian drivers Scott Maxwell, John Graham and Greg Wilkens. Only a week after its completion, the Multimatic Motorsport Lola ran for the first time at the preliminary practice and outpaced the Debora and one of the W.R.s, making it into the race comfortably.

The car maintained its position in qualifying, setting fourth best time in class. The team opted to run a steady pace in the race rather than attack and this policy paid off as others hit problems, with the car assuming the class lead before the fourth hour. It maintained this advantage until, as night fell, Maxwell went off the road and hit the barriers approaching Arnage, damaging the rear. The best part of three hours was spent repairing the car and changing elements within the transmission, but things ran to plan once back in the contest. As the W.R. pair struck further trouble, the Lola retook the class lead before halfway and stayed there to the chequered flag, finishing eight laps up on the surviving W.R., the only other finisher in LM P675. This class victory at Le Mans was the first for Lola since 1981.

SNAKE BITE

Paul Belmondo Racing had competed in the FIA GT Championship during 1999 and was the only team to beat the ORECA Vipers, snatching victory at Homestead. It entered one of its Vipers for the team’s in-house professional, Boris Derichebourg, along with Guy Martinolle and Jean-Claude Lagniez, who had first competed at La Sarthe back in 1970 and was a top stuntman, having led the team behind the legendary car chases in the recently released thriller Ronin.

As Derichebourg was hampered by faulty shock absorbers in qualifying, the team opted to spend the second evening optimising race set-up rather than attempt to set a better time, lining up seventh. Lagniez collided with a Porsche in the first stint, which upset a connection in the engine-management system and prevented the engine from revving above 3,000rpm. Changing the black box took half an hour, dropping the Viper to the rear of the field. Further electrical problems occurred around midnight and the car’s race ended with engine failure just after dawn.

There was a Viper entered under the banner of Team Goh, which had received an automatic invitation for taking a LM GTS class win at the previous year’s Fuji 1,000Km. Team Goh focused on its Panoz pair and left Chamberlain Engineering to run the Viper with Walter Brun, Toni Seiler and Christian Gläsel behind the wheel. Seiler ended up fastest of the privateer Vipers in qualifying. The trio had a steady run until the car’s electronic system malfunctioned and an hour was lost trying to fix this. On Sunday morning Brun had the left-rear tyre fail while approaching Indianapolis, pitching the Viper into the barriers. The Swiss emerged unscathed but the car was wrecked.

The third privateer Viper was that of Carsport Holland, the team formed by Toine Hezemans, twice a Le Mans class winner, to further the motorsport career of his son. Mike Hezemans, who shared with David Hart and Hans Hugenholtz, was actually a third-generation competitor at La Sarthe as his grandfather, Mathieu, had raced a Porsche F550 in the 1956 event. Carsport acquired the chassis early in 2000 and scored a win at the Monza 500km. The team had some minor electrical issues during qualifying, including a defective alternator, but concentrated its efforts on preparing for the marathon ahead. This Viper’s race was largely uneventful, leading the privateers as rivals encountered problems. Late on Sunday morning, the best part of an hour was spent replacing the transmission, but that was the extent of the woes, and the car rolled across the line sixth in class and 13th overall.

THE LONG GOODBYE

The last two cars on the LM GTS grid were examples of the Porsche 993 GT2 R, a workhorse that had graced the Circuit de la Sarthe since 1995 but was now outdated. Freisinger Motorsport, still campaigning the Porsche in the FIA GT Championship, set the pace in qualifying, with Wolfgang Kaufmann bettering his Japanese co-drivers, Yukihiro Hane and Katsunori Iketani, to shade all three privateer Chryslers. The team’s only realistic race strategy was to aim for perfect reliability and hope for trouble to strike their opponents. That is how it played out and the trio gradually ascended into the top 20 until their car suffered two rear punctures on Sunday morning. These incidents, and a trip across the gravel at the Dunlop chicane, probably contributed to the rear-suspension collapse that caused a rear wheel to fold under the car. This calamity occurred just 11 minutes before the end of the race, so the team was unclassified.

Konrad Motorsport entered the other Porsche 993 GT2 R. Team boss Franz Konrad decided to step back from driving duties, leaving Jürgen von Gartzen as lead driver partnered by two Americans, Charles Slater and Tommy Kendall. Slowest qualifier in class, the team aimed to execute a similar strategy to the Freisinger outfit and carried out that plan to good effect, with a puncture, two bonnet changes and a trip into the gravel the only deviations. Fourteenth overall and seventh in class was a fine way for the final air-cooled Porsche to say au revoir to Le Mans.

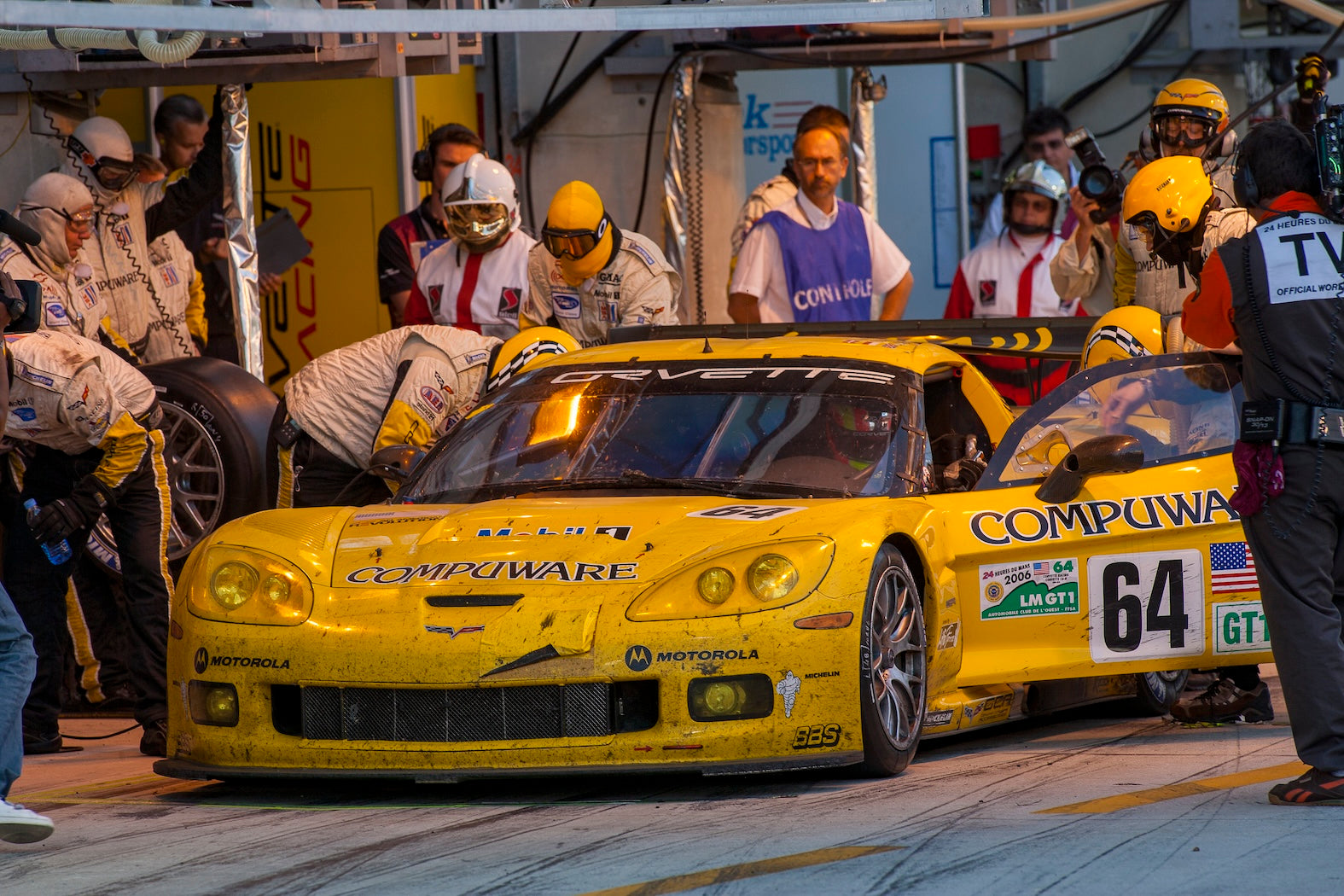

BIG YELLOW TAXI

General Motors’ decision to race the Corvette at Le Mans in 2000 had the historians reaching into their archives. As with Cadillac, it was Briggs Cunningham who introduced the American icon to the charms of La Sarthe in 1960, bringing three Corvettes with him and encouraging Lloyd ‘Lucky’ Casner to enter another one. After an eventful race, the reward for the Americans was a class win for John Fitch and Bob Grossman. From this promising beginning several other Corvette projects followed, most notably those of Georges Filipinetti and Henri Greder, the latter also taking class honours in 1973. Further attempts were made, including another class win that fell to Dick Heinz and Robert Johnson the race before Greder’s win, but most of the projects ended in failure, the last being a ZR1 in 1995.

This past record was in complete contrast to the highly professional Corvette Racing set-up, which débuted encouragingly at the 1999 Rolex 24. The team’s first season was a learning curve but for 2000 it was ready to challenge the Vipers for supremacy and entered two C5-R racers at Le Mans. The regular pairings of Ron Fellows/Chris Kneifel and Andy Pilgrim/Kelly Collins were each supported by a driver with a solid Le Mans pedigree, Justin Bell for the former pair, Franck Fréon for the latter.

The C5-R had gone through a programme of updates and improvements based around the experience of running the car in races and tests. Arguably the most important of these developments came with the introduction of a brand-new 7-litre V8 for the last rounds of the 1999 ALMS, replacing the original 6-litre unit. Mirroring the fuel-efficiency work performed at Viper, the GM Race Engine group, led by John Rice, attacked this issue in partnership with Katech’s Kevin Pranger and, as a result, was confident about getting 12 laps from a tankful. Pratt & Miller had been retained to engineer and run the Corvettes and also embarked on a similar upgrade programme, working in association with GM design engineer Ken Brown. Major changes included relocation of suspension pick-up points to provide a wider track and the introduction of a new carbon-fibre anti-roll bar. These actions saved weight and improved handling, and were supported by numerous small changes to the aerodynamics.

The Corvette Racing gang showed up for scrutineering in a light-hearted mood, the whole crew wearing cowboy hats during the obligatory photoshoot. Later, after a pre-arranged signal, they exchanged their American headgear for blue berets and a few even attached Gallic-style moustaches.

The serious business on track started and Fellows fired in a quick lap to put GM at the top of the time sheets for the first session. Wendlinger restored the Viper hegemony after the break with the fastest-ever Viper lap at Le Mans, but the fight was truly on.

Corvette Racing approached its début at Le Mans differently from all the other factory-backed teams. On its first visit the team requested the ACO’s consent to throw a reception, not for the usual VIPs but for ordinary people who worked at the event and without whom nothing would happen. This novel concept was not a huge success the first time but, as word got round, the following years were sell-outs, Les Manceaux appreciating the team’s gesture. Liberté, égalité, fraternité indeed.

When the race got underway it was clear that the Vipers and Corvettes were evenly matched, with such advantages that the ORECA-run cars enjoyed stemming from marginally better fuel consumption and tyre performance, while perhaps the biggest gain came from the years of experience accumulated at the 24 Hours.

The Corvettes kept the Vipers honest by putting them under pressure but were the first to blink when the Pilgrim/Collins/Fréon car had to have its starter motor replaced at around the halfway mark. At much same time the other Corvette had its flat bottom replaced, losing ground. At dawn Fellows got the hammer down and recorded the fastest lap, the only sub-four-minute time of the race for the class.

Despite these delays Corvette Racing ran down the clock to finish 10th and 11th overall, and third and fourth in LM GTS. It was a very impressive début performance.

NEST OF VIPERS

In LM GTS the undisputed champion was the ORECA Chrysler Viper team, having swept all before it since 1997. ORECA was looking for a third straight win at Le Mans in what was thought to be the programme’s final season, at least as a factory initiative.

Final year or not, improvements were introduced by the Chrysler Motorsport team, headed by Dick Winkles and lead design engineer Tom Wierzchon. One objective was to reduce drag and increase front downforce by changes to the splitter. The suspension and anti-roll bar were modified to improve handling and driveability. The fuel pick-up system was heavily revised to ensure that the car could maximise its fuel load. Caldwell Developments refined the mapping of the 8-litre V10, matching the mandatory air restrictors to the engine, optimising fuel consumption.

The season had got off to the best possible start with outright victory in the Rolex 24 at Daytona, followed by class wins at Sebring and Charlotte. Three entries for Le Mans were led by the 1999 winners, Olivier Beretta, Karl Wendlinger and Dominique Dupuy, who had delivered the triumph in Florida. The second entry had three ORECA regulars, Tommy Archer, Marc Duez and Patrick Huisman, on driving duties, while David Donohue, Ni Amorin and Anthony Beltoise staffed the third car.

When the first session during race week saw Corvette Racing’s Ron Fellows throw down the gauntlet by topping the timesheets, ORECA quickly responded with Wendlinger powering round to set the fastest time ever recorded by a LM GTS competitor. When the smoke cleared the order was Viper-Corvette-Corvette-Viper-Viper. The fight was well and truly on.

From the start of the race this contest continued but the efforts expended on improving the Vipers’ fuel economy paid dividends because they could run 13 or 14 laps on a tank, one or two more than the Corvettes. This advantage was nullified to some degree in the opening stages of the race with several lengthy safety-car interventions and the top five remained locked in combat on the same lap, but the Vipers gradually got the upper hand. Tyres played their part with Michelin’s much greater experience at Le Mans also helping to give the Vipers an edge over the Goodyear-shod Corvettes. Such small margins made the difference between the two contenders.

Beretta/Wendlinger/Dupuy won LM GTS after an almost trouble-free run to seventh overall, five laps ahead of the Donohue/Amorin/Beltoise car, which experienced brief delay after Amorin collided with a Porsche early on Sunday morning but nonetheless finished second in class and ninth overall. After the Archer/Duez/Huisman Viper suffered a broken rocker arm, the relevant cylinder was disconnected and they ran the final six hours of the race with reduced power to come home fifth in class and 12th overall. The victorious trio had managed to record eight more laps than their score in the previous year’s race, solid evidence of the titanic struggle waged between the two Detroit giants.

THE DIRTY DOZEN

The LM GT class was, in effect, the Porsche Supercup on steroids, as all 12 entries were Porsche 996 GT3 Rs. The racer was based on the 996 GT3 road car, which had a different engine from the rest of the 996 range. It was a 3.6-litre non-turbocharged unit that was descended from the powerplant of the 911 GT1 98, a proven Le Mans winner. The transmission also differed from the 996 road car, being an evolution of that used in the 993 GT2.

To most observers the red-hot favourite was the Dick Barbour Racing example, which was, in effect, a semi-works entry. The programme in the ALMS was supported by Porsche Cars North America and the supervising presence of legendary Porsche engineer Norbert Singer confirmed this theory. The three drivers were all under contract to Porsche Motorsport and were led by another legend, Bob Wollek, who was making his 30th appearance at La Sarthe, along with Dirk Müller and Lucas Luhr.

In qualifying, the team was surprisingly pipped by 0.296s by Larbre Compétition. In the race, though, the Barbour car just motored away from the opposition with a few quick adjustments to the dampers the only addition to the fuel/tyres/driver-change routine at their pitstops; only the race-winning Audi spent less time in the pitlane. The car won the class by a convincing nine laps and finished 13th overall. An unlucky number for some, 12 days later came the bombshell: the winner had been disqualified for having an oversized fuel tank, or, in ACO-speak, ‘withdrawn for not complying with the rules concerning the fuel capacity of the car’. How this disaster had occurred was not clear but the team manager, Tony Dowe, resigned immediately. Stories of the fuel tank expanding in the heat leaked out but why had that not happened to other 996 GT3 R competitors? As usual, Paul Frère, outright winner of the race in 1960 and undisputed doyen of the endurance media mob, had a possible answer. He postulated that the Dick Barbour Racing Porsche was the only LM GT subjected to post-race scrutineering – so was the enlarged fuel cell a one-off or was the problem more widespread?

Further evidence of the renaissance of endurance racing in North America came in the shape of two other competitors from the ALMS grid. Michael Colucci Racing entered a 996 GT3 R for owner Bob Mazzuoccola supported by Shane Lewis and Cort Wagner; the latter qualified the Porsche in fourth spot. Lewis led the class initially and then ran second, but lost control in the second hour on dropped oil in the Porsche curves, thought to be from the expiring Debora. The Porsche hit the barriers with sufficient force to concuss the driver and was eliminated.

The ALMS was also home for Australian corporate lawyer Rohan Skea’s team, which normally ran two cars and entered one of them at Le Mans. Led by veteran team manager Dave Prewitt, this effort was widely regarded as a dark horse for class victory, and a sign of the team’s status was that the third driver to join regulars Johnny Mowlem and David Murry at La Sarthe was Porsche Motorsport’s Sascha Maassen. After the car suffered a broken driveshaft early in the Wednesday session, absorbing precious track time, the team focused on the race rather than grid position. After Murry hit the wall in the Karting section 90 minutes into the race, fixing the crumpled rear end took 20 minutes, dropping the car to last place in LM GT. The trio pulled themselves together and rattled off a series of fast stints, gaining 15 places by half-distance. Other than a trip apiece into the gravel for Maassen and Mowlem, little disturbed their progress and by the finish they had risen to 18th overall and the final LM GT podium place. This was followed by a further promotion at Barbour’s expense once the officials had done their duty.

Manthey Racing’s place was taken by Floridian Porsche specialist Kevin Jeannette, who had run his team, Gunnar Racing, in the Rolex 24 with Paul Newman as one of the drivers, but plans for the movie star to reappear at Le Mans were thwarted by his convalescence from an operation. Jeannette’s son, Gunnar, was the youngest driver in the race, just turned 18, and the second youngest ever to contest the event, after Ricardo Rodríguez back in 1959. His co-drivers were Michael Brockman and Michael Lauer. Jeannette claimed the penultimate spot on the grid. The first half of the race passed without major problems but on Sunday morning a water leak was discovered and dealt with. After a few more stints, however, it became clear that this issue was potentially terminal, so the Porsche was parked for over two hours, creeping out to complete one final lap to claim 27th overall and sixth in class.

The French effort was led by previous class winner Larbre Compétition. For 2000 the team acquired a 996 GT3 R and entered it in the FIA GT Championship, winning the N-GT class at Valencia, Estoril and Silverstone. Leading the team was Christophe Bouchut with regular partner Patrice Goueslard, and the third driver was Jean-Luc Chéreau. On Thursday evening Bouchut was the talk of the pitlane when he shaded Barbour for class pole. In the opening laps of the race Bouchut maintained his lead but in the fourth hour Goueslard came out of the Forest esses to find Angelo Zadra’s Porsche stationary in the middle of the track and was unable to avoid a massive collision. Both drivers mercifully escaped unhurt, but their cars were write-offs.

The 996 GT3 R that Zadra had been driving was entered by Noël del Bello under the name of driver Jean-Luc Maury-Laribière. Joining him and the unfortunate Italian was Bernard Chauvin. This Porsche followed in the tradition of ‘art cars’ competing at Le Mans with distinctive livery by Filip O. Filipovitch.

Perspective Racing’s team principal, Thierry Perrier, was partnered by his old friend Jean-Louis Ricci and qualified eighth. Suffering from cancer and expecting this to be his last Le Mans, Ricci fulfilled an ambition to take part with his son Romano. All went to plan until just after midnight when a faulty shock absorber caused Ricci junior to spear off the track and hit the wall, but the car was able to continue after 40 minutes lost. As dawn broke, a driveshaft failure cost a further 50 minutes. Once back on track, Perrier was hit by Amorin’s Viper, but the consequences were worse for the American car. The three musketeers reached the finish in 23rd spot and fourth in class.

Racing Engineering was Spain’s sole representative at Le Mans. Team boss Alfonso de Orleans-Borbón acquired a Porsche and hired former driving partner Tomás Saldaña to lead the squad with Jesús Díez Villarroel. Completing the line-up was ex-F1 driver Giovanni Lavaggi.

The team qualified seventh and had several moments of tension before the start, having to quickly replace the windscreen after it had somehow got broken when driver changes were being practised. The car ran in the middle of the LM GT pack for the first few hours, then Lavaggi had two incidents. The second, at the Karting section, was more serious, and the radiator and various bodywork panels had to be replaced, taking over 90 minutes. The engine also sustained damage and after a couple of slow, exploratory laps, with temperatures in the red zone, the team withdrew the car.

The Porsche of Renstal Excelsior was the first all-Belgian entry at Le Mans since 1978. Two of the drivers, Kurt Dujardyn and Rudi Penders, were racing at La Sarthe for the first time, although the third driver, Philip Verellen, had competed in a Venturi in 1993. The car qualified tenth and the crew opted for the safety-first approach, which paid dividends as others fell by the wayside. They hit the top half of the class as nightfall approached, although a broken windscreen made driving in the dark more difficult. Early on Sunday morning they encountered the first of a series of problems with a burst water hose. Next up were exhaust and silencer issues, followed by a broken driveshaft. Further maladies with the engine were diagnosed and the Porsche crept around at a reduced pace for a couple of hours. The crew were happy to see the chequered flag before the engine expired, their labours rewarded with fifth place in class and 24th overall.

Swiss-based Haberthur Racing’s season had got off to the best possible start with the team’s 996 GT3 R taking the GTU class victory at the Rolex 24. Two of the drivers in that winning team, Gabrio Rosa and Fabio Babini, were back for a Le Mans début, joined by Michel Ligonnet. Babini posted the fifth fastest time in qualifying and by the fourth hour they had climbed to third place. Like the rest of the class, they were unable to live with the pace of the Barbour car but as the night wore on a podium seemed a distinct possibility. Heading into the final hour Babini slipped ahead of the pit-bound Team Taisan car for second place but with half an hour remaining the windscreen shattered. A quick stop to clear this up turned into a disaster when Babini exited the pitlane. The Porsche’s bonnet had not been secured and it flew up to completely obstruct his view. Babini continued around a very slow lap, having to lean through his opened door to see where he was going. The delay enabled the rival Taisan Porsche to make up ground but as it overtook entering the Ford chicane contact was made and both cars ended up having to escape from the gravel. The final indignity for Babini was the collapse of the left-rear wheel at Mulsanne corner in the closing minutes of the race. The car could go no further.

Seikel Motorsport’s driver line-up was led by Michel Neugarten and Max Cohen-Olivar, who would be making his 19th start, whereas the third member of the crew, Tony Burgess, was a newcomer. Neugarten grabbed third place during qualifying, completely outpacing his co-drivers. Their race largely went to plan with the only problems encountered being a trip into the gravel apiece for Cohen-Olivar and Burgess. They ended up a comfortable fourth in LM GT and 19th overall, which became a class podium a week later.